The Spark

Because of its three-shift industrial culture, Detroit had a culture of afterhours bars. While state laws mandated that bars close at 2:00am, second shift workers—and people who wanted to drink after 2:00—frequented afterhours bars locally referred to as “blind pigs.” Because they were illegal, police regularly raided them and customers were well aware the risk they took by drinking in these establishments.

Early on Sunday morning, July 23 1967, in contrast to the average blind pig which may have had twenty patrons, over eighty black people were celebrating the return of two GIs from Vietnam at a blind pig on the corner of 12th and Clairmount, on Detroit’s near west side. When police raided just before 4:00 am, they had no reason to expect any exceptional outcome.

However, on this particular night at this particular time, police lacked the power to quell what became a breakdown of black people’s willingness to tolerate their powerlessness. According to John Nichols, then Deputy Superintendent of the Detroit Police department (DPD), that night only six officers were on duty in the precinct where the blind pig was located and there were only forty-four department personnel city-wide committed to riot duty. Low on manpower and faced with choosing between just telling patrons to disperse and arresting them, police decided to shuttle patrons from the bar to jail. As the shuttle went back and forth, residents of 12th street gathered in the streets similar to the way 100 or so had gathered at the site of the Kercheval incident a year prior.

Similar to the Kercheval incident, the approximately 200 who gathered at 12th and Clairmount began throwing things at police officers, injuring a lieutenant, and breaking store windows. However, unlike the Kercheval incident a year prior, the backup of the Tactical Unit Squad was not available. That squad had ended its shift at 3:00 am leaving only 193 police officers on duty throughout the entire city. Because it was custom for off-duty officers to spend early Sunday mornings either fishing or with family, away from the phone, when residents of 12th St began looting pawnshops, no emergency backup was available. As the activities spread, the media began to report news of a riot.

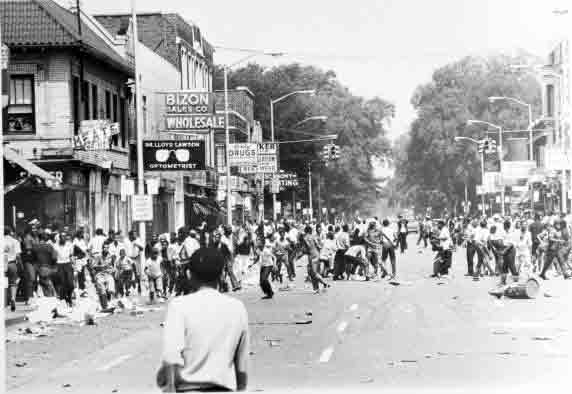

Without police backup the rebellion spread quickly. By 10:30 am there were thousands of people at the intersection on 12th and Clairmount, some of who had begun looting stores and setting fire to buildings. By 3:00 pm the looting had spread southwest to an A&P grocery store. Although black power activists succeeded in some cases in stopping people from lighting fire to buildings, the number of people looting constantly grew. It was impossible for them to control the crowd. When firefighters appeared on the scene to control fires they were often struck with bricks and bottles. Leaving the scene, by 3:00 pm huge swaths of the west side of Detroit were on fire.

As Herb Boyd described the feelings and events, “The feeling in the streets at that time was a kind of sense of euphoria, you know; a sense of freedom and rebellion. And the kind of excitement that was like touching everybody. Everybody felt like unified that you know the revolution was right around the corner. Because we had been talking about those things in the community anyway. So everybody felt that this was the catalyst. This was the charge. This was the igniter. This is what we’ve been waiting for. And so it was like a push. A march. People were just gathering all over the place.”

By 4:00 pm, mayor Cavanagh had contacted Gov. Romney and requested that the National Guard be sent to occupy Detroit. By midnight there were almost 900 guardsmen in the City. On the morning of the 24th Romney issued the guard to shoot any person looting.

Explaining to an interviewer how an event as mundane as a raid on a blind pig provoked a response so intense the National Guard was needed within twelve hours, Ron Scott described the raid like it was an accelerant for a fire. “Inside of most Black people there was a time bomb. There was a pot that was about to overflow, and there was rage that was about to come out. And the Rebellion, just provided an opportunity for that. I mean why else would people get upset about it, cops raiding a blind pig. They’ve done that numerous times before. But people just got tired, people just got tired of it. And it just exploded.”

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967, East Lansing, MI, Michigan State University Press, 1989

Max Herman, Summer of Rage: An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots, New York Peter Lang, 2013

Exterior view of the 12th Street building that housed Economy Printing and United Community League for Civic Action. The “blind pig,” whose raid sparked the beginning of the unrest, was located in the upper floor. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 2018 interview with Detroit attorney Elliott Hall, in which he explains the role of the police in the outbreak of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Herb Boyd, in which he describes witnessing the first day of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Watch this clip from WWJ-TV’s special report “Six Days in July” to see footage of press conferences held by Mayor Jerome Cavanagh and Governor George Romney in response to the outbreak of the rebellion. –Credit: https://www.clickondetroit.com/1967-detroit-riots

Clip from a 1988 interview with Detroit activist Ron Scott, in which he explains the underlying causes of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Explore The Archives

