The Community

On the first morning of the Rebellion, NAACP president Arthur Johnson, Congressman John Conyers, and Damon Keith, a Detroit lawyer and chair of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, led a meeting at Grace Episcopal Church to develop a plan to de-escalate the situation in the streets. Understanding that police were heavily armed and ready for confrontation, they concluded that the more aggressive police were, the more aggressive people in the streets would probably become and that such a confrontation would be a bloodbath. To prevent such a bloodbath, they agreed to go into the heart of the disturbance and encourage people to stay off the streets to avoid being killed. When Conyers got to Twelfth Street in a car driven by Arthur Johnson, he was jeered and ignored. Standing on the hood of Johnson’s car telling people to go home, they told him, “We are home,” and “Tell the police to go home.” Deciding they were powerless over the people in the streets they went home.

In response to the anger and violence in the streets, black radio station WJLB cancelled its regularly scheduled programming in favor of trying and convince black Detroiters to restore peace. Martha Jean the Queen hosted programming for forty-eight hours straight in an attempt to get people to go home and stay off the streets. Ministers from throughout the city joined her on air, with the exception of Rev. Albert Cleage who declined her invitation. Cleage declined WJLBs offer, telling his congregation “The radio station called me and asked if I wanted to issue a statement asking people to cool it. I said I had been trying to get white people to do something that would make it possible to cool it for years, and nobody had paid any attention, so I didn’t have any statements about cooling it now.”

In a sermon the first morning of the Rebellion Cleage compared the rebels in the street to Samson, and told his congregation that rebellions make strange heroes because, in rebellions, those who would normally be seen as hoodlums were doing “things which have to be done at a particular time in human history,” by standing up against oppressive forces. “There is some in good in what’s going on,” Cleage told his church, because the rebellion indicated that, “a whole lot of black people no longer believe that they ‘have a place.’”

At 8:54am on July 24, Milton Henry sent a telegram to Mayor Cavanagh from the Malcolm X Society stating eight demands upon which the end of the rebellion could be negotiated:

Regarding insurrection in Detroit, speaking for Malcolm X Society We will ask for cessation of all hostilities by insurrectionists

By seven PM today provided following eight points are accepted

- Withdraw all troops

- Release all prisoners

- Give amnesty to all insurrectionists

- Set up district police commissioners

- Agree to urban renewal veto by residents

- Divide city council and school board by districts

- Provide funds and community owned businesses

- Institute compensatory and compulsory equal employment enforcement.

Refusing to compromise with black radicals, the Mayor’s office did not respond to the telegram. Instead, they relied on force to try to re-establish order. Due to this violence, over the course of the rebellion, increasing numbers of black Detroiters began to believe that white power in the city was maintained primarily through brute force and consequently came to believe that only black power could stop white supremacy.

The more force the city’s police Department and the military used to restore order, the more willing black Detroiters became to meet the violence of the police with their own violence. Ed Vaughn encountered several people over the course of the rebellion committed to killing police officers and National Guardsmen who believed their actions were righteous and political. According to Vaughn, the work that Black Nationalist activists had been doing since the early 1960s was a critical component of the Rebellion’s impact on black critical self-consciousness. “It wasn’t black power that caused the rebellion,” said Vaughn. “People did not see any hope for themselves, people were beginning to be unemployed, we had no access to government, we were still pretty much confined to the ghetto, and then our consciousness was being raised at the same time….”

Thanks to this consciousness raising, Vaughn believed, those who did the looting actually understood their actions as “taking.” According to Vaughn, those who were taking things from stores “felt they had been oppressed, that these things had been gained from them illegally in the first place, that prices were too high, that merchants were gouging the people in the community, and so they took it out on them.” He remembered coming across “a group of brothers,” “who said they were fed up and that they just didn’t want to live like they had lived before and every night went out with their guns and they shot at police, shot at National Guardsmen…. That was the way that they would strike back at the power structure.”

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967, East Lansing, MI, Michigan State University Press, 1989

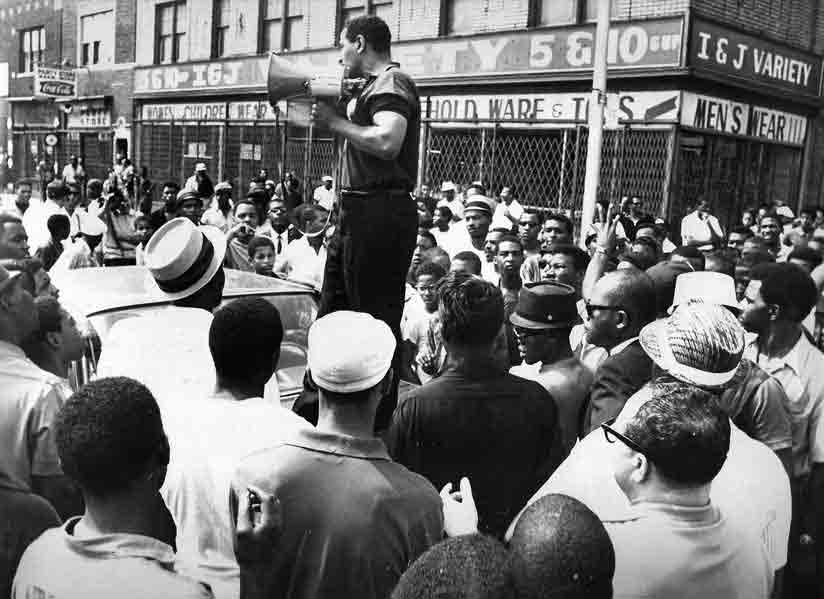

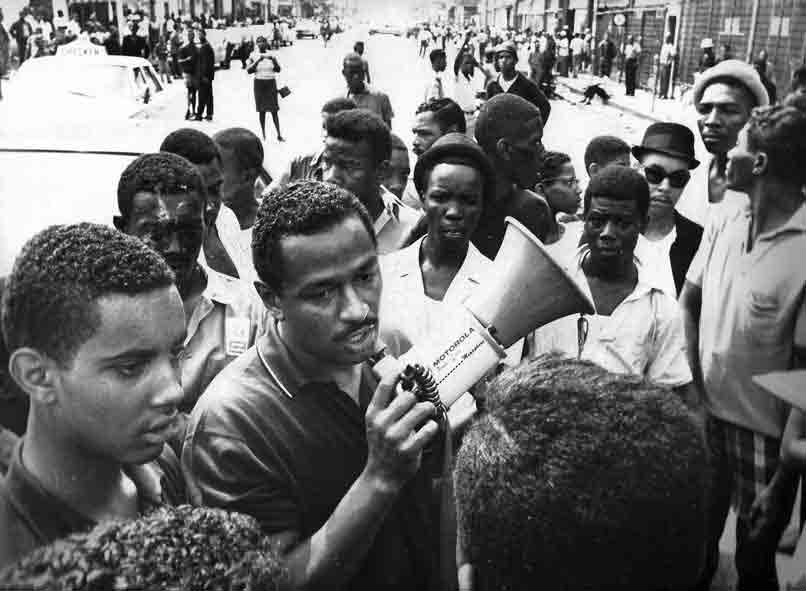

Local community, law enforcement, and political representatives meet on July 23, 1967 to develop a plan of action. At right, Representative John Conyers takes the podium. At far left is State Civil Rights Commissioner Damon Keith.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he explains the mood and actions of Detroit’s Black community during the 1967 Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

U.S. Congressman John Conyers addresses the crowd on 12th Street in an attempt to stop destruction in the city. Conyers, who represented Virginia Park’s district, was one of dozens of local and statewide political, civic, religious, and civil rights leaders in the streets trying to broker peace with demonstrators.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A man, recently emerged from a parked car on Blaine, is stopped before entering his apartment building on the corner of Blaine and Byron, the entrance to the Kiefer Hospital command post. Officers searched the man in hopes of finding evidence from an earlier sniper attack but found nothing.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

During many of the urban rebellions of the 1960s, businesses that treated Black customers unfairly became targets for looting, vandalism, or arson. As Ed Vaughn describes, people that engaged in such actions were usually not members of civil rights organizations, but saw their actions as retaliation for years and decades of racial, economic, and social injustice and oppression. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Daisy Nunley, in which she describes why certain stores were looted during the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. During many of the urban rebellions of the 1960s, businesses that were known to exploit or discriminate against Black customers became targets for looting, vandalism, or arson, while most Black-owned businesses and others that treated their Black customers fairly were generally left alone. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he describes the actions of police and civil rights leaders during the second day of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Rep. John Conyers tries, in vain, to get the attention of the crowds around him as he implores for a peaceful resolution during the first day of the unrest. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Herb Boyd, in which he describes witnessing the first day of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries