Great Depression

Although Henry Ford had been a hero to Detroit’s Black community for employing Black workers in skilled positions, the Great Depression marked a serious turning point in Black Detroit’s relationship to Henry Ford and started Black Detroiters on new courses to achieve equality. As the city’s most industrial city, the depression was experienced especially hard in Detroit. From 1929-1931, more than 200,000 Detroiters lost their jobs. No one was immune from the depression related cutbacks as teachers, factory workers, lawyers, engineers, mechanics, journalists, and even lawyers stood together in breadlines. By 1931, public relief was the sole source of income for over 210,000 people, more than half of whom were Black. A year later, thousands of these people were cut from relief rolls as the city sought ways to deal with its steadily increasing debt of $278 million. As increasing numbers of people went without jobs and relief, Detroit’s public works department received more than seven thousand calls per day about evictions.

Because Henry Ford and Ford Motor Company had been seen as benevolent, unemployed workers turned to him for help and then turned on him. Although he laid off workers during the early years of the depression, he also proposed raises and promised to not cut wages. Building on these promises, Ford declared that despite the depression, No For worker will starve.” Edsel Ford, Henry Ford’s son was on record saying, “If any unemployed Ford worker needs relief, he knows where to get it.” These statements held weight because, unlike most corporations where a long managerial chain of command makes it difficult to understand who makes decisions, Henry Ford himself was the face of Ford Motor Company and workers felt like they actually knew him.

To test Ford’s sincerity, unemployed workers in Detroit organized the Ford Hunger March in 1932. In response to layoffs, cuts to government relief, breadlines, and evictions, 3,000-5,000 people marched from Detroit to the River Rouge employment office on March 7, 1932. Made up of Black and white workers, marches carried signs demanding an end to discrimination against Black workers, end of the deadly assembly line speed-up, the use of war funds from the government for relief rolls, and jobs for laid-off workers. Led by a mixture of communists and non-communists, the leadership of the march pled with marchers to be nonviolent.

Following the leadership’s orders, when the nonviolent march crossed the line from Detroit into Dearborn where the Rouge employment office was located, Dearborn police ordered them to stop. Continuing to march, the police then threw tear gas at the peaceful demonstrators. As the march approached the gates of the hiring center, police threw more tear gas and sprayed them with icy water. Tired of this treatment, marches began throwing stones at police and Ford security. Ford security and police then began shooting at marchers, killing two and injuring another twenty-two. Two more demonstrators were killed later in the day as the battle ensued.

Ford’s choice to kill nonviolent marchers turned him from a hero into an adversary and politicized Blacks in new ways. In the wake of the Ford Hunger March Black Detroiters organized against evictions and police brutality. In October, Black postal workers created the Federation of Negro Labor. In addition to these activities, increasing numbers of Black Detroiters began to join Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, the Nation of Islam, and the Communist Party. Many also became interested in labor unions. Black Detroiters also increasingly took an active role in the Democratic Party and formed new organizations like the Civil Rights Commission.

Black Detroiters increasing openness to the Communist Party stemmed partially from the organization of unemployed councils by the Party and by their role in the case of the Scottsboro Boys. Although the Communist Party had tried for many years to spread a vision of Black and white workers fighting together on equal terms against employers, only after the massive unemployment increase of the Depression did they make inroads. In March 1930 they held a demonstration for the unemployed attended by thousands, which, within the year resulted in the creation of fifteen unemployed councils in Detroit. The growth of an interracial movement was strengthened by the Party’s promotion and defense of nine young Black men who were accused of raping two white women on a train in Scottsboro, Alabama. Since white Party members exhibited a sincere commitment to the rights of the “Scottsboro Boys” as well as their Black co-workers, the Party’s commitment to the case earned them new Black members. For those who did not join the Communist Party, the role of the Party in the Scottsboro case opened their minds to new methods of struggling for equality.

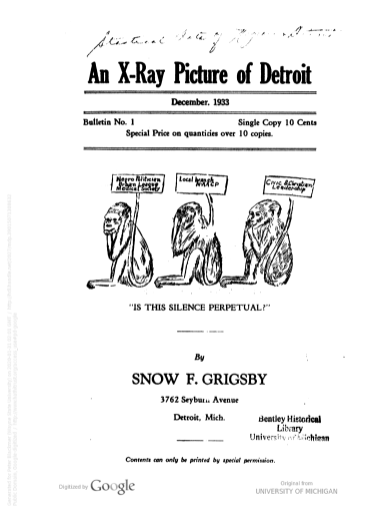

One of the most visible of these new methods was the Detroit Civil Rights Commission. Formed as a working class alternative to the NAACP in 1933 by Snow Grigsby, the CRC was initially devoted to securing jobs for Black people in municipal jobs but expanded later to cover all jobs. Also engaged in political education, the CRC produced a ten-page pamphlet called An X-ray Picture of Detroit analyzing the activism of Black organizations. Distributing the pamphlet on doorsteps, porches and church pews, it was widely read and even used in Sunday school classes. Grigsby, the author of the pamphlet, accused the NAACP of being lazy and challenged them to become more militant so that they might gain the support of the Black working classes. The CRC also organized a successful campaign to get Black workers hired at Detroit Edison, the municipal electric company.

Beth Bates, The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2012

Matthew Birkhold, “Doing for Our Time What Marx Did for His: The Boggsian Challenge to Marxist Praxis,” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2011

In this oral history interview from 1990, UAW Local 600 co-founder Dave Moore describes the impacts of the Great Depression in Detroit. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A large group of unemployed people line up in downtown Detroit near City Hall during the Great Depression. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

In this oral history interview from 1991, UAW Local 600 co-founder Dave Moore describes the Ford Hunger March in 1932. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Coffins holding the bodies of Joe York, George Bussell, Coleman Leny, and Joe Blasio, four of the men killed during the Ford Hunger March, are given a public viewing at Detroit’s Communist Party headquarters prior to their internment at Woodmere Cemetery. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

In this oral history interview frin 1990, former UAW Local 600 leader Shelton Tappes discusses the work of Unemployed Councils and the Communist Party in Detroit during the Great Depression. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Titled “An X-Ray Vision of Detroit,” this pamphlet was published by Detroit Civil Rights Commission founder Snow Grigsby in 1933. –Credit: Hathitrust

Explore The Archives

Clip from a 2018 interview with Charles Ezra Ferrell, in which he discusses the Great Depression in Detroit and the Ford Hunger March. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Demonstrators fill the streets en route to the Ford Motor Company River Rouge Plant on March 7, 1932 during the Ford Hunger March. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Transcript of an oral history interview with Detroit labor organizer Joseph Billups, conducted by Herbert Hill, Shelton Tappes, and Roberta McBride on October 27, 1967. In this interview, Billups discusses his experienecs in the IWW and Autoworkers Union, the International Labor Defense, life in Detroit, and being Black in the Communist Party. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Transcript of an oral history interview with labor leader Snow Grigsby, conducted by Roberta McBride on March 12, 1967. In this interview, Grigsby discusses race relations in Detroit following World War I, the Detroit Civic League, and jobs that opened up for Blacks after World War I. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Transcript of an oral history interview with civil rights activist Rev. Charles Hill, conducted by Roberta McBride on May 8, 1967. In this interview, Rev. Hill discusses the Ford Motor Company’s relations with the Black community, organizing at Ford, Blacks and unions, expansion of housing opportunities for Blacks in Detroit, and the 1943 Race Riot. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

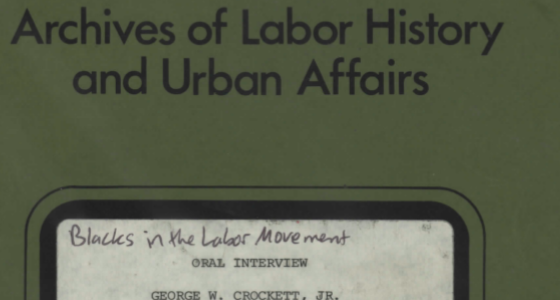

Transcript of an oral history interview with attorney and eventual Congressman George Crockett, Jr., conducted by Roberta McBride on March 2, 1968. In this interview, Crockett discusses his time in Detroit Recroder’s Court, his youth and education, activities as an attorney for the FEPC, and experiences as the UAW’s Fair Practice Committee executive director, as well as Black politics in Detroit. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

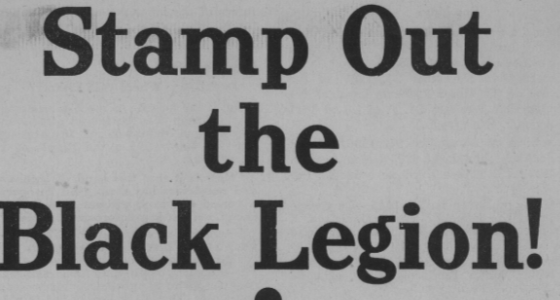

A pamphlet distributed in 1935 by the Farmer-Labor Party of Wayne County documenting the violent actions of the Black Legion. An offshoot of the Ku Klux Klan, the Black Legion terroized unionists, socialists, Jewish communities, and African Americans all over the Midwest during the Great Depression era. The Black Legion had a strong presence around Detroit where they attacked the burgeoning labor movement and enforced racial segregation. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

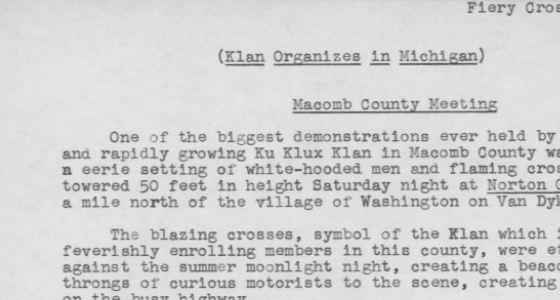

Report of meetings and recruiting strategies of the Ku Klux Klan in Macomb County and Warren Township, MI in the fall of 1940. One of the largest Klu Klux Klan chapters in the United States was headquartered in Detroit. During the Great Depression, several branches formed outside the city in Macomb and Oakland Counties, where they enforced the extreme racial segregation between the suburbs and the city. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

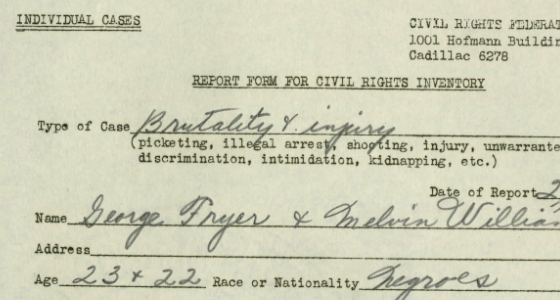

This police brutality report made by George Fryer and Melvin Williams, two young Black men, details a common instance of police brutality that Detroit civil rights groups organized around in the late 1930s. While escorting two young women near Northern High School, the Fryer and Williams were stopped and questioned by several police officers who were nearby. The officers then proceeded to attack the two men, later charging Fryer with being “drunk,” a charge he was later found not guility of. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

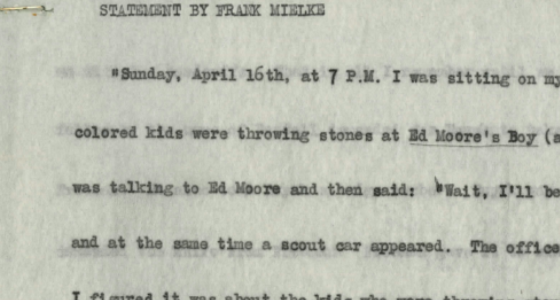

This statement by Detroit resident Frank Mielke on April 20, 1939 describes how normal, day to day activities could quickly turn into a case of police brutality when officers begin to harrase and brutalize Black residents. In this case, several police officers questioned a Black neighbor of Mielke’s about a group of Black kids playing, which then swiftly spiraled into he and his neighbors being arrested. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

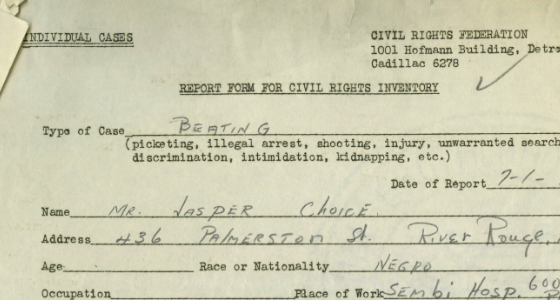

A complaint of police brutality made by Mr. Jasper Choice to the Civil Rights Federation on July 1, 1939. Police officers arrested Mr. Choice on his way home from walking a friend to the street car line. After being held overnight in a cell, offiers beat and kicked Mr. Choice, leaving him with a broken jaw.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

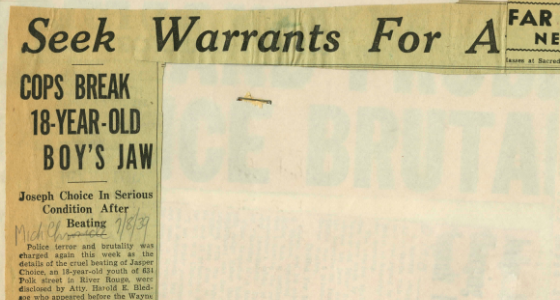

A July 8, 1939 article from the Michigan Chronicle on the police beating of 18-year-old Jasper Choice. Police officers arrested Mr. Choice on his way home from walking a friend to the street car line. After being held overnight in a cell, offiers beat and kicked Mr. Choice, leaving him with a broken jaw. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.