Resurgence of Black Nationalism

Believing that he could not be effective as the only black city council person in Pontiac, a Detroit suburb, in 1960, Milton Henry walked off the council and went to Ghana, West Africa. In Ghana he saw the Convention People’s Party, and saw “that people were organized around trying to get control of their lives.” According to him, “Now they were in a bag as far as these white corporations were concerned and they were in a bag as far as not really being able to get their lives organized, but at least they were trying to build ports and they were trying to build roads and I realized, as against what I had been doing, I was trying to get pavements and garbage and all that kinds of nonsense and that was the most routine aspects of life. It had nothing to do with trying to make life whole for our generation of people…. And that’s the thing I got in Africa. That people, even though they were poor and their standard of living was different they were working for a future that gave some promise to their people. Real hope for a decent life and for freedom and liberation.”

Having already grown to question how effective he—or any one black person—could be in electoral politics without a supportive cohort, Milton Henry found a new model for politics for Detroit in Ghana. In contrast to reforms, Henry saw Ghanaians struggling for control over a country and building a system, “to make life whole,” rather than improve aspects of the current system. With this seed of revolutionary politics planted, Henry returned to Detroit and began experimenting with ways to put what he saw in Ghana into practice in Detroit to make the lives of black Detroiters more whole.

Milton Henry’s observation paralleled with those of James and Grace Lee Boggs, two socialists in Detroit who were increasingly becoming critical of the labor movement and more receptive of Black Nationalism. In the late 1950s, they began to organize a program called Kenya Sundays in Detroit churches so that black Detroiters could hear “testimony of the tremendous creative powers that rests within people who are trying to develop themselves and once released, would be of such great value to people everywhere.” The Boggs’ local engagement with black church folk created space in which African revolutionary activity was put on the radar of everyday black Detroit activists who, in relationship to their own local activity, began to see that revolutionary African movements had a great deal to teach them about local struggle.

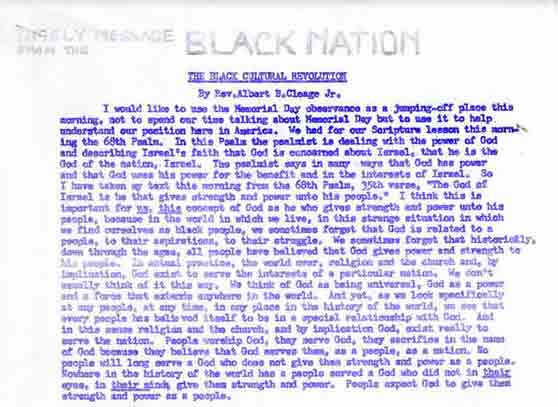

The Boggs’, Milton Henry, and those black Detroiters at Kenya Sundays all found an ally in Rev. Albert Cleage, the pastor at Central Congregational Church on Detroit’s West Side. Cleage, a black preacher who grew up in Detroit and resettled there in 1950 by starting his own church after he had been run out of St. Mark’s United Presbyterian Church by the church’s hierarchy for being too radical. Cleage’s church attracted large numbers of young people and professionals because of the way he combined theology, community organizing, and social criticism. Cleage was staunchly nationalist and was the kind of pastor who could equally relate to young gang members as he could to young professionals and elder blacks. Believing that half a million black people in the five mile radius of the church were all part of his parish, Cleage sent teams into neighborhoods to better know his base and invite them to church. He also attracted Milton Henry, his brother Richard, Ed Vaughn, and Grace Lee Boggs.

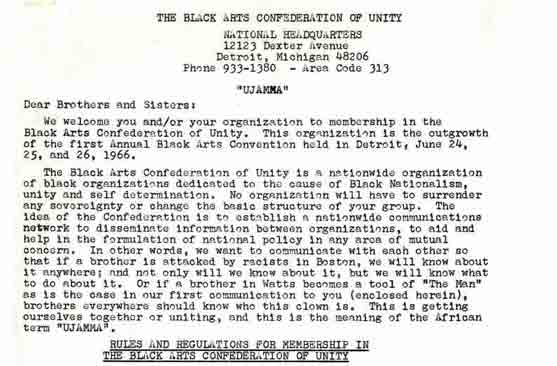

Ed Vaughn owned Vaughn’s Book’s on the West Side, Detroit’s first black bookstore specializing in titles related to black people. Vaughn organized weekly study groups at the store that attracted people from all over the city and facilitated the spread of nationalist ideas in Detroit and knowledge of African cultures. By 1964, the weekly gatherings had evolved into what people called “Forums” and culminated in Forum 66 and 67, which brought nationalist activists and artists in Detroit together with national figures from the Black Arts Movement.

Also active in this network of nationalists was a group of college aged revolutionary nationalists who formed an organization called Uhuru. Swahili for “freedom now,” Uhuru was devoted to building a nationalist united front and advocated armed self-defense. In 1964 several of their members went on a trip to Cuba, met members of the Revolutionary Action Movement, and became affiliated with RAM.

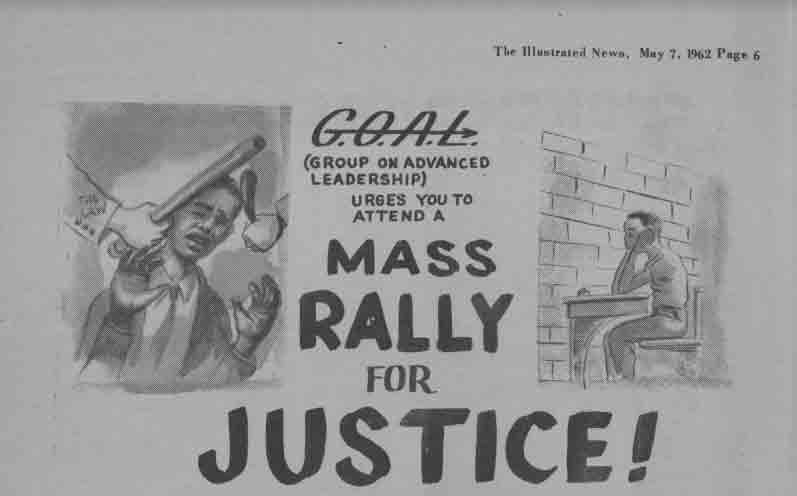

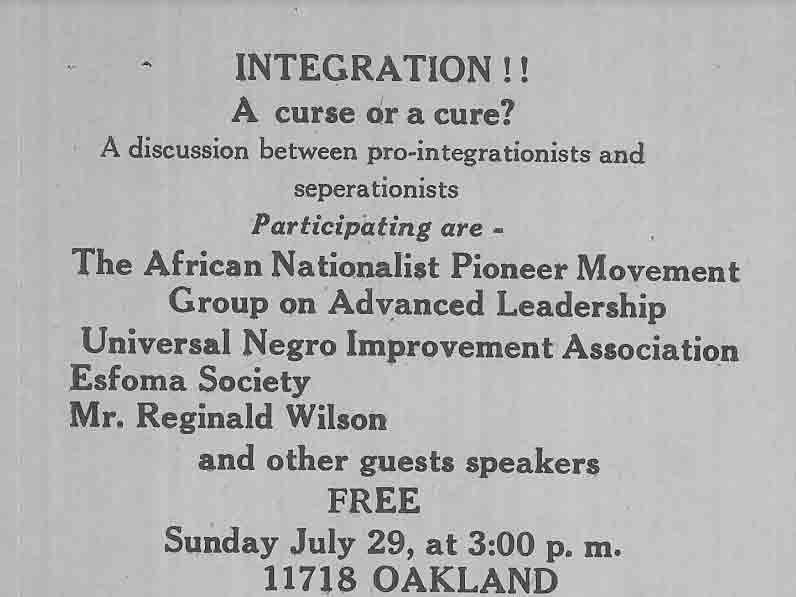

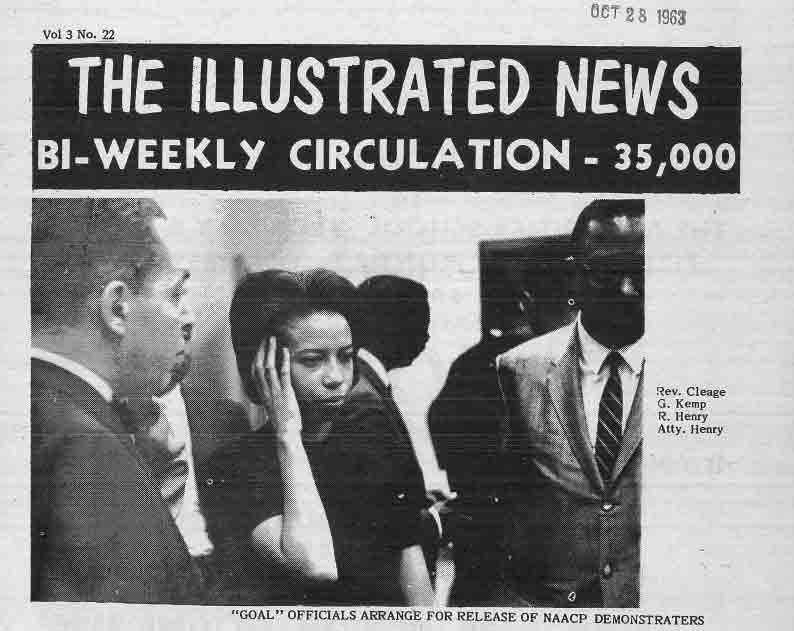

This network of nationalists self-consciously saw themselves as a radical alternative to the NAACP, CORE, and other civil rights groups both nationally and locally. Together, they were all active in GOAL (Group on Advanced Leadership). They collectively organized demonstrations against police brutality, and they all developed their own unique philosophies and strategies. Despite these differences, they came together to build the Freedom Now Party, and most significantly planned the Grassroots Leadership Conference in 1963, where Malcolm X gave his famous address “Message to the Grassroots.”

From 1964 through the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, this network of activists and activist-intellectuals were responsible for the spread of Black Nationalism and black power ideals throughout Detroit. Beyond these initial organizations, they came together during these years in organizations like the Inner City Organizing Committee, the Malcolm X Society, the AfroAmerican Student Movement, and in 1965, the Organization for Black Power. While they were not responsible for the Rebellion itself, the organizing, speaking, and agitating they did were a key part of creating the conditions that the Rebellion emerged from. They worked together after the Rebellion for a brief period before increasingly going their separate ways.

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Grace Lee Boggs, Living for Change: An Autobiography, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1998

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2009

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he describes Detroit’s involvement in the national Civil Rights Movement. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clips from 2018 interviews with JoAnn Watson, Frank Joyce, and Charles Ezra Ferrell, in which they discuss Black radicalism in Detroit in the 1960s and some of the most influential activists, organizers, and thinkers during that era. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Clips from 2018 interviews with Frank Joyce, Charles Ezra Ferrell, and Dan Aldridge, in which they discuss the lives and legacies of James and Grace Lee Boggs. –Videography: 248 Pencils

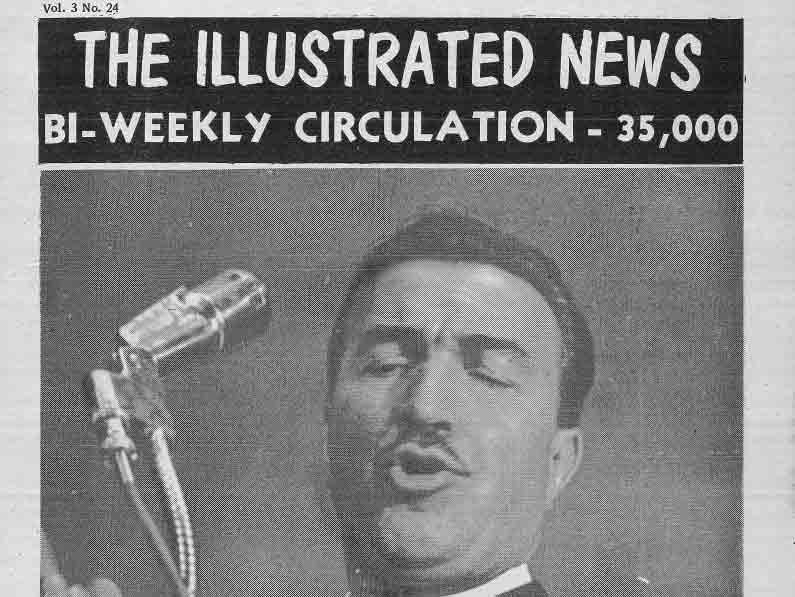

“The Next Step: A Three Part Analysis of the Black Revolution.” Illustrated News, Vol. 3, No. 24, November 25, 1963. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1989 interview with Ed Vaughn, in which he discusses Vaughn’s Bookstore and Black radical consciousness in Detroit in the 1960s. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from a 1988 interview with Detroit activist Ron Scott, in which he discusses Black radicalism in Detroit during the national Civil Rights Movement. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

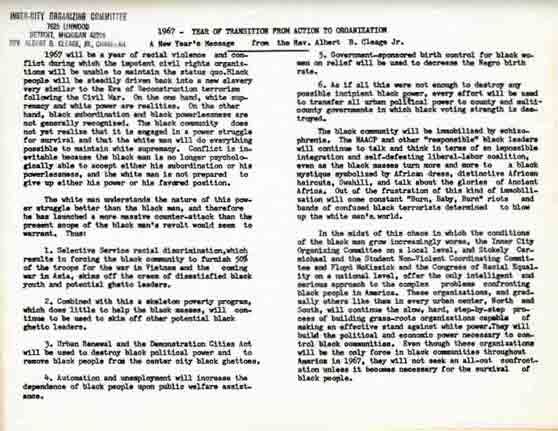

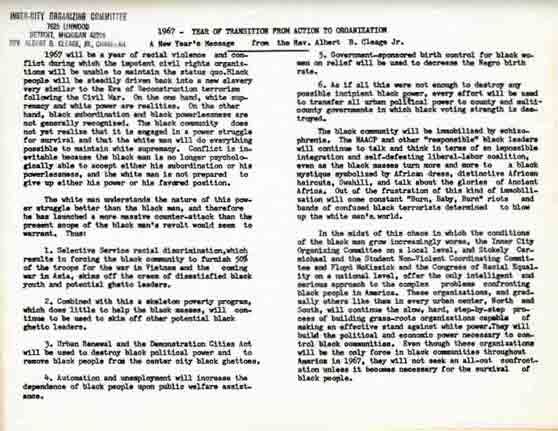

1967: Year of Transition from Action to Organization: A New Year’s Message from the Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr., chairman of the Inner City Organizing Committee. Cleage predicts, “1967 will be a year of racial violence and conflict…” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Explore The Archives

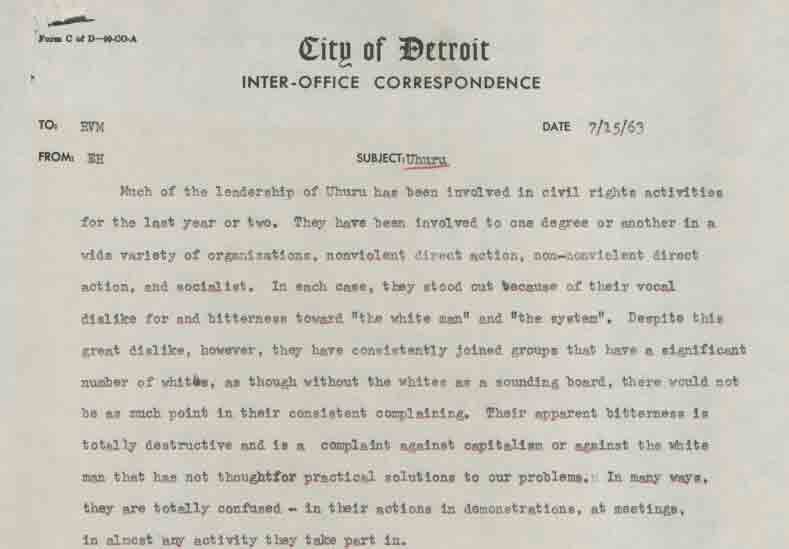

Memo from Richard V. Marks to EH at the City of Detroit regarding the student organization UHURU (July 15, 1963). –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

1967: Year of Transition from Action to Organization: A New Year’s Message from the Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr., chairman of the Inner City Organizing Committee. Cleage predicts, “1967 will be a year of racial violence and conflict…” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University