Interpretations

There are two broad interpretations of what happened in Detroit the week of July 23 1967. To some, what occurred that week was a “riot” that resulted in chaos and destruction, ultimately facilitating the decline of Detroit. To others, it was a righteous uprising or “rebellion” of black people, tired of racial oppression, unable to have their long-standing complaints addressed, and struck out in the only way available to them. The choice to use the terms riot or rebellion can usually tell you how the speaker interprets the events.

People who use the term “riot” often downplay any grievances on the behalf of black Detroiters and sometimes portray white people as victims of the events. For example, Mary Petlewski, who attended the University of Detroit in the summer of 1963, believes black Detroiters selfishly took advantage of low manpower amongst police. “I saw it at the time as a riot taking advantage of the situation. An escalation where it turned it from a very small confrontation that then escalated into everybody having a chance to just let their feelings loose and I don’t necessarily believe that everybody who rioted had a grievance. I think at that point it was just a big free-for-all and until people started getting killed, I think then it turned into something a lot more serious but I think that first day, maybe day and a half, when you could just run into a store and grab stuff, that was just kind of insanity.”

Ophelia Northcross, a registered nurse in the summer of 1967 and a resident of Boston-Edison, believes that the events were planned and aimed to take revenge on white business owners. “I mean, the riot had its own intent. And it was a national thing. And they struck each city, and although it was supposed to not be planned, it was planned. And when they struck Twelfth Street, they intended it to strike the downtown areas where the Jewish people owned all the businesses and had control of all the money, and that’s what they burned down. So they would go through and mark the black-owned businesses, and they would burn down a store next door to a black business, and only by accident would they burn a black business.”

In contrast, Wallace Crawford, who was a teenager in 1967 and became a police officer as an adult called the events of July 1967 a rebellion. “The other thing too, it wasn’t a race riot. It was like a rebellion. Because you had blacks and whites that was looting and that was doing things. It wasn’t like black people was trying to hurt white people, white people trying to hurt black people. It was looting.”

Joyce Ross, who was twenty-seven and living in Detroit that summer, saw the events as a political rebellion, “because I think people were pushed, they were suppressed, and I think it could happen again. Not necessarily with the black culture, just, I don’t think I want to get into the political thing, but…I do think that with the current administration that we have in Washington, I think it has created hatred between different groups. I mean, obviously. I mean, maybe that’s why I think it could happen again, but again, not just necessarily the blacks. It could be the Muslims.”

Ron Lockett, who was an activist in the wake of July 1967, takes a middle road. “You know, I think I could say riot slash rebellion. Because there was some horrendous treatment that was occurring. There was also some treatment by shop-owners who were selling bad meat, pawn shops that were doing, you know, usurious rates of interest. Now, does that mean that someone needs to have their property stolen and burned down? Absolutely not. But, you know, the treatment, and people not able to get jobs—and it was really starting to change in the auto industry at that particular time, too.”

The ways that people describe the events not only indicate how they interpret them but also indicate the approach they took to the city afterwards. Both Northcross and Petlewski left Detroit shortly after July 1967 and see very little hope for Detroit in the future. In contrast, both Ross and Lockett stayed in the city and committed to it.

References

Interviews with Ron Lockett, Joyce Ross, Wallace Crawford, Ophelia Northcross, and Mary Petlewski all conducted by Detroit Historical Society. All available at, https://detroit1967.detroithistorical.org/items/browse

President Johnson’s July 27, 1967 address to the nation regarding civil disorders in Detroit and Newark. Johnson describes his plans for new “riot control” measures, announces the formation of the Kerner Commission, and describes the “long-range solutions” to combatting the “conditions that breed despair and violence.” — Credit: LBJ Presidential Library

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee criticizes local, state, and national administrators for failing to understand and tackle the causes of the 1967 rebellion. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Herb Boyd, in which he discusses rumors that the 1967 Detroit Rebellion was planned. During many of the urban rebellions of the 1960s, rumors spread that the disorders were instigated by “outside agitators” who had incited Black communities to “riot.” No evidence has ever been produced to support such rumors.

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he explains the causes of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

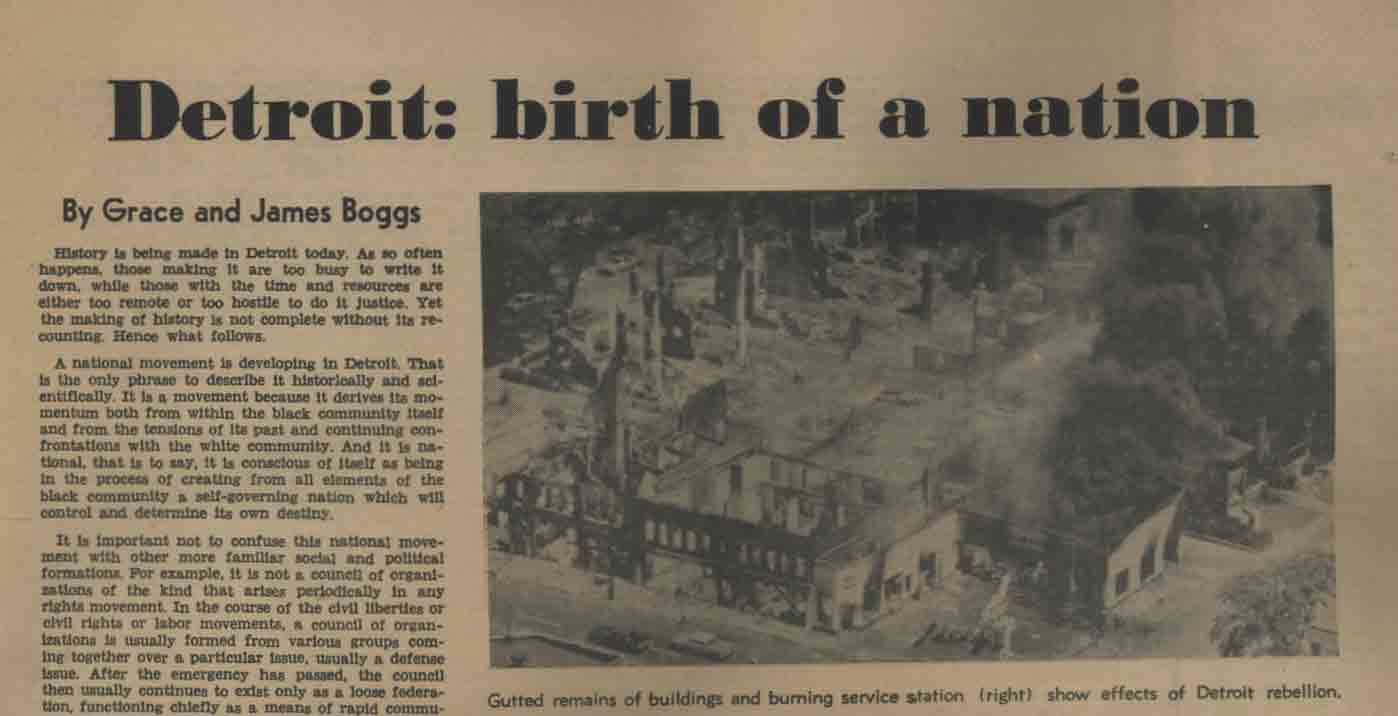

Article by Grace and James Boggs on the movement developing during the aftermath of the Detroit rebellion (National Guardian, October 7, 1967). –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Memoranda from Harold J. Bellamy to Richard Strichartz summarizing several social and demographic studies for the City of Detroit Mayor’s Committee for Community Renewal.. A notable contribution is a 1964 study conducted by Greenleigh Associates.– Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he explains the federal government’s perception of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion as a subversive plot. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

President Johnson’s July 24, 1967 address to the nation regarding civil disorder in Detroit and Newark. President Johnson focuses his address mainly upon “law and order” and acts of “violence” and “lawlessness” during the rebellions. — Credit: LBJ Presidential Library

Clip from a 1988 interview with former US Assistant Attorney General Roger Wilkins, in which he discusses President Lyndon Johnson’s reaction to the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, commonly known as the Kerner Commission. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Mayor Cavanagh’s recommendations after the 1967 rebellion included federal assistance for riot police, reparations, and making the needs of cities a national priority (August 15, 1967). — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University