Political Empowerment

From 1915-1935, Black Detroit underwent a tremendous political transformation. Migrating to Detroit with hopes of a job at Ford, until the 1930s Black Detroit followed the political leadership of Henry Ford and pastors Ford was friendly with. However, after Black Detroiters experienced Henry Ford’s inhumane response to the Great Depression, they began to chart a course of political empowerment vastly different from the anti-union Republican politics of Ford.

Black Detroiters’ path towards political empowerment began when they broke with the Republican Party and began exploring options with the Democratic Party in the 1930s. At the beginning of the Depression, Frank Murphy, a Democratic judge who declared a mistrial in the cases of the Ossian Sweet defendants, ran for mayor in a 1930 special election and was elected largely from the votes of Catholic immigrants and Black migrants.

Although Ford started a rumor that Black workers would lose their jobs if the Black vote elected Murphy to a full term in 1931, Black Detroiters played an enormous role in his 1931 campaign. Beulah Young formed Murphy for Mayor clubs and penned articles in favor of Murphy in the Detroit Independent. Black pastors allowed Murphy to speak at churches and thousands of Black Detroiters showed up to hear his campaign speech at Second Baptist Church. A band formed by Black sanitation workers volunteered to play for several of Murphy’s campaign events.

After Murphy won 55 percent of the primary he faced off with Harold Emmons, Ford’s candidate for mayor. While Emmons had the backing of the city’s Republican elite and the Ku Klux Klan, Murphy won 66 percent of the vote and was re-elected to a full-term as mayor of Detroit. Murphy gave two cabinet positions to Black Detroiters in exchange for their services to him. John C. Dancy was appointed to the House of Correction Commission and Rev. Robert Bradby did behind the scenes work for the Mayor’s administration.

The following year, Black Detroiters formed a number of Democratic clubs, which together changed Black Detroiters political path in lasting ways. Founded almost solely by Black women, Detroit’s Democratic Club built on the foundation of Murphy’s re-election campaign. Beulah Young, a Black woman journalist who also held a position in Murphy’s administration drew on the Murphy for Mayor Clubs to organize Black Detroiters into Democratic district-wide blocs. Additional Black women Democrats formed the Democratic Whip, a club exclusively for Black women. Mary Belle Rhodes headed up a woman’s auxiliary to the Democratic League, which was organized by Charles Diggs, Sr., Joseph A. Craigen, and Harold Bledsoe. These various Democratic organizations in Detroit resulted in an 88 percent increase in the amount of Black Detroiters aligning themselves with the Democratic Party from 1930-1932.

This new strength of Black Democrats in Detroit was responsible for the election of Michigan’s first Black state Senator; Charles Diggs, Sr. Diggs’ political trajectory was similar to the political development of Black Detroit as a whole. In the 1920s he was heavily involved with the Universal Negro Improvement Association and involved with the Republican Party. It was most likely in the UNIA where Diggs developed a commitment to Black self-reliance that played a role in his switching to the Democratic Party in 1932, and then played a role in his commitment to advocating for the rights of Black people once elected to the senate. He was responsible for “the Diggs Act,” legally known as the Equal Accommodations Act, passed in 1938, which made discrimination in public accommodations by race a misdemeanor. Elected to represent a district made up of Polish and Black Detroiters that was majority Polish, Diggs in many ways was the perfect embodiment of the civil rights-labor coalition. Diggs held his seat until 1944 when he was defeated in the Democratic primary after being convicted for accepting bribes along with 18 other State Senators.

Following in the footsteps of his father, Charles Diggs, Jr. was elected to the Michigan State Senate as a Democrat in 1951. Diggs was educated at Fisk University in Nashville, TN, and was a student at the University of Michigan Law School when he took the state senate seat vacated by his father.

The following year Black Detroiters elected the first African American woman in the country to hold a state senate office when they elected Cora Mae Brown to the Michigan State Senate as a Democrat representing the 2nd District. Brown, who had studied with the famous Black sociologist E. Franklin Frazier at Fisk University, worked as social worker in the woman’s division of the Detroit Police Department. She ran for office in both 1950 and 1951, losing both times before being elected in 1952. She was elected to represent the 3rd district during her second term. Brown worked in the Senate to increase the fine to business that violated the Diggs Act from $25 to $100.

The elections of Brown and the elder and younger Diggs created the conditions for an expansion of Black electoral power in the later 50s and the 1960s.

