Urban Renewal

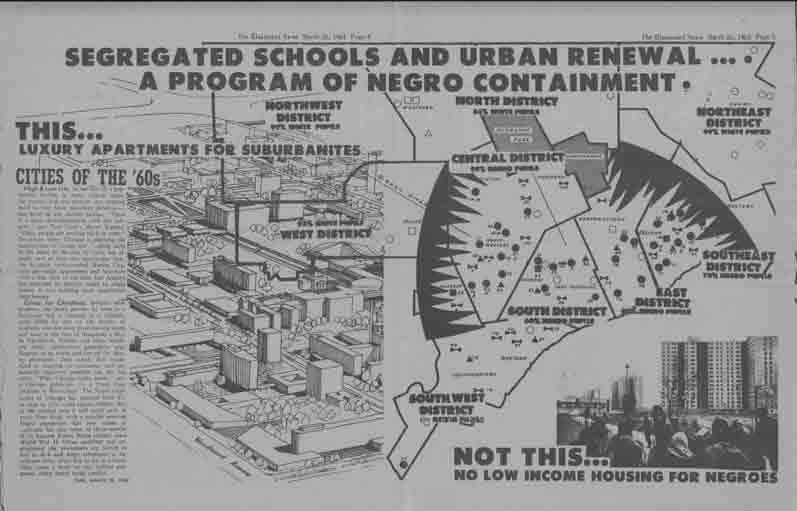

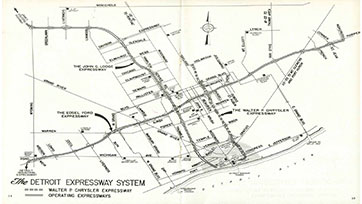

Between 1953 and 1967, urban renewal and highway projects worked to completely transform Detroit’s racial and geographic makeup. Before 1940, black Detroiters were concentrated on the East Side, primarily in Black Bottom and the neighborhood’s business district, Paradise Valley. By the 1960s, Black Bottom and Paradise Valley were gone, and the largest numbers of black Detroiters lived on the West Side, although significant numbers still lived on the East Side. These changes were driven by so called “slum clearance” of black neighborhoods and the construction of freeways right through black neighborhoods. The displacement of black Detroiters during this period was so grand, Detroit’s Urban League declared that, “No single governmental activity has done more to disperse, disorganize, and discourage neighborhood cohesion than has urban redevelopment.”

Because very little new housing was built in Detroit from the 1930s-1950s, by the 1950s much of Detroit’s inner city was old and decaying. As part of a plan to build new housing on Detroit’s near East Side and create economic development projects on the Near West Side, the city began to clear land in Black Bottom on the city’s lower East Side. Planners in Detroit were explicit about starting this process on the Lower East Side because they believed that in black communities, “There may be less likelihood of organized opposition,” and initially, planners’ assumptions proved to be correct.

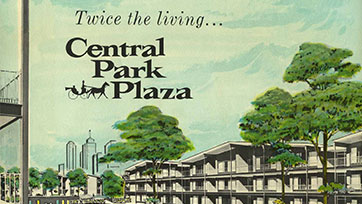

Black Detroiters did not initially resist these clearance projects because they assumed that dilapidated housing would be cleared for new public housing, as was the custom in Detroit. However, because land in Detroit’s inner city was priced higher than land in the suburbs and outer areas, realtors and Mayor Cobo agreed that urban renewal land should be replaced by housing for middle class and wealthy people. Out of the price range of most black Detroiters, this new housing resulted in the practical exclusion of black residents.

Fully aware that racial discrimination in housing meant that very few vacant apartments existed outside already black neighborhoods, the Detroit Housing Commission proceeded to clear out several hundred black Detroiters. Sending letters telling them to move without also informing that it was the city’s responsibility to help them find housing, most black families moved into older buildings on the West Side, doubling and tripling up with other families in already crowded houses. Some relocated with the assistance of the city to apartments and houses that, according to the city, had plumbing beyond repair.

After documenting the relocation process, the Detroit Urban League reported that many black Detroiters now lived in squalor as bad if not worse than the slums of Black Bottom, living in apartments with cracked walls, bad plumbing, and poor installation. The Urban League also warned that coming expressway construction would displace an additional 9,000 black families who would likely face similarly bad conditions after relocating.

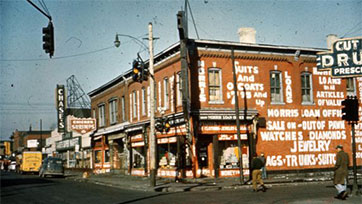

Expressway construction completely destroyed Hastings Street, the commercial center of Black Bottom, also known as Paradise Valley. Not only eliminating jazz clubs, churches, and other important cultural institutions, the destruction of Paradise Valley destroyed the sense of community that had existed amongst black Detroiters.

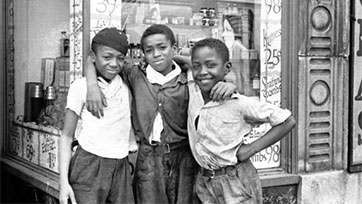

Small black owned businesses on and near Hastings Street were more than just a place to buy things. Owners often knew their customers very well, talking with them about their problems, sometimes supervising children, and even providing loans to some. Had these businesses been given relocation money that covered their costs, they may have been able to move with residents and maintain some sense of community. However, as one business owner told researchers, “I was not paid enough to start over into anything. If you wish to pass any information on you may say I feel very bitter over the way people in general were treated. It will not help to say anymore. I tried for many years and many meetings with people that lived in the area to get a better consideration. We did not get it.”

Instead of stores that built community, poor blacks new to west side neighborhoods consistently complained of being charged too much by white storeowners. Due to a contraction in the auto industry’s need for labor throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, unemployment was high in Detroit and black residents often relied on credit given to them by storeowners to get by. Many residents remember being ripped off by this credit system. For example, one resident remembered his mother receiving credit at a furniture store where the quality of merchandise was visibly poor. Because the store gave credit, his mother took what she could get and, as residents explained it, “the owners felt that the neighborhood was ripe for what they could afford so they priced accordingly.” Some storeowners went so far as to get customers drunk so that they would agree to high interest rates on big-ticket items. Other blacks found that white storeowners were willing to teach black residents what they knew about business, including how to cheat people with credit.

In this new environment, black Detroiters often lamented the loss of community that existed on Hastings Street and in Black Bottom. Although Marsha Mickens was too young to have experienced the cultural center, listening to her father who owned a record store on Hastings Street, she learned “that a way of life had been totally destroyed by the Chrysler Freeway.” Helen Kelly, who was forced to move from Hastings Street due to expressway construction said, “The expressway divided the community. When you could walk cross the street and talk to your neighbor, it’s no longer there. You got to go across the bridge, and after you go cross that bridge you ain’t going to find that same neighbor because that space, street, is gone—all those houses in that neighborhood is gone.”

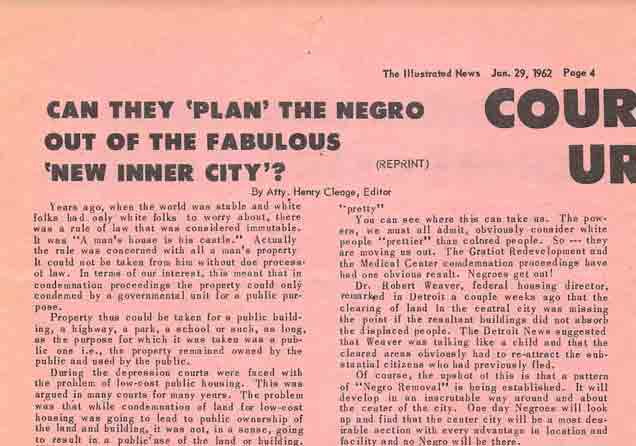

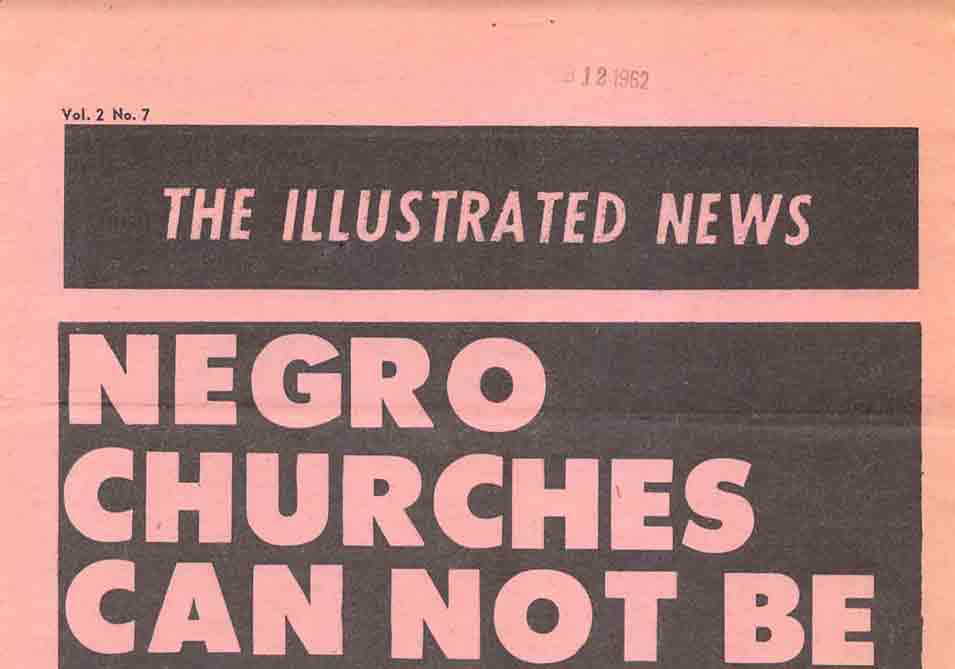

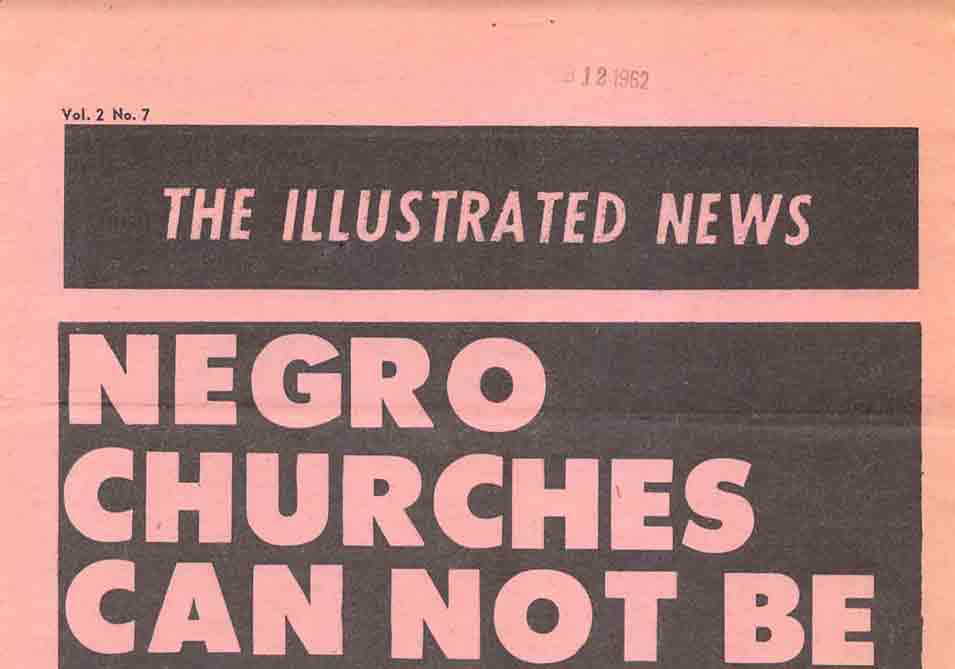

After experiencing this displacement from Black Bottom, black Detroiters started calling urban renewal “Negro removal,” and began to organize against it. GOAL (Group on Advanced Leadership) filed a lawsuit against the city to stop the construction of a medical center in what had been Black Bottom. In a coalition with the Urban League and black ministers, GOAL demanded that no black churches be torn down, that displaced residents and businesses be given financial assistance to return, and that the hospitals commit to ending racial discrimination in hiring.

Although the coalition was unable to get the city to agree to build low-income housing, the city did agree to protect black churches from demolition and some of these churches built their own low-income housing in the area. The coalition also succeeded in getting a pledge of non-discrimination from the hospitals, which resulted in better treatment for black patients and increased employment of black doctors, nurses, and orderlies.

References

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2009

Max Herman, Summer of Rage: An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots, New York Peter Lang, 2013

June Manning Thomas, Race and Redevelopment: Planning a Finer City in Postwar Detroit, Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 2013

Elaine Latzman Moon, Untold Tales, Unsung Heroes: An Oral History of Detroit’s African American Community, 1918-1967, Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1994

Interview with Helen Kelly, conducted by Blackside, Inc., June 9, 1989

Clips from 2018 interviews with Detroit attorney Elliott Hall and former City Councilwoman JoAnn Watson, in which they explain how freeway construction and urban renewal programs have impacted the city of Detroit. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Neighbors on Mullet St. in 1950 gather on their front porches in Black Bottom, a neighborhood that was demolished in the 1950s to make way for the Chrysler Freeway and the Detroit Medical Center. –Credit: Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

Clip from a 2018 interview with former City Councilwoman JoAnn Watson, in which she describes the Black communities that were destroyed when freeways were built through the heart of Detroit. –Videography: 248 Pencils

A view of the Chrysler Freeway construction project in Detroit, looking east from the roof of the City-County Building (undated). –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Helen Kelly, in which she describes the impacts that urban renewal and highway construction had on the city’s Black community.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

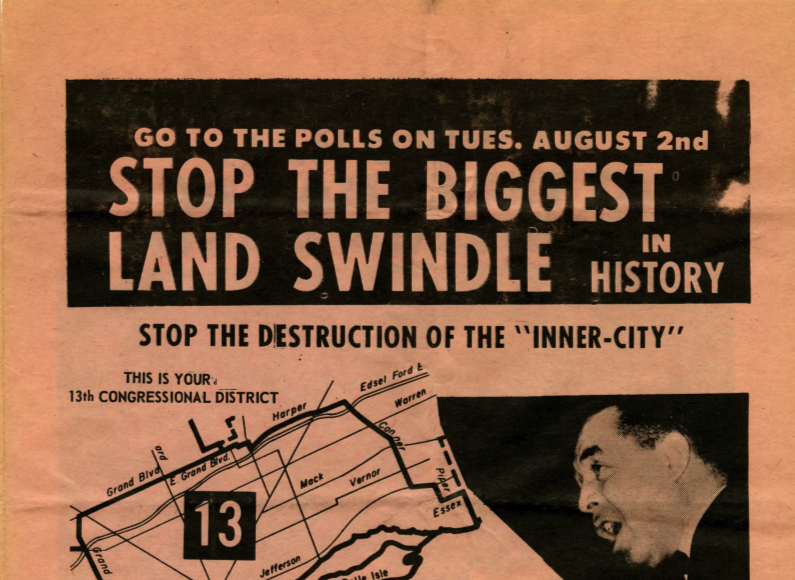

In 1965, the Reverend Albert B. Cleage, Jr. ran for Detroit’s Common Council. He campaigned on a promise to fight police brutality and stop the destruction of the inner-city through urban renewal. “Stop the Biggest Land Swindle in History. Stop the Destruction of the ‘Inner-City.'” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 1989 interview with Ed Vaughn, in which he discusses urban renewal and highway construction in Detroit, and community resistance in the 1960s.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

Detroit native Horace Sheffield describes growing up in the African American community on the West Side of Detroit in the 1920s-1930s.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Detroit resident Shelton Tappes describes the neighborhood he grew up in during the 1920s-1930s before it was destroyed by highway construction in the 1950s.–Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries