Education

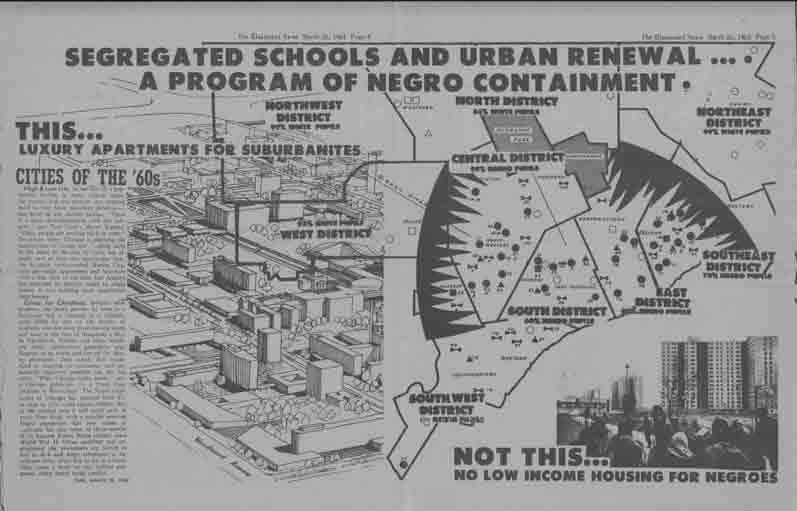

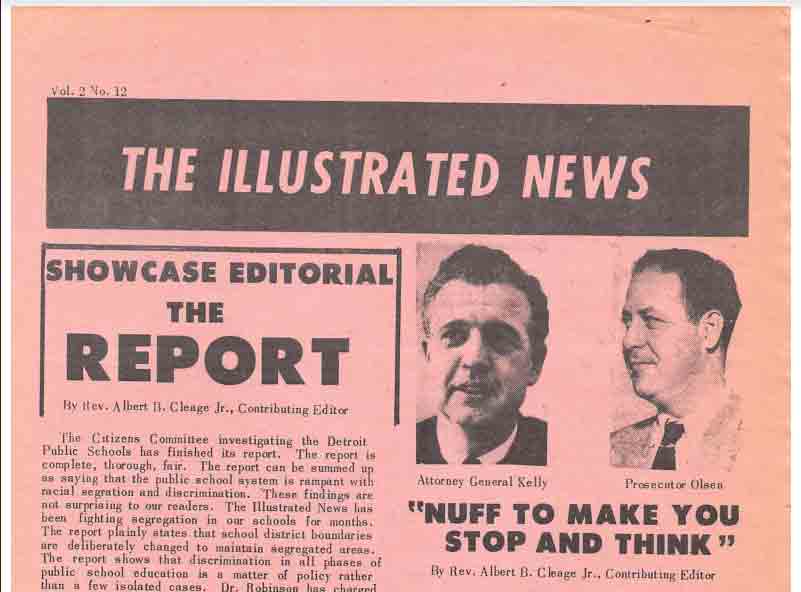

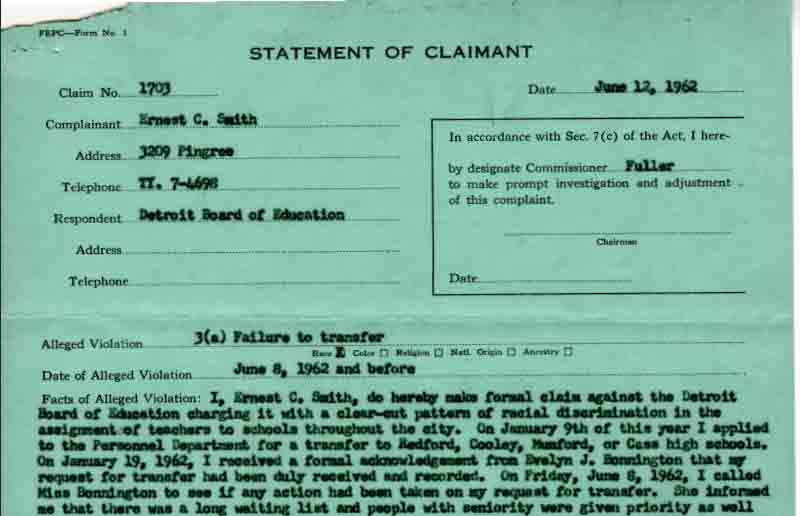

Detroit’s public schools were thoroughly segregated in the 1950s and 60s. In the early 1960s seventy-five of Detroit’s public schools were all white and eight were all black. 30 percent of schools were at least 90 percent white while the other 70 percent were at least 90 percent black. Only 89 schools in the entire system were made up of student bodies that had more than one racial group of students totaling higher than 10 percent. In schools with white students there were white teachers and no black teachers. All of the city’s black teachers taught in black schools as did some white teachers. Interpreting these numbers as evidence that Detroit ran a separate and unequal school district, black parents and students participated in several different mobilizations, tactics, and campaigns to improve the educational experiences of black children.

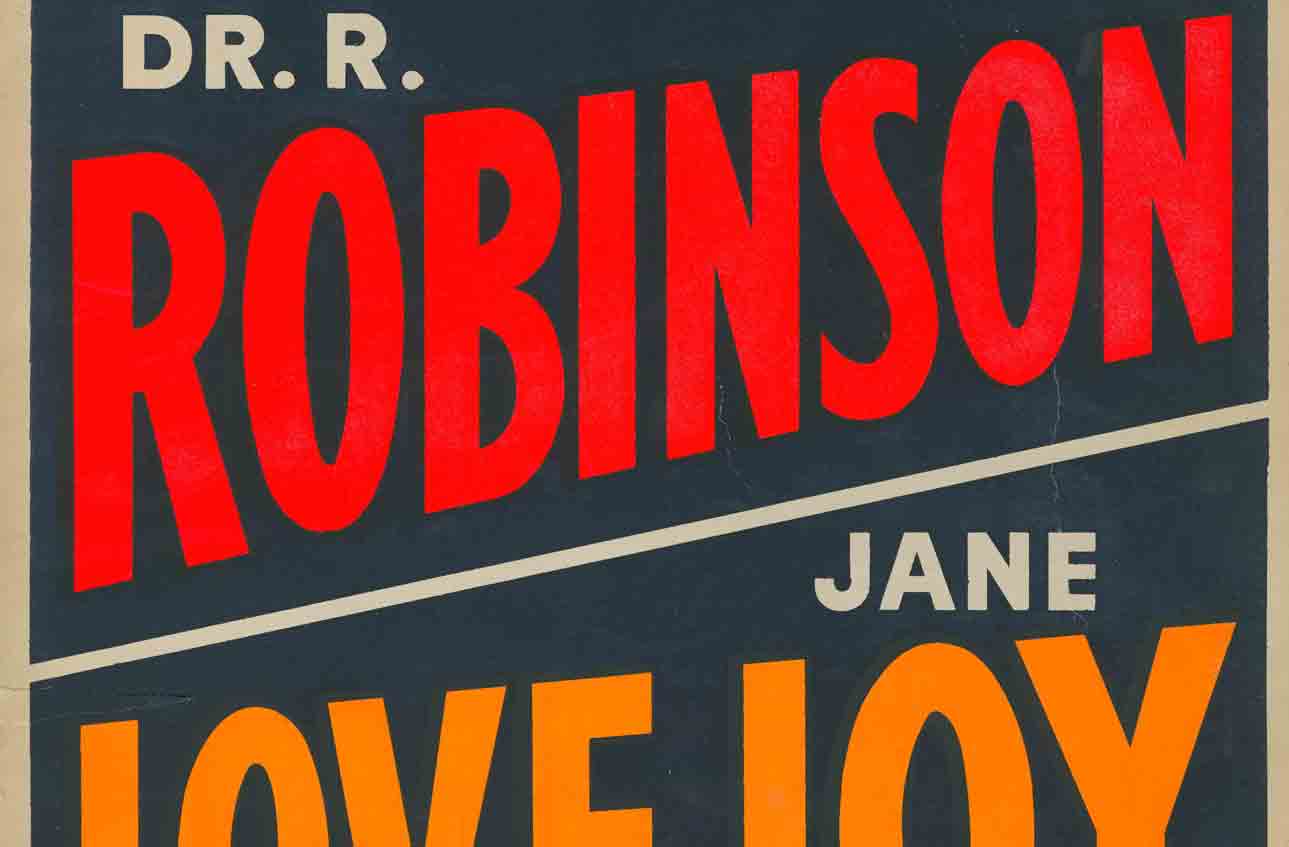

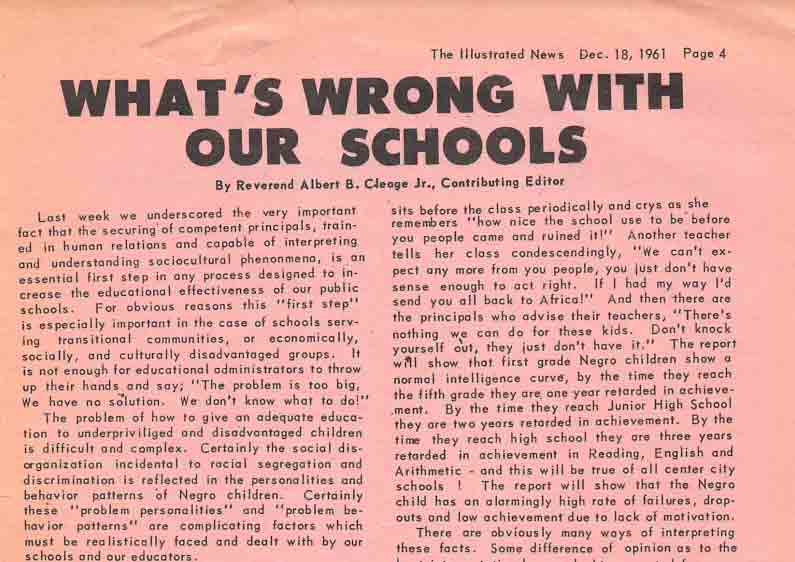

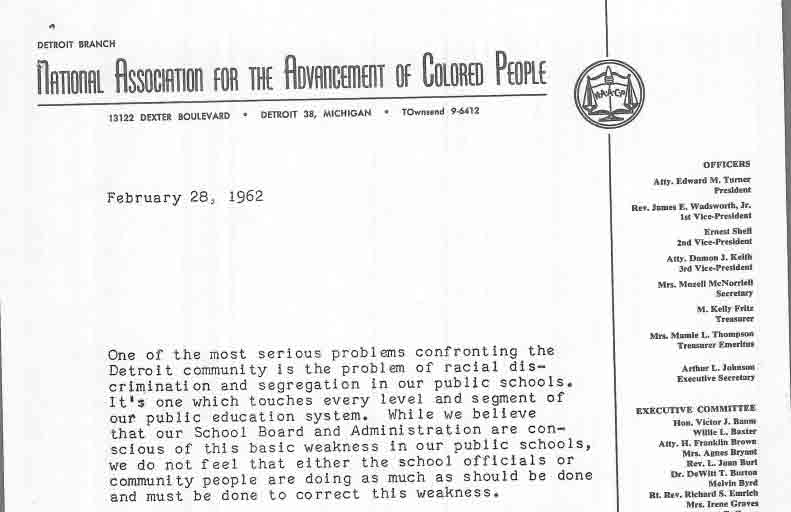

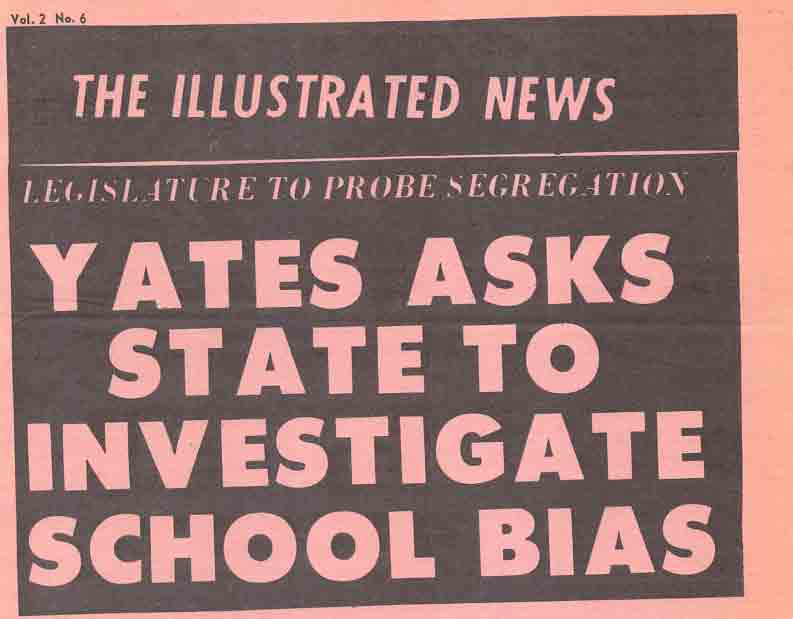

While black parents had long protested segregated schooling, mistreatment of their children by white teachers, deteriorating school buildings and materials, racist curriculum, and poor funding, in the early 1960s they began to experience some victories. Thanks to protest from a coalition of civil rights leaders, labor leaders, and the black press—as well as the election of the city’s first black school board member, Dr. Remus G. Robinson—in the early 1960s new schools were built in Detroit’s black neighborhoods and increased numbers of black teachers, administrators, and counselors were also hired. Despite these victories, problems remained and segregation persisted.

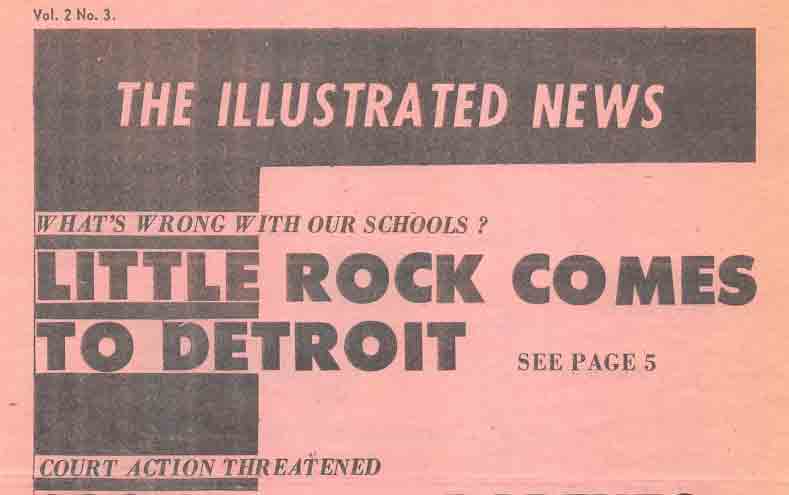

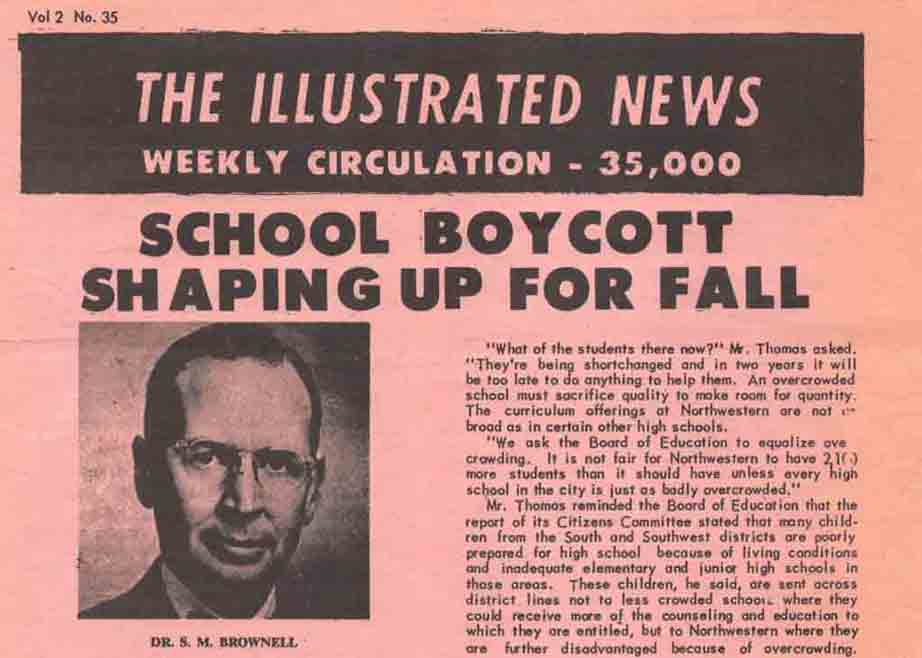

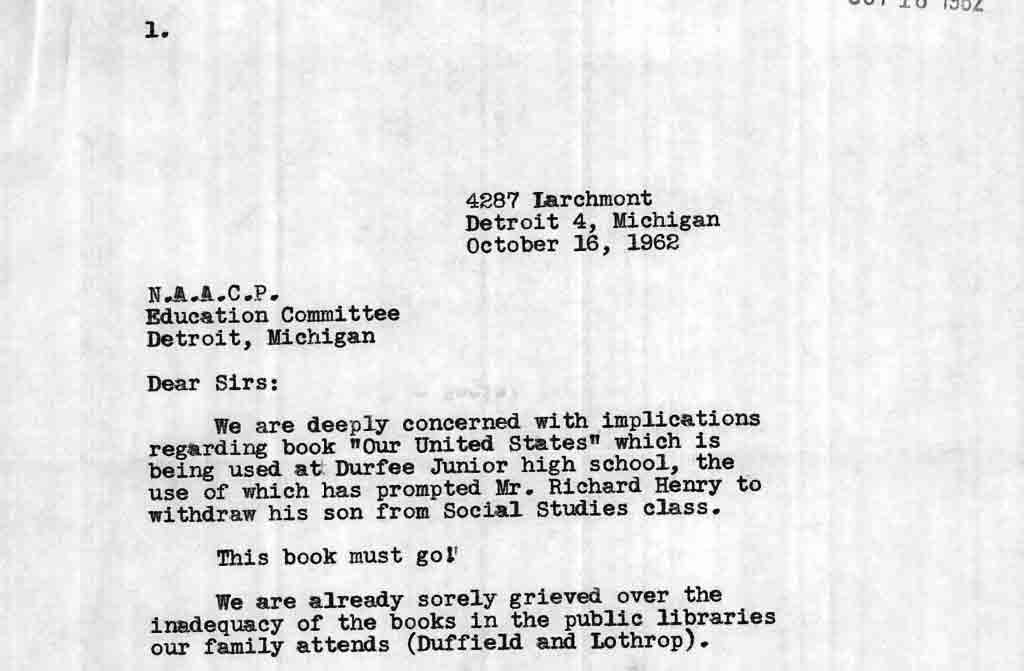

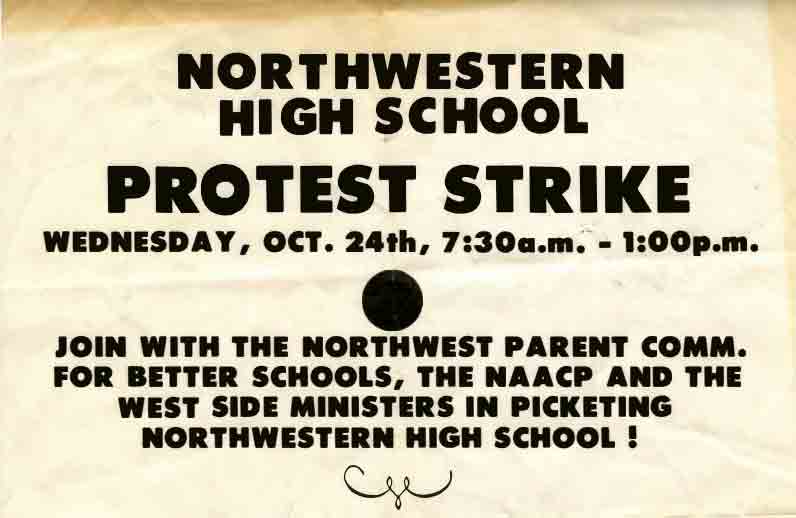

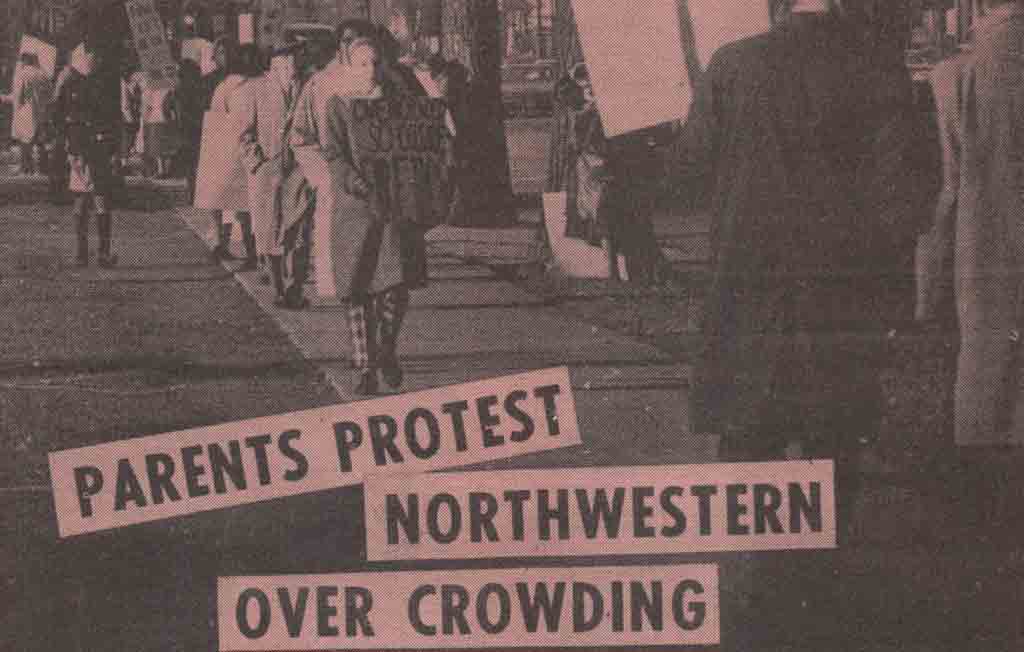

To address these continued problems, parents of students at Sherrill Jr. High formed the Sherrill Parents Committee. Especially upset at a redistricting plan that kept their children from attending a predominantly white high school, they approached GOAL (Group on Advanced Leadership) for help. While the NAACP offered to study the situation, GOAL organized a series of boycotts and pickets against the school. Although parents and students alike participated in the boycott, the school and Board of Education maintained their position. In response, GOAL attorney Milton Henry filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Parents Committee, charging the school with systematic mistreatment of black students, resulting from racist redistricting. Demanding a removal of racist textbooks and an increased number of black teachers and administrators, GOAL threatened a citywide boycott. Meanwhile, the NAACP defended the black president of the school board. In response to GOALs threat, the Board of Education added two supplementary chapters on black history to the curriculum while the suit was working its way through the legal system. A similar boycott occurred at Northwestern High School that same year.

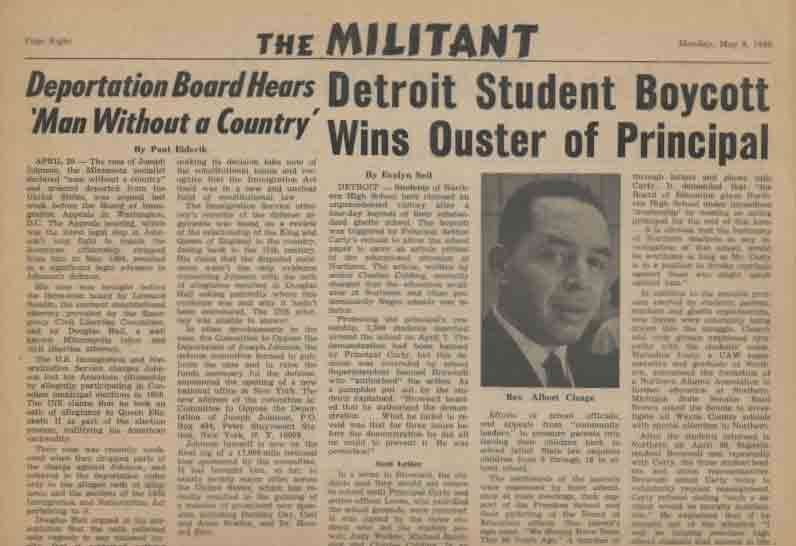

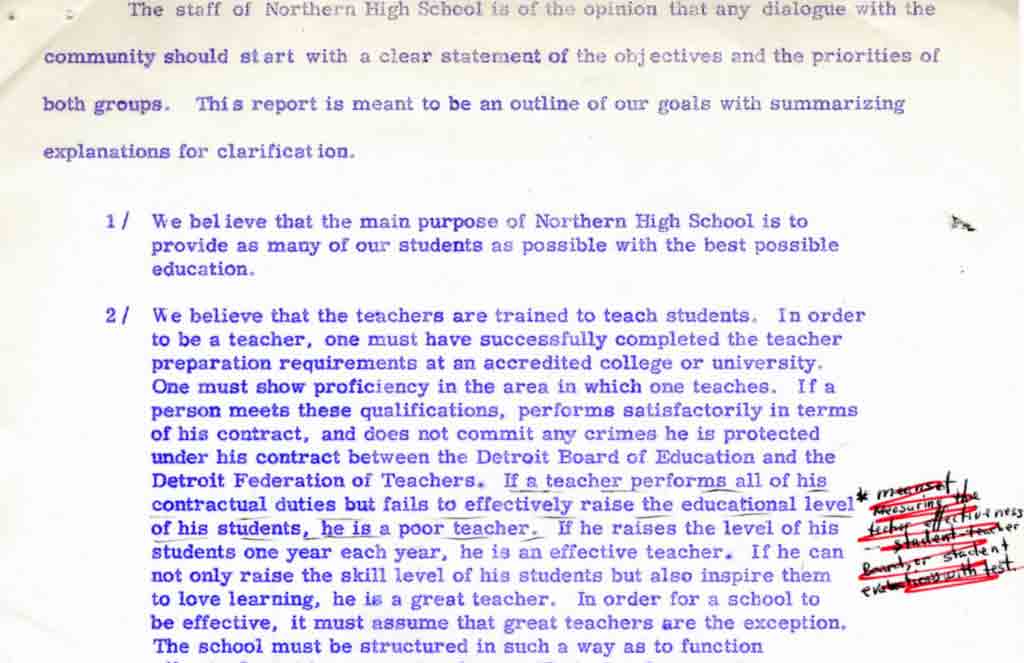

Most likely having developed an analysis of educational disparities at GOALs summer Freedom School, by 1966 black students themselves were leading the movement to improve schools in Detroit. When a student journalist at Northern High School wrote an article on the disparities between white and black schools that the paper refused to publish, students organized a walkout. Days later, 2,300 students walked out of school and joined parents in a protest demanding that the principal resign.

When the principal refused to resign, students transformed the walkout into a boycott. Demanding that the principle resign and a college preparatory education, on April 20, a full three weeks after the boycott began, only 183 of the school’s 2,307 students showed up for class. Speaking for the students, GOAL member Rev. Albert A. Cleage warned the school board that if they did not meet the students’ demands, they could expect more boycotts. Two days later, students from both Eastern High School and Southeastern High School joined students at Northern. When the principal agreed to step down for the remainder of the year, the students returned.

During the course of the boycott, both to continue learning and to prove that they weren’t just avoiding school, Northern High School Students organized a freedom school. Holding school all day and learning a variety of things from a curriculum they shaped, throughout the course of the freedom school, students consistently raised two fundamental questions. First, “Whose world is it?” If we really have a place in the world, without regard to our race or our economic background, why aren’t we being prepared for it?” Second, “Whose community is it? If it is ours…then we must have some effective control over the policies and practices of our community institutions—schools, police precincts, churches, etc.”

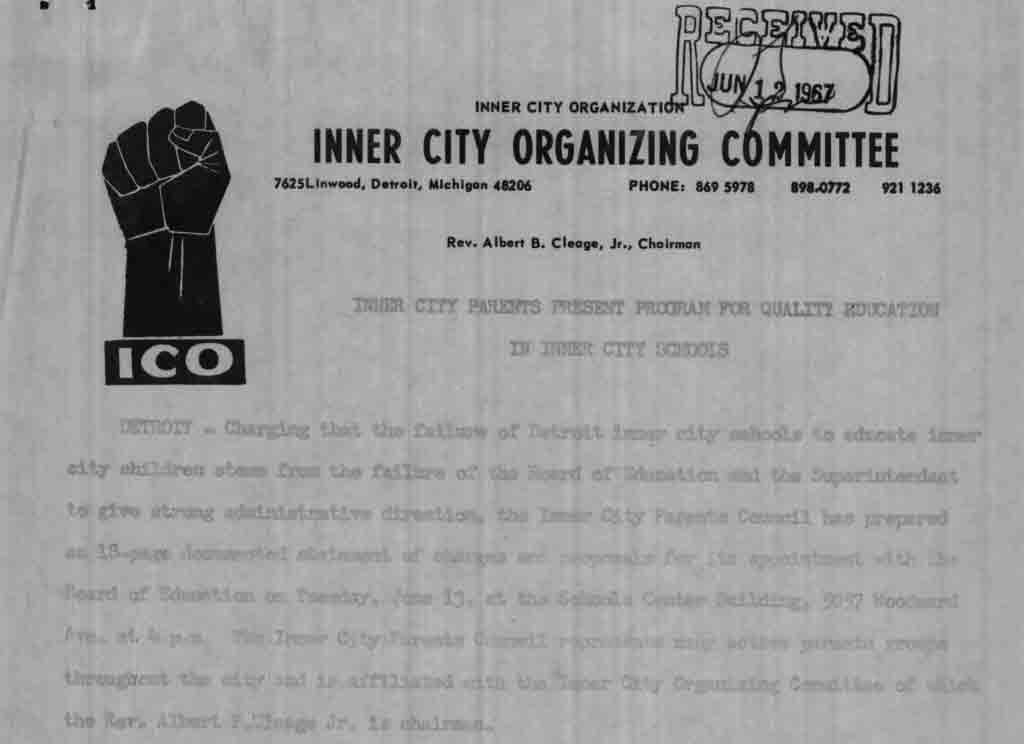

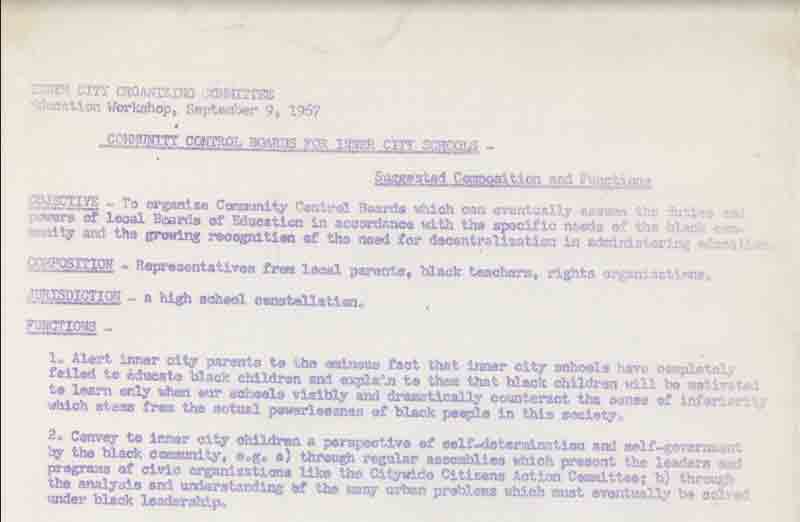

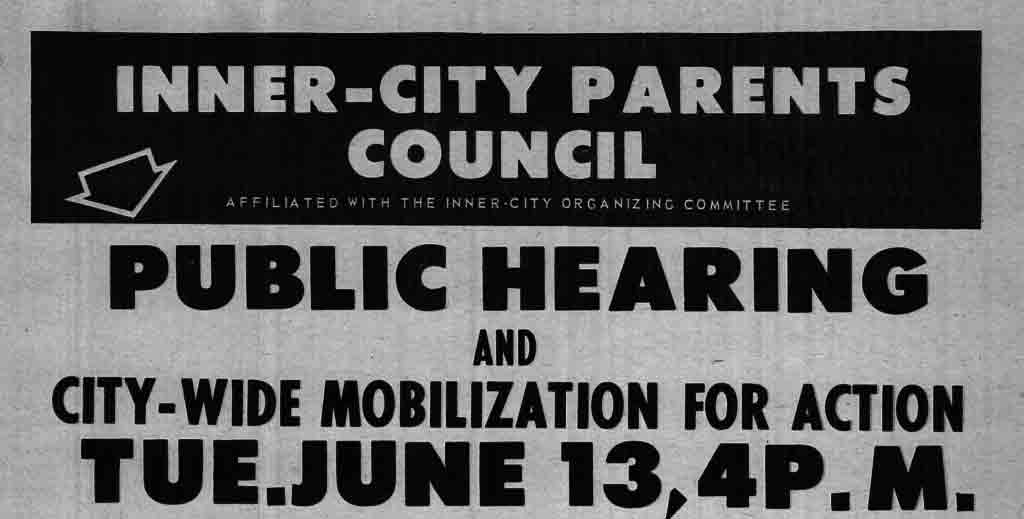

Building on the freedom schools organized by students at Northern, in 1966 black Detroiters also began to organize for community control of schools. The Inner City Parents Council, a program of the Inner City Organizing Committee (ICOC), developed its program for community control of schools in 1966. The ICOC demanded that staff vacancies in Detroit Schools be filled in direct proportion to the percentage of black students in a school and demanded the removal of all teachers whose students did not meet state defined minimum basic skills. The ICOC also demanded that the black community develop the curriculum for Detroit Public Schools and demanded that community arts groups be hired by the Board of Education to teach in Detroit Schools. This movement for community control would pick up after the 1967 Detroit Rebellion.

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2009

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967, East Lansing, MI, Michigan State University Press, 1989

Karl Gregory, “The Issues are Basic in Facing the Problems of Inner-City Schools,” Michigan Chronicle, May 28, 1966: A-9

“Segregated Schools and Urban Renewal … A Program of Negro Containment,” Illustrated News, Vol. 2, No. 13, March 26, 1962. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

A poster from Dr. Remus Robinson’s campaign to become the city’s first African American school board member in 1955. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

The Illustrated News, Vol. 2, No. 3 (January 15, 1962), featuring coverage of the Sherrill Parents Committee. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Article in The Militant by Evelyn Sell, “Detroit Student Boycott Wins Ouster of Principal,” (May 9, 1966). After students’ demonstration against censorship and inferior education at Northern High School, Principal Arthur Carty was removed by the Superintendent. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The Inner-City Parents Council of the Inner-City Organizing Committee advocated for teaching Black history and including Black principals and administrators in inner-city schools. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives

Flyer for a Northwestern High School protest strike, October 24, 1962. An invitation for Northwestern parents and children to picket the overcrowding and inadequate educational opportunities at the school. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

After the students of Northern High School protested their inferior educational opportunities during April of 1966, the Board of Education created an investigative committee to examine conditions at the school and make recommendations for change. Interim Report of Northern High School Study Committee, Detroit Public Schools, June 1966. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.