Labor Organizing

and the Revolutionary Union Movements

According to activist General Baker, during the rebellion, “If you got sick you couldn’t go the hospital. If you got hungry, you couldn’t go buy no food. But if you had a badge from Chrysler, Ford, or General Motors, you could get through all the police lines and all the army lines, and take your butt to work.” From this relationship to martial law, black workers in Detroit concluded, according to General Baker, that the only place young blacks “had any value was at the point of production.” This knowledge of where blacks were valued contributed to long developing conditions for increased militancy in Detroit auto plants by black workers.

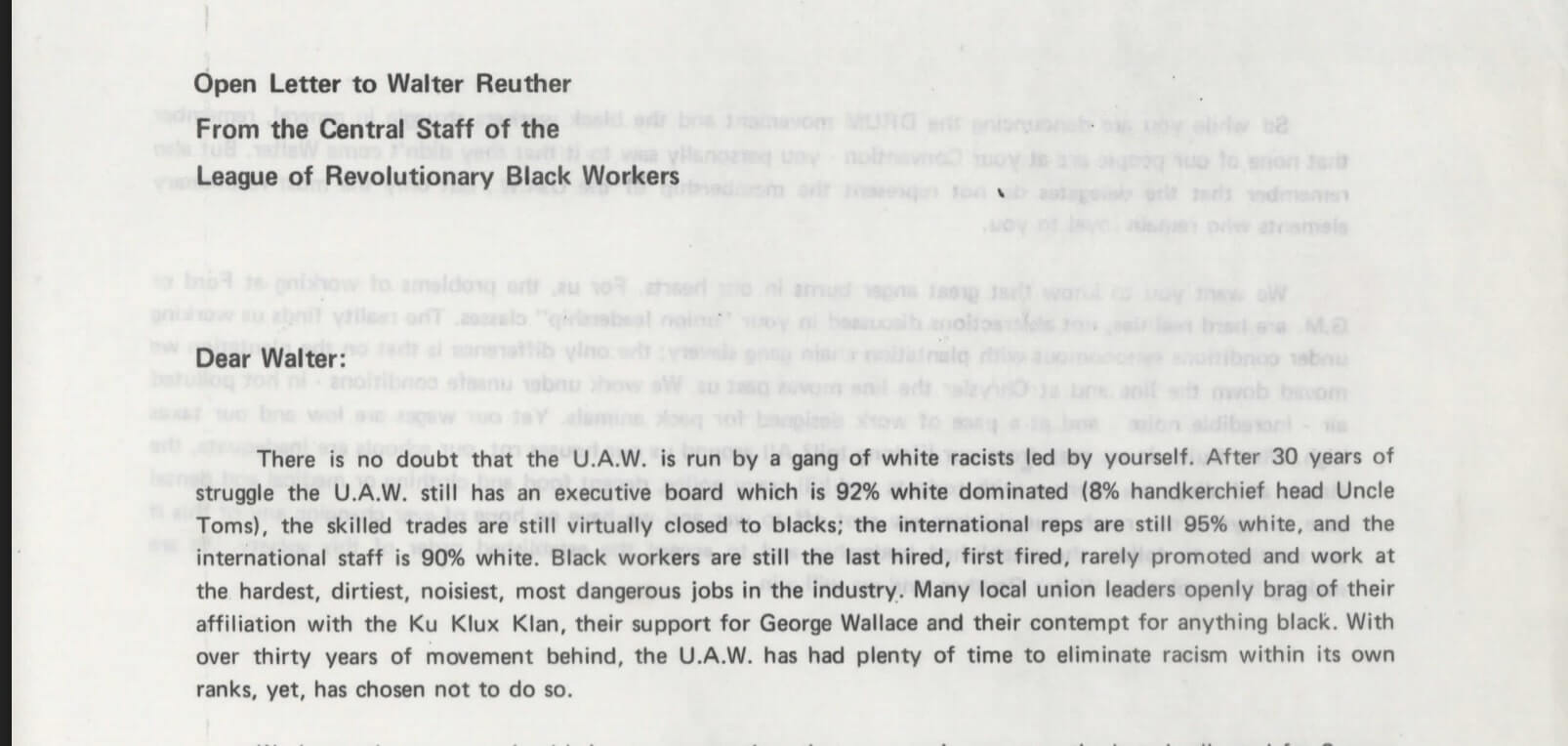

By 1967, 51 percent of all union autoworkers in Detroit rated the work of their Locals unsatisfactory and 44 percent also rated the work of the International unsatisfactory. Black workers were especially frustrated with the UAW over speedups and safety conditions. Because GM and Ford automated and relocated the majority of their plants outside of Detroit during the 1950s, black workers in Detroit were concentrated at Chrysler plants, many of which had not been updated since the 1940s. In order to keep pace with Ford and GM, Chrysler mandated overtime and sