Police and National Guard

According to historian Sidney Fine, the behavior of police during the Detroit Rebellion became, “in some degree, a riot of police against blacks.” Many black Detroiters quickly began to perceive that the police were using the Rebellion as an excuse to act out their racism and take revenge on the city’s blacks. As the police began killing people—black children included—this perception spread widely.

One of the first people shot by state officials was thirteen-year-old Albert Wilson. On Sunday the 23rd, after he saw state troopers stab his neighbor with a bayonet, Wilson ventured to 12th street. Once there he saw people carrying safes and other looted goods, describing what he saw as “carnival like.” This atmosphere shifted when he and some neighbors entered an already broken into five and dime store and was shot. While in the store, Wilson heard, “All you motherfuckers, Black motherfuckers, come out from back there.”

“I was the only one who stood up. I was asked not to by the neighbors. I saw them, my neighbors very clearly, who told me not to go out and not to stand up. And I remember telling them, “I’m going out.” And at that point, I stood up to go towards the door. I did go to the door, to the archway of the door and I saw the gentleman standing there, with the gun, pointed towards me and, ah, I remember turning around to go back where my neighbors were because they told me to stay there. I knew that there was no other way out of there because they had looked and all of the back doors were barred and so I guess that were kind of penned in.”

The “gentlemen” Wilson referred to then shot him in the back, striking his spine. Wilson was left paralyzed by the officer’s bullet. True and untrue stories like Wilson’s spread quickly throughout the city.

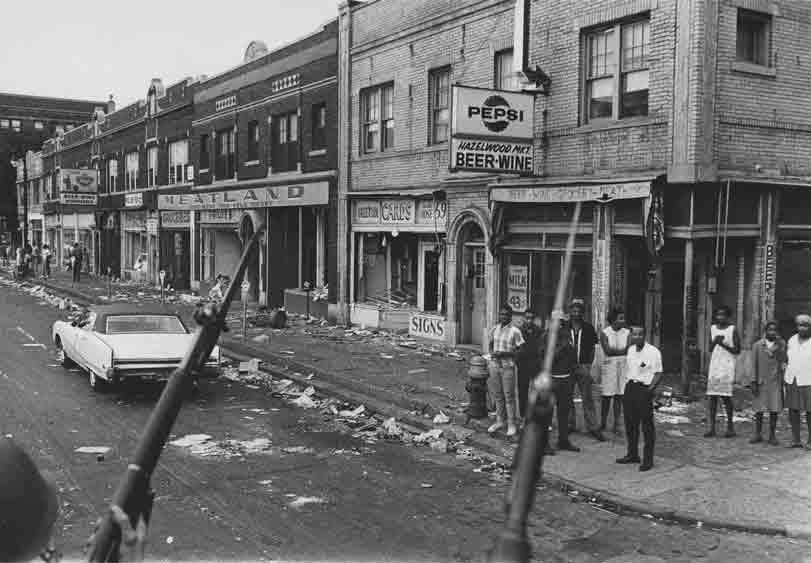

Under the conditions of military occupation, the spread of story’s like Wilson’s created vast fear amongst many black Detroiters. While police rode through the city four deep to a car with shotguns out the window, the National Guard patrolled the West Side in tanks and low flying helicopters looking for snipers. Upon seeing a tank in the alley behind her house, Daisy Nunley recalled, “I thought that the tank was going to come down and it was getting ready to level out our block, that’s what my thoughts were. And I knew my children were downstairs and I think I made a jump from the top step downstairs and I went and I started, I started gathering them up and I said we had to get to the basement, it was like, ‘Get to the basement!’ I was screaming and hollering and I was trying to get them down to the basement because I didn’t know what this, I just thought that this tank was coming to, to, to shoot down the block….”

Nunley was not overreacting. On July 24 alone, police officers killed seven black men and the National Guard killed another four.

On the third day of the rebellion, the National Guard used a tank mounted .50 caliber machine gun to fire into an apartment where they saw a spark. Firing several shots at what they assumed was a sniper, they pierced the lung of Tanya Blanding, a four-year black girl. Blanding died almost instantly of massive hemorrhaging. The Detroit News described what happened, “The assistant gunner pointed towards a flash in the window of an apartment house from which there had been reports of sniping. The machine gunner opened fire. As the slugs ripped through the window and the walls of the apartment, they nearly severed the arm of 21-year old Valarie Hood. Her four-year-old niece, Tanya Blanding, toppled dead…. A few seconds earlier, 19-year-old Bill Hood, standing in a window, had lighted a cigarette.”

Also, under the premise of sniper activity during the third night of the rebellion, Detroit Police and the National Guard forcibly entered a room at the Algiers Motel, near the geographic center of the city. In the hotel were two white women and seven black men who took up residence at the hotel popular for prostitution and drug use to stay out of harm’s way during the rebellion. As police kicked in the door, they shot one black male teenager on sight. After killing the teen, police tortured other residents to solicit information about where the sniper was. Over the course of interrogation, the police murdered two more black men and terrorized the two white women viciously. No weapon was ever found.

References

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967, East Lansing, MI, Michigan State University Press, 1989

BJ Widick, Detroit: City of Race and Class Violence, Detroit, Wayne State University Press

Interview with Albert Wilson, conducted by Blackside, Inc. on November 1, 1988, for Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads 1965 to 1985. Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection.

Interview with Daisy Nunley conducted by Blackside, Inc. on June 5, 1989 for Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads 1965 to 1985. Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he explains how police “rioted” during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Three National Guardsmen patrol the corner of Hazelwood and Linwood with weapons drawn as residents from the neighborhood look on. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Daisy Nunley, in which she describes the presence of the National Guard and federal troops in Detroit. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

In this clip from WWJ-TV’s “Six Days in July,” Detroit residents describe acts of violence inflicted upon the community by police and the National Guard during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, including the death of four-year-old Tanya Blanding. –Credit: Click On Detroit (clickondetroit.com/1967-detroit-riots)

Clips from 2018 interviews with Detroit activists Frank Joyce and Dan Aldridge, in which they discuss the People’s Tribunal of the police officers who killed three Black teenagers at the Algiers Motel during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Explore The Archives

Clip from a 1988 interview with Detroit activist Ron Scott, in which he describes an encounter with the National Guard during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A statment issued by People Against Racism, an outgrowth of the Northern Student Movement, in response to the brutality of city and state police, National Guard, and federal troops during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. In this statement, PAR explains the roles of law enforcement in maintaining “white power in the ghetto.” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Herb Boyd, in which he describes the actions of the National Guard during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. During many of the urban rebellions of the 1960s, including Detroit and Newark, the National Guard were seen by Black communities as a brutal, occupying force within Black communities. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Soldiers pose for a photo in a military vehicle with a high-caliber mounted gun. As in many cities that experienced urban rebellions in the 1960s, the majority of law enforcement that arrived in the city was white and unprepared for urban conflict.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident and National Guard member Howard Holland, in which he explains the roles played by the National Guard during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. Although many in the National Guard, like Holland, viewed their mission as protecting the community during the uprising, many African American residents of Detroit saw the influx of police, National Guard, and federal troops as an occupying force in the city. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Soldiers with bayonets affixed to their rifles watch over a small crowd on the street corner from atop a military vehicle. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1988 interview with former US Assistant Attorney General Roger Wilkins, in which he describes the actions of Michigan State Troopers during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A police offer stands guard for a crew of fire fighters battling one of the many fires caused be arson during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident and owner of Vaughn’s Bookstore, Ed Vaughn, in which he describes the destruction of his bookstore by members of the Detroit Police Department. During many of the urban rebellions of the 1960s, most Black-owned businesses and others that treated their Black customers fairly were generally left alone, while businesses that exploited or discriminated against Black customers became targets for looting, vandalism, or arson. In Detroit, Newark, and other cities, however, police officers and National Guardsmen were alleged to have targeted Black-owned businesses for retribution. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

On July 25, 1967, police raided the Algiers Motel on Woodward Avenue looking for rumored snipers. While questioning motel guests, police killed 3 Black men in the hotel, beat 9 others, and found no snipers. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Herb Boyd, in which he addresses rumors of “snipers” during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. During many of the urban rebellions of the 1960s, rumors circulated that armed “snipers” were perched in windows and targeting law enforcement and fire fighters. The majority of these rumors were unfounded, but resulted in National Guard and police firing indiscriminately at suspected snipers in buildings, sidewalks, and cars.