The National Civil Rights Movement in Detroit

Detroit was a city where black people embraced black power activism much earlier than in most other cities. Despite this embrace of black militancy, the national movement for civil rights also figured prominently in Detroit. When Mamie Till, the mother of Emmett Till, came to town after her son’s murder, she raised between $15,000-20,000 from the city’s residents and over 2,000 of them attended a rally at an AME church where she spoke to publicize the case of her son’s murder. The next year, Detroiters donated more than $35,000 to support the Montgomery Bus Boycott and individual black Detroiters donated cars to be used in it. In addition to the support Detroiters offered for movement developments in the South, national integrated organizations like the NAACP, CORE, and the Northern Student Movement (NSM) were active in Detroit. While the 1960s marked a serious decline for these organizations as black power’s prominence rose, in the 1960s they were all active in various struggles as well as in the 1963 March to Freedom featuring Martin Luther King.

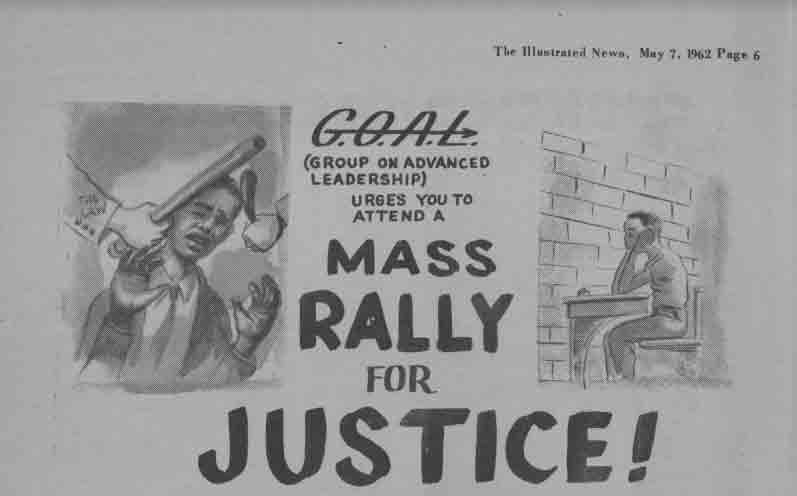

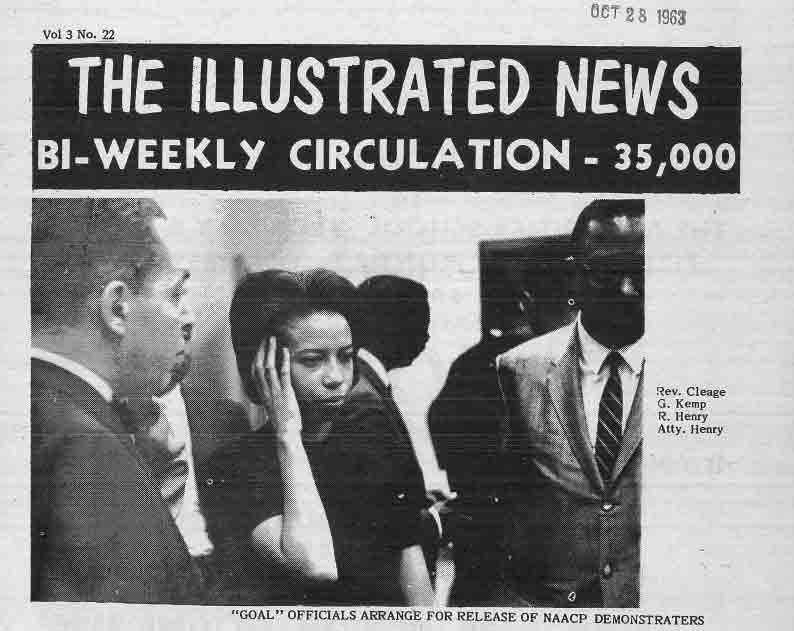

The Detroit chapter of the NAACP’s direct action rose to prominence in the 1940s and 50s when black autoworkers used it as a means to test the city’s anti-discrimination laws. Forming the Discrimination Action Committee in 1949, NAACP members organized sit-ins at restaurants along Woodward Avenue to protest illegal discrimination against black people. However, during the 1950s and 1960s, following the lead of the national office, its approach to activism in Detroit largely became less confrontational. Consequently, its local membership declined from 25,000 during World War II to just 5,162 in 1952.

Despite this drop in membership, Detroit’s NAACP played a major role in open housing activism in the city, it’s suburbs, and in mobilizing progressive white Detroiters for open housing drives. Organizing rallies and protests to demand open housing in Detroit suburbs like Royal Oak, Oak Park, Livonia, Dearborn, and Grosse Pointe, the NAACP was able to mobilize white supporters of open housing quite successfully. In 1962, white ministers created the Open Occupancy Conference, which worked to support NAACP drives for open housing in the suburbs. They convened a two-day conference that year resulting in a six-month research study on racial segregation. They then used the study to organize meetings amongst church members, talk about race, racism, interracial marriage, and encourage their members to sign open occupancy pledge cards.

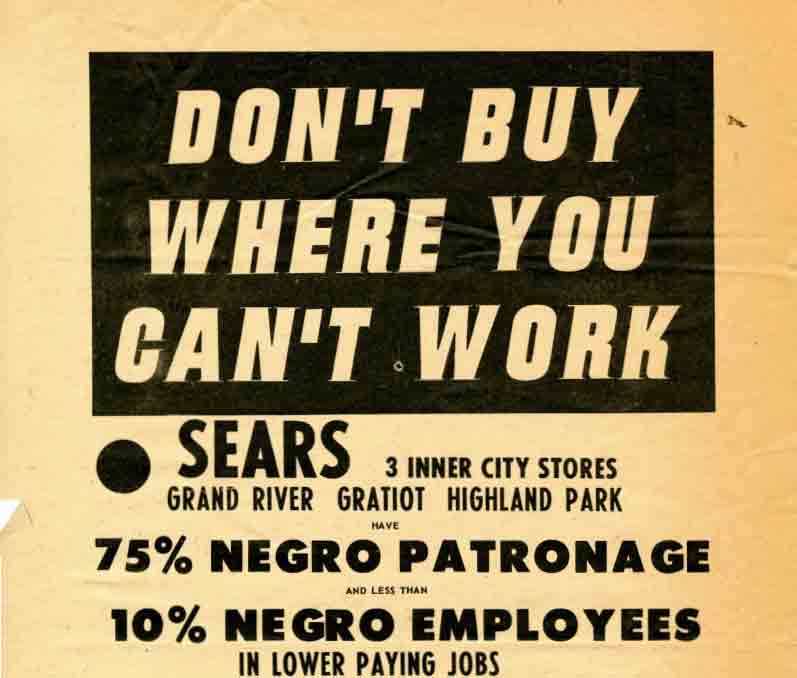

Detroit CORE (Congress on racial Equality) also played a major role in mobilizing white Detroiters to struggle for racial equality. In the early 1960s Detroit CORE supported the NAACP’s work in open housing, organized tenant rights groups in inner city Detroit, and struggled for jobs for black people. In 1964 Detroit CORE lead the national organization’s attempt to get the American Automobile Association to comply with fair employment practice laws, and in 1965 they successfully won back the jobs of several black workers in grocery stores who were fired for trying to organize a union.

CORE and the NAACP were also important partners in a larger collective effort to organize the 1963 Great Walk to Freedom in Detroit. Occurring June 23, 1967, the Great Walk to Freedom attracted over 125,000 participants and featured Martin Luther King Jr. as the keynote. Organized largely by Rev. C.L. Franklin and Rev. Albert Cleage, the march was officially organized by the Detroit Council on Human Rights (DCHR).

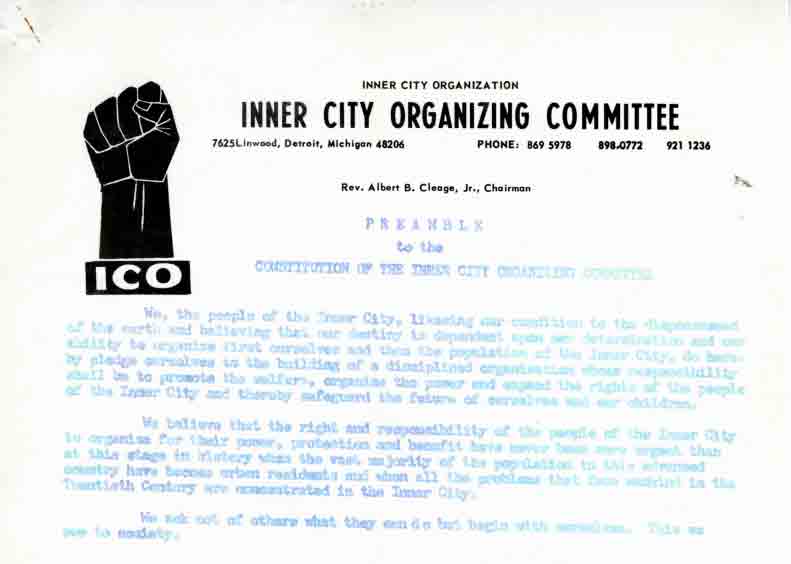

The march was a significant turning point in Detroit’s movement history because it marked the last time the NAACP played a major role in decision-making for a major movement event. While Cleage and Franklin insisted that the march be exclusively black-led, the NAACP refused to participate unless the DCHR opened the march to white leadership as well. Believing that they could not pull the march off without the support of the NAACP, Cleage and Franklin conceded their point and Mayor Jerome Cavanagh and Walter Reuther of the UAW played a leadership role in the march’s procession. During the rally following the march, Cleage called for a boycott of several grocery stores in the area in demand that they hire black workers. Following Cleage’s speech, Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech in what he saw as a rehearsal for the March on Washington that occurred later that summer.

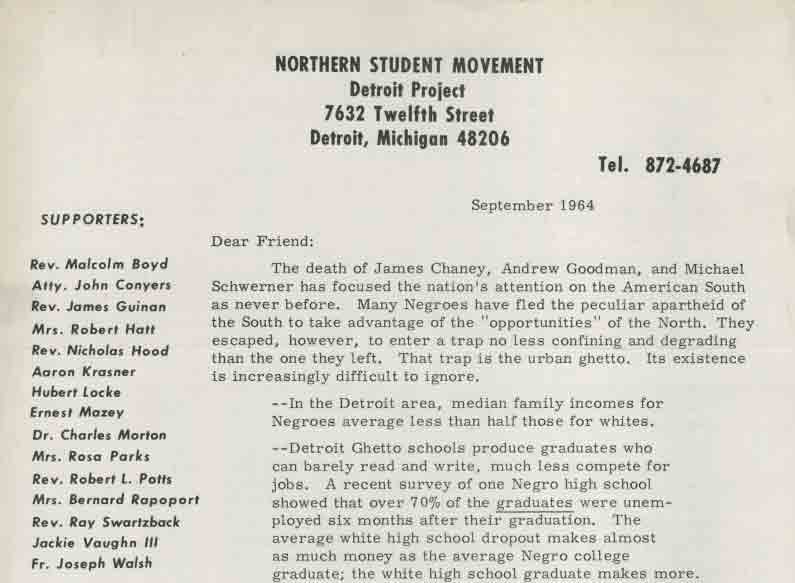

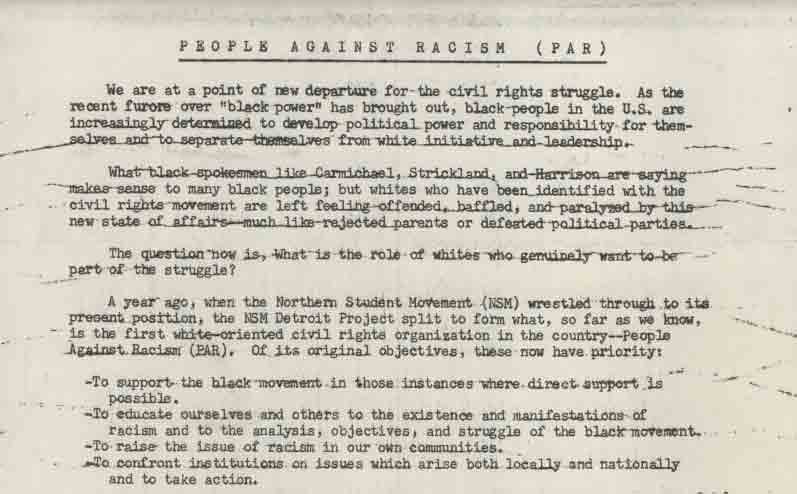

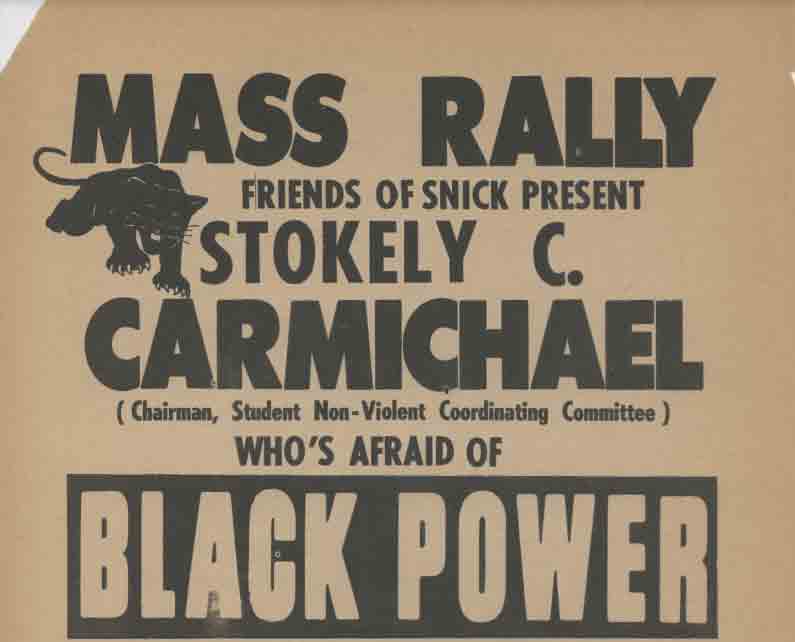

The tensions in the march planning between the NAACP’s position and that of Cleage and Franklin about white people’s role in the civil rights movement was a symptom of larger debates beginning to play out both nationally and locally. Detroit CORE began to fracture in 1961 around the role whites were to play in the movement and these fractures exacerbated in the period after the march. A year before the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) began the transition to an all-black organization, the Detroit chapter of the Northern Student Movement was taking up that question and organizing around it in innovative ways.

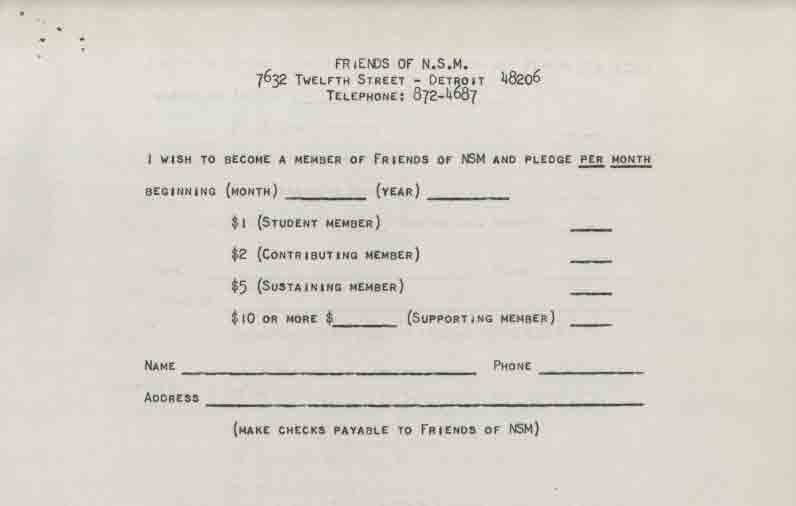

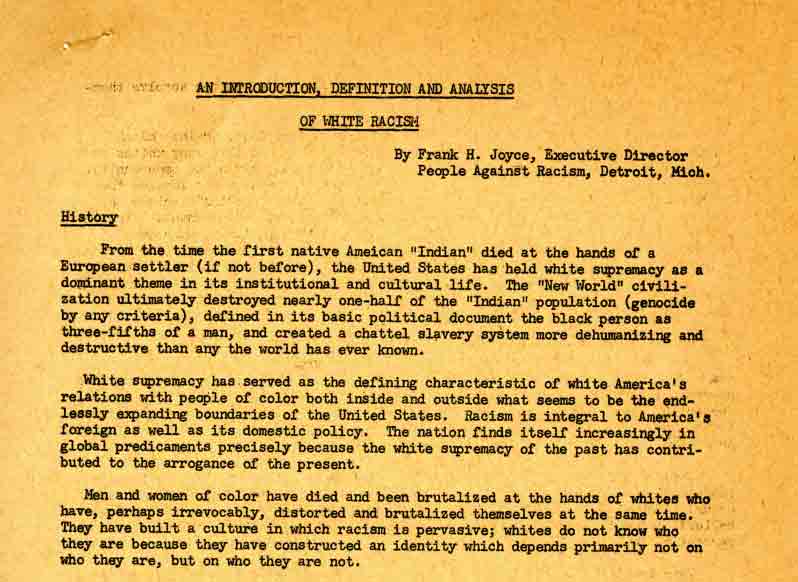

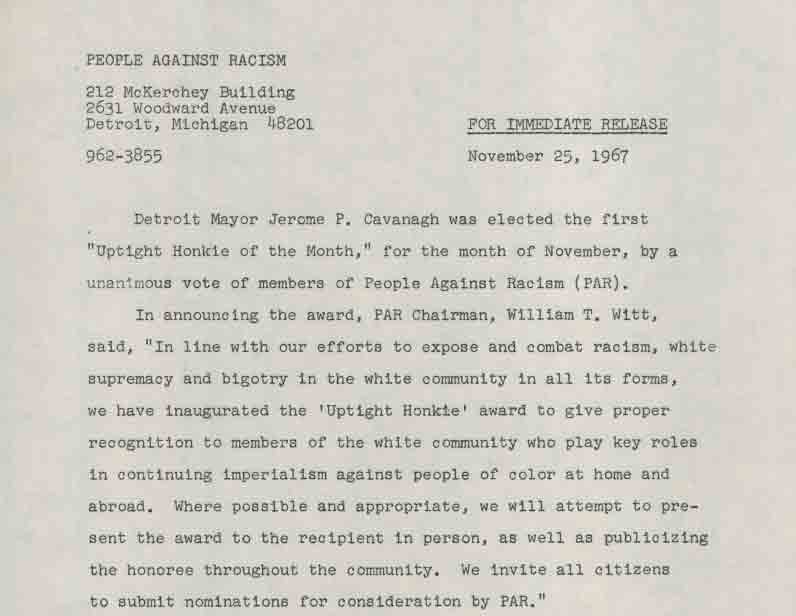

According to Frank Joyce, who founded the Detroit chapter of NSM, “Somewhere around 1965, a serious conversation began within NSM about the role of whites in what had always been a multiracial organization. The awareness grew that the more appropriate task of whites was not in helping blacks but rather in taking the antiracist struggle into the white community.” In response to this conclusion, NSM split into two organizations, NSM and Friends of NSM (FNSM). NSM became a black organization and FNSM became a white organization. Within about a year, FNSM expanded nationally and became People Against Racism (PAR). Often in conjunction with faith-based groups, PAR conducted workshops and race and racism, organized campus chapters, and participated in the broader New left movement more generally.

References

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2009

David M.P. Freund, Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2007

Crystal L. Johnson, The Core Way: The Congress of Racial Equality and the Civil Rights Movement, University of Kansas, Doctoral Dissertation, 2011

Frank Joyce, “It’s Time to Change the Water in the Fish Tank,” A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement and its Times, Ann Arbor, Michigan Publishing, 2015

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he describes Detroit’s involvement in the national Civil Rights Movement. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Members of the NAACP’s Housing Committee create signs in the offices of the Detroit Branch in 1962 for use in a future demonstration. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

“We Shall Overcome” by Reverend Albert B. Cleage. Cleage urges readers to participate in the upcoming Freedom March and to boycott A&P and Kroger stores over unfair hiring policies. Illustrated News, Vol. 3, No. 13, June 24, 1963. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 2018 interview with former City Councilwoman JoAnn Watson, in which she discusses Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1963 Walk to Freedom in Detroit. –Videographer: 248 Pencils

Clips from 2018 interviews with veteran Detroit activists JoAnn Watson, Frank Joyce, and Dan Aldridge, in which they discuss the various civil rights organizations that were active in the city and their relationships with the national Civil Rights Movement. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Clip from a 2018 interview with veteran Detroit activist Frank Joyce, in which he discusses the formation, evolution, and organizing actions of the Northern Student Movement in Detroit. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Explore The Archives

Members of the Detroit Branch of the NAACP pose for a photo during their membership campaign in 1959. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.