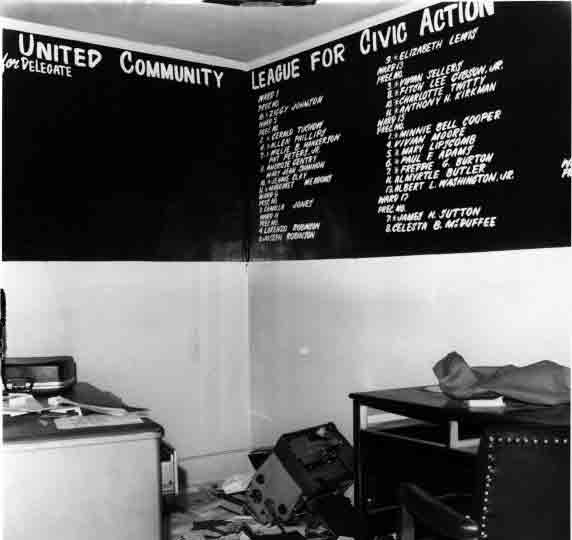

Interior view of the United Community League for Civil Action, the Blind Pig at 9125 12th St. where the Civil Unrest of 1967 began. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Helen Kelly, in which she recalls learning of the outbreak of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. In this clip, Kelly describes her fears as a mother during the rebellion and the actions of the National Guard. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

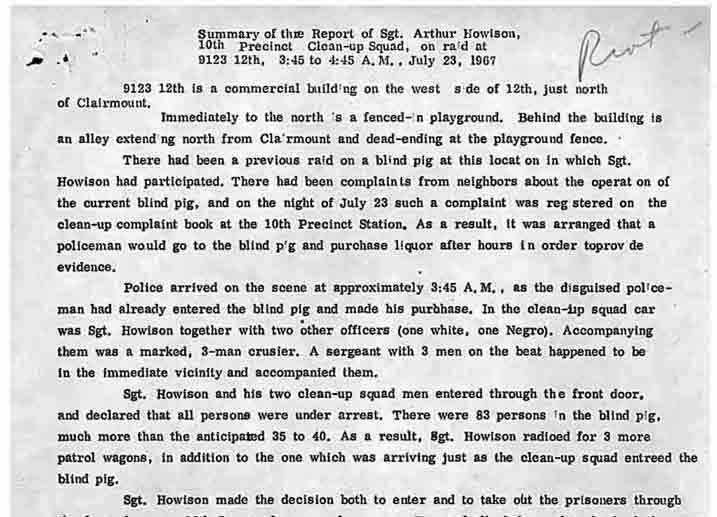

A Detroit Police Department summary of the raid of the blind pig on 12th Street, based on reports by Sgt. Arthur Howison. Howison was a member of the 10th Precinct’s “Clean-Up Squad,” which was responsible for policing minor crimes and vice in the city. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

“Former Detroit Police officer Anthony Fierimonte discusses his experiences on the force–including his role in the raid on the blind pig at 12th Street and Clairmont Street on July 23, 1967–in this interview conducted on October 10, 2014.” –Credit: Detroit Historical Society

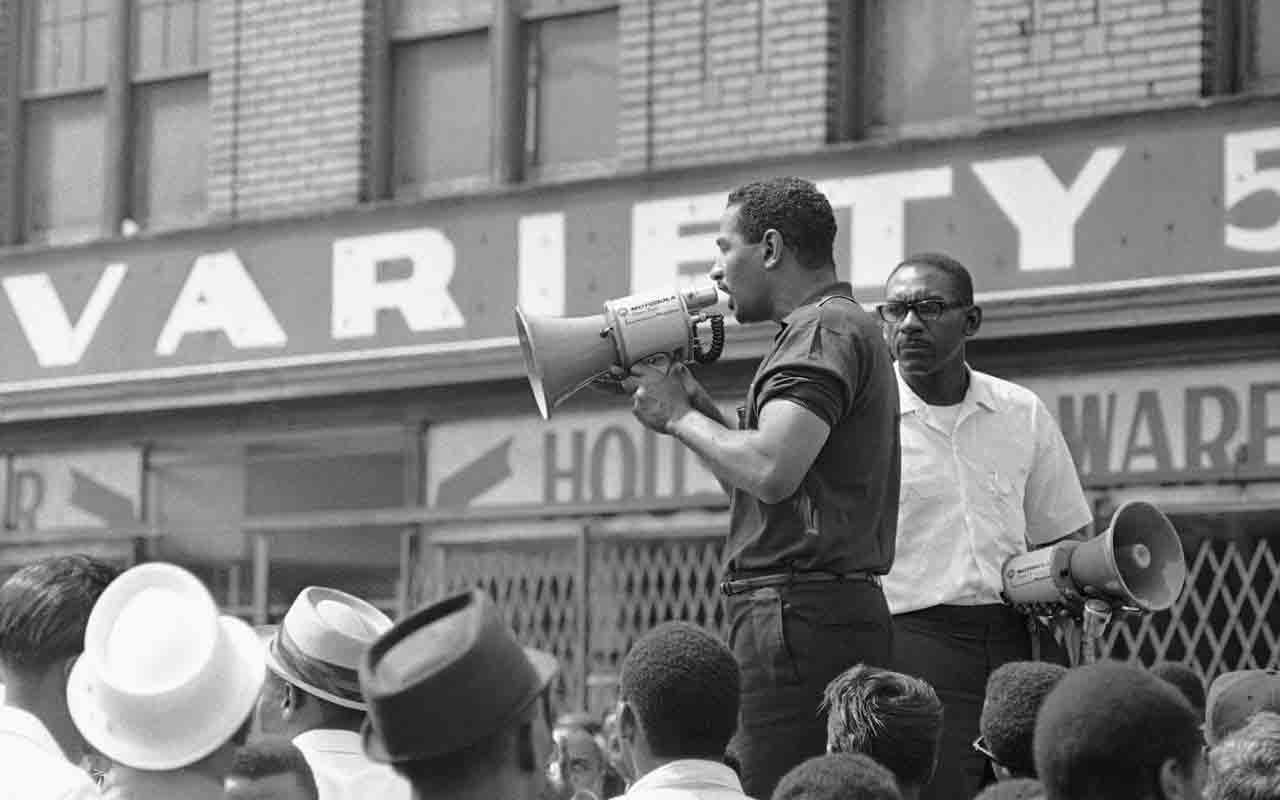

U.S. Congressman John Conyers addresses the crowd on 12th Street in an attempt to stop destruction in the city. Conyers, who represented Virginia Park’s district, was one of dozens of local and statewide political, civic, religious, and civil rights leaders in the streets trying to broker peace with demonstrators. –Credit: Ebony

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he describes police actions and start of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A bird’s-eye view of 12th Street during the first day of the 1967 Civil Unrest. “Black Power” is painted in the center of the street. The Chit Chat Lounge is in view at upper, right corner. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Herb Boyd, in which he describes the police raid on a “Blind Pig” that sparked the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. As Boyd and others explain, after-hours nightclubs in Detroit, known as “blind pigs,” were frequently targeted by police raids in the mid-1960s, but this particular raid triggered much stronger reaction because it was during a homecoming party for Black veterans of the Vietnam War.

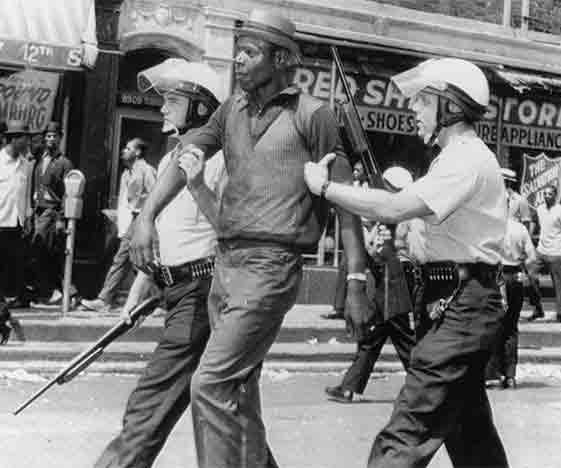

Detroit police officers in riot gear detain an African American man who they accused of looting shortly after the “blind pig” was raided on 12th Street on July 23, 1967. –Credit: New York Post

Martha Reeves, lead singer of the Motown group Martha and the Vandellas, recounts learning of the start of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion on July 23rd while on stage at the Fox Theatre. Watch the interview to hear Reeves’ recollections of that night, her explanation of what caused the rebellion, and the roles of the Detroit Police Department in the city’s Black community. — Credit: Detroit Historical Society, Detroit 1967 Online Archive

12th Street descends into chaos on the first day of the Civil Unrest of 1967. At rear, center, the Blind Pig, whose raid by police officers sparked the conflict, can be seen behind the Economy Printing sign. In the distance a photographer snaps pictures of the scene. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

“This WWJ-TV (which later became WDIV) special titled “Six Days in July” focuses on the coverage of the 1967 riots in Detroit and the response from officials and the community.” Watch this clip to see footage of the outbreak of the rebellion and learn how reporters and journalists described the events that took place. –Credit: https://www.clickondetroit.com/1967-detroit-riots

Governor George Romney and Detroit Mayor Jerome Cavanagh watch events unfold “in the field,” likely from the grounds of Southeastern High School. — Credit: Detroit Free Press

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident and owner of Vaughn’s Bookstore, Ed Vaughn, in which he recalls the outbreak of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. Though Vaughn was on his way back from the National Conference on Black Power in Newark when the rebellion began, he was not surprised when he heard about it over the car radio. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Looking back almost 50 years later, Detroit resident Charlie Beckham discusses the underlying causes and outbreak of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. — Credit: Detroit Historical Society, Detroit 1967 Online Archive

Detroit resident Conrad Mallett, Jr. remembers being on 12th Street shortly after the 1967 Detroit Rebellion broke out on July 23, 1967. Watch the interview to learn about how Mallet remembers the events outside the blind pig on 12th Street, which he observed as a teenage paperboy. — Credit: Detroit Historical Society, Detroit 1967 Online Archive