Prediction

Because the police successfully quelled the disturbance on Kercheval, the city and the nation believed that Detroit had its racial problem under control. As Time reported, Detroit was the city in which no one believed the kinds of urban uprisings would occur that happened Harlem, Philadelphia, and Rochester in 1964, in Watts in 1965, and a host of cities in 1966.

Under Mayor Jerome Cavanagh, Detroit had become a model city in the eyes of some. Since his inauguration in 1962, the city had been awarded $42 million in federal poverty program funds and budgeted to spend $30 million in 1967 alone. $10 million of this budget was designated for job training and placement programs for unskilled and illiterate Detroiters. In just the summer of 1967 the city spent $3 million on recreation programs for young Detroiters. In 1967, 40% of black adults in Detroit owned homes and from 1960 to 1967 black unemployment decreased from over 10% to 6%. Based on these economic grounds, it was easy to believe that black Detroiters lived lives that were improving and had very little reason to rebel.

Despite this economic reality, black Detroiters still felt they had several things to be angry about. “The police have been fucking the people too damn long,” one black man told a reporter after the Kercheval Incident. “Everybody’s working around here that wants to work, so that’s not the problem. But you get through working and come home and there’s nothing else to do, so you go outside and [the police] chase you off your own streets,” said another. It was also common to hear poor blacks that had been victims of urban renewal consistently complain about being overcharged and cheated by white storeowners.

Taking account of these contradicting economic and social developments, Ron Scott explained that many black Detroiters experienced frustration primarily about their lack of power in Detroit and in their daily lives. “I would say, even though there was money, there was not power. There was access to the purchase of goods, but certainly not influence in the day to day political life of the city and that is what prompted what might have been felt by people hanging out on 12th street, hustling or whether it was people in the shops or whatever, it was all realized that none of us had the power to control our own destiny and had the ability to determine what was gonna happen to black folks. In other words, you could have a great job but you could be thrown out on the street and beaten to death by a police officer.”

In July of 1967, black Detroiters were frustrated because they believed they were equal to whites but lived in a city that treated them as second-class citizens. On July 23, 1967, this frustration bubbled over when police raided an afterhours bar, commonly known in Detroit as “blind pigs.” Despite being a rather routine occurrence, the raid sparked the longest outbreak of civil disturbance in US history. Unlike previous uprisings in Detroit, in just one week this outburst would convince more black people of the need for and possibility of black power more quickly than any activists could have dreamed.

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Max Herman, Summer of Rage: An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots, New York Peter Lang, 2013

Clip from a 1988 interview with former US Assistant Attorney General Roger Wilkins, in which he explains the connection between the Civil Rights Movement and the urban rebellions of the 1960s. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

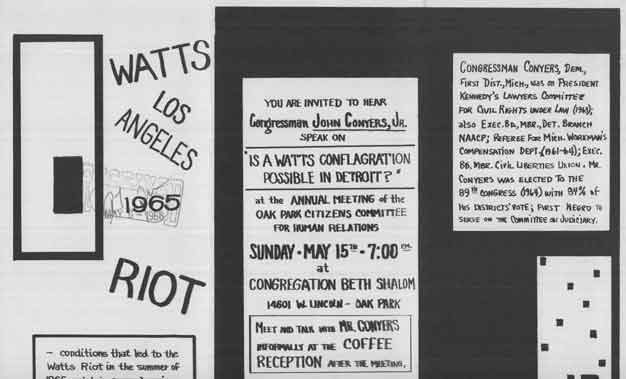

Pamphlet invitation, Watts Los Angeles 1965 Riot. “Is a Watts Conflagration Possible in Detroit?” Talk by Congressman John Conyers, Jr. at the annual meeting of the Oak Park Citizens Committee for Human Relations, May 15, 1966. Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

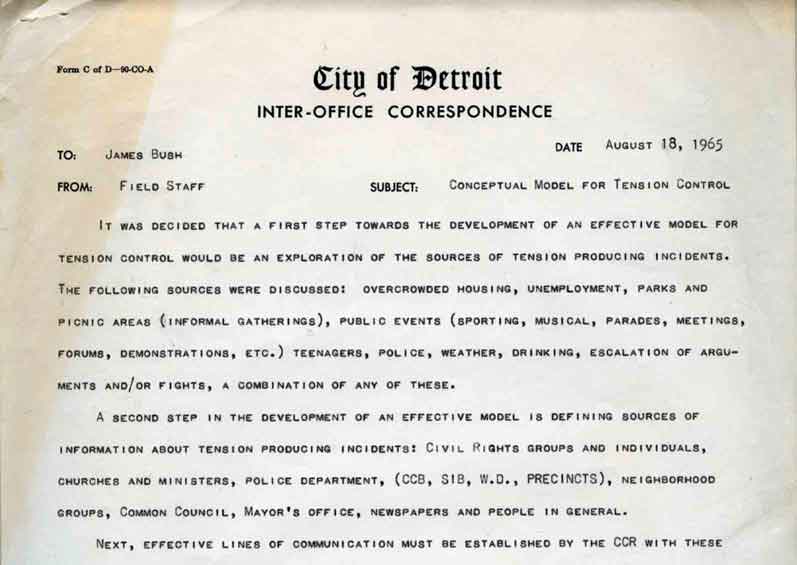

A memo from the Detroit Commission on Community Relations field staff to James Bush identifies sources of community tension and suggests methods of sharing information to prevent further incidents. August 18, 1965. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he describes the underlying causes of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

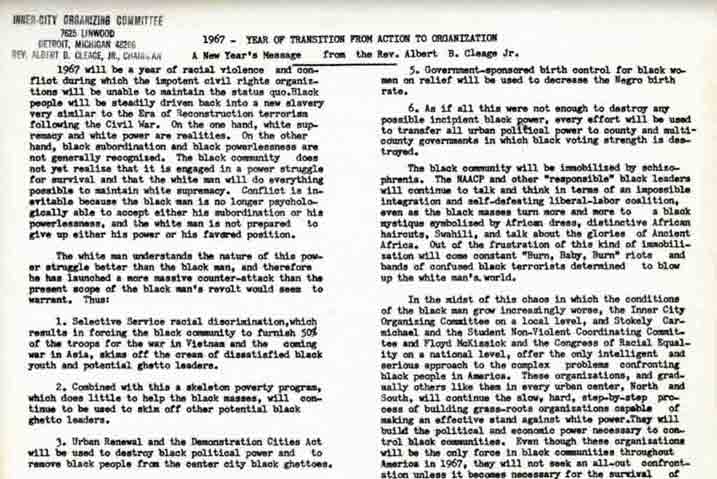

1967: Year of Transition from Action to Organization: A New Year’s Message from the Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr., chairman of the Inner City Organizing Committee. Cleage predicts, “1967 will be a year of racial violence and conflict…” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 2018 interview with Detroit attorney Elliott Hall, in which he explains the role of the police in the outbreak of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Detroit News article, “Detroit Policemen Train for Riot Prevention” by John W. Hushen, June 22, 1965. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

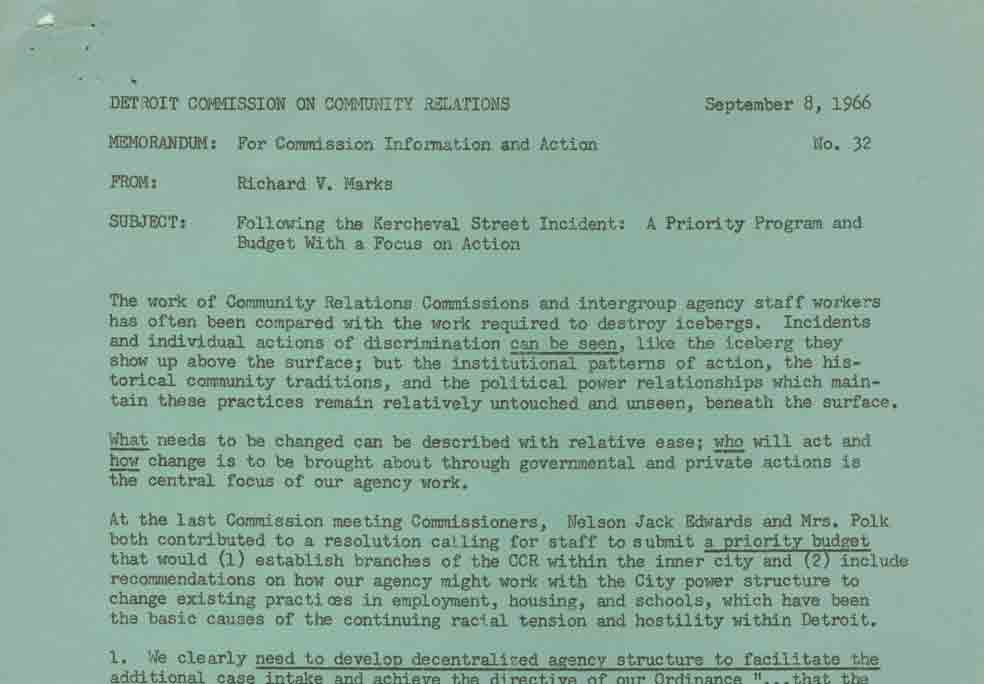

A memo from Richard Marks of the Detroit Commission on Community Relations proposes a priority program and budget to effect institutional change within the Commission and the City of Detroit following an August 9, 1966 confrontation between Black residents and police on Kercheval Street. September 8, 1966.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

A page from the The Michigan Chronicle, Detroit’s major Black newspaper, describes the mood on Kercheval Street following an uprising there. August 20, 1966.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

![Progress Report on [Police] Recruiting Progress Report on [Police] Recruiting](https://riseupdetroit.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Progress-Report-on-Police-Recruiting.jpg)

The Detroit Commission on Community Relations Subcommittee on Police-Community Relations provides an overview of recruitment reforms via meeting minutes. October 10, 1966.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

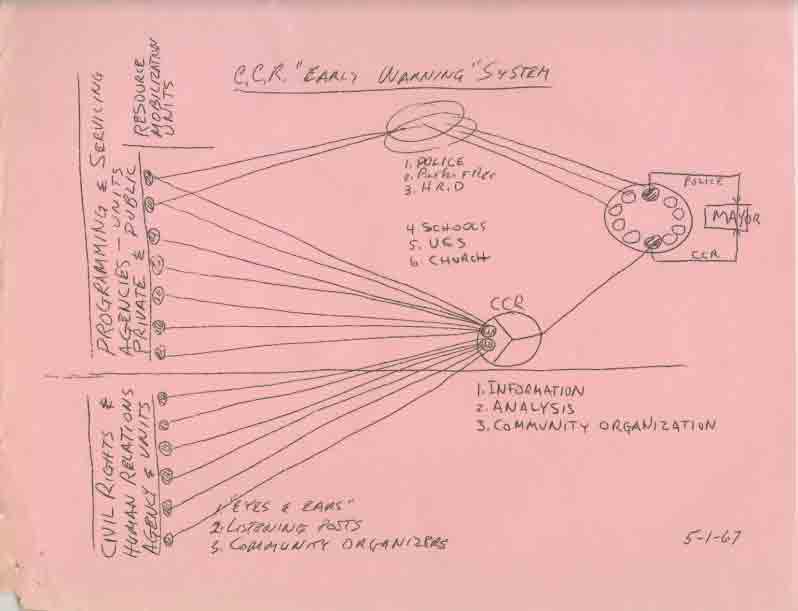

A sketch outlining a proposed “early warning” system for the Detroit Commission on Community Relations to identify areas of potential civil unrest in the city. May 1, 1967.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.