References:

Beth Bates, The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2012

Herb Boyd, Black Detroit: A People’s History of Self-Determination, New York, Harper Collins, 2017

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2007

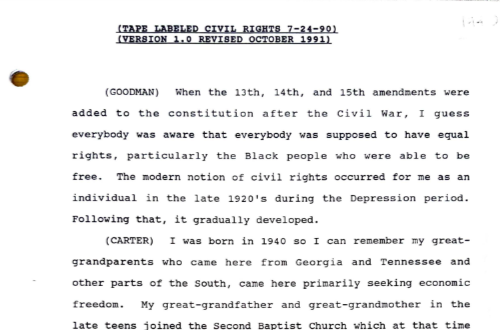

Oral history interview with Ernest Goodman, Richard Marks, and others, conducted by Elaine Latzman Moon in 1990. The group interview covers issues of civil rights and politics in Detroit in the early 20th Century. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

In this oral history interview from 1990, UAW Local 600 co-founder Dave Moore discusses Detroit Mayor Frank Murphy. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

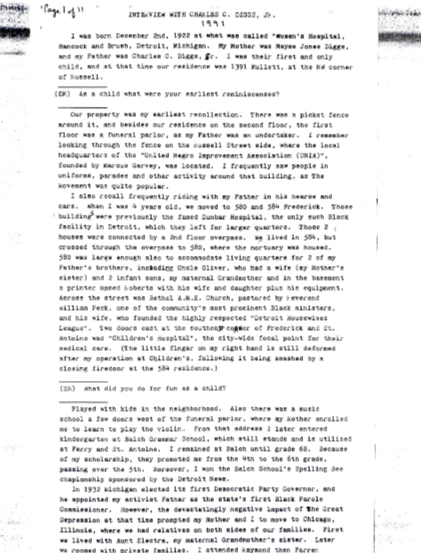

Oral history interview with Rep. Charles C. Diggs, Jr., conducted by Elaine Latzman Moon in 1991. Diggs discusses growing up in Detroit, his father’s political career, and his time in Congress. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

In August of 1954, twenty Black candidates won Democratic primary nominations in Detroit and around Michigan. This was the largest number of Black’s nominated in Michigan’s history and demonstrates the growth of Black political power in Detroit during the 1950s.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives

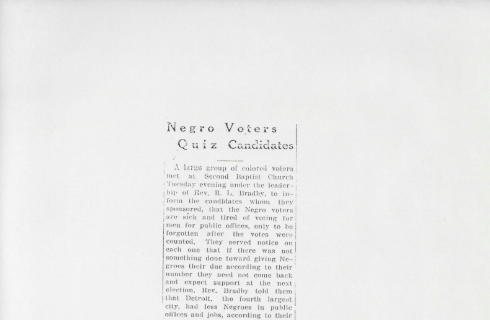

This article in the Detroit Tribune on November 4, 1933, reports that a “large group of colored voters” met at Second Baptist Church, where Reverend R. L. Bradby, informed them who the church is sponsoring for office that year. This article highlights the early political activism radiating from the church, as Bradby explains, because Black Detroiters were upset at politicans who paid lip service but provided no real solutions to their ills.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

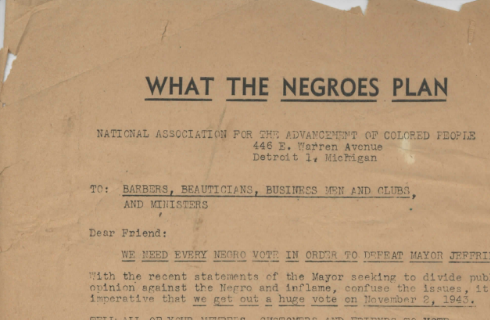

A letter from Detroit NAACP Executive Secretary Gloster Current urging “barbers, beauticians, business men and clubs, and ministers” to organize for the 1943 Common Council elections.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

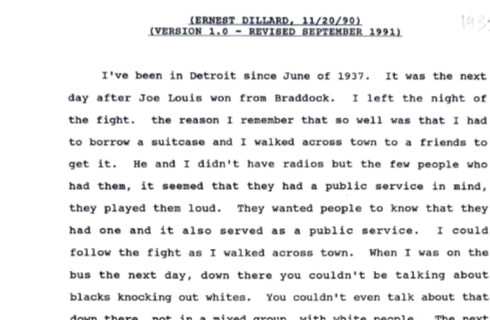

Oral history interview with labor and civil rights activist Ernest Dillard, conducted by Elaine Latzman Moon in 1991. Dillard discusses racism, segregation, and union organizing in Detroit in the 1940s-50s. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

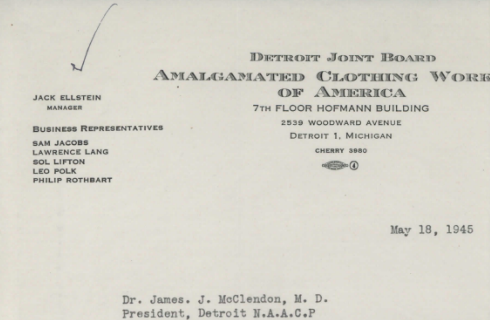

This May 18, 1945 letter from the Detroit Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America to then President of the Detroit NAACP, James J. McClendon, highlights the importance of McClendon’s fight against racism in Detroit in relation to the fight against facism during World War II.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

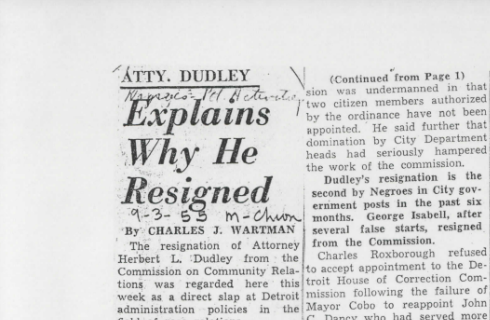

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations evolved from the City of Detroit Mayor’s Interracial Committee in response to the 1943 Detroit Race Riot. However, as this article from the Michigan Chronicle on November 3, 1955 explains, the commission never went far enough to address racial issues in the city, and many Black politicans, like Attorney Herbert L. Dudley, grew tired the empty promises.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Members of the NAACP pose for a group photograph in the offices of the Detroit Branch in 1955. Left to right: Arthur Johnson, Executive Secretary, Detroit Branch; Alex Fuller, Executive Vice-President, WCC; William H. Oliver, UAW-CIO Fair Practices Department; Dr. James McClendon, Detroit Branch; Edward M. Turner, Detroit Branch President; Hon. John A. Ricca, Judge, Recorders’ Court; Rev. Robert L. Bradby, Jr., Greater King Soloman Baptist Church; Joseph A. Craigen, Detroit Branch Vice-President.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

An article in the Michigan Chronicle from April 14, 1956, titled “Louis Martin Started Paper With Guts, $135: Consistent Interest in Betterment Of Negro Status Solidifed Paper.” The Michigan Chronicle, founded by Louis Martin in 1936, was one of Detroit’s premier African American newspapers. From 1936 to 1956, it was vital to keeping Black Detroiters informed of politics, economics, and racial issues in the city. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

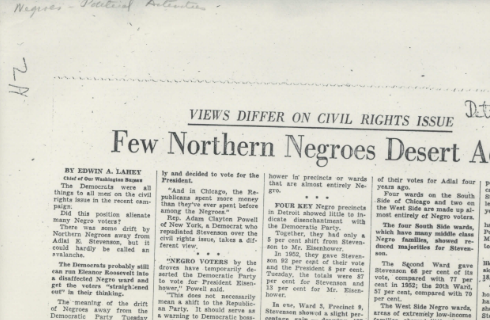

A November, 8, 1956 article from the Detroit Free Press, titled “Northern Negroes Desert Adlai” by Edwin A. Lahey. After World War II, Black voters aligned themselves with the Democratic Party and Detroit was a stronghold for Black political power and influence on the Democratic Party. Despite broad support for then President Dwight Eisenhower, this article from November 1956 in the Detroit Free Press explained that Black support for the Democratic Party still reigned supreme in the city.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A September 7, 1957 article from the Michigan Chronicle, titled “Largest Turnout: Negro Candidates in Tuesday’s Primary.” The late 1950s was a breakthrough for Black politics in Detroit. According to this article, the largest Black turnout ever shaped the 1957 election reflecting an energized political movement in the Black community.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

An undated photograph of Cora Mae Brown, the first African American woman to serve in the Michigan State Senate. –Credit: Black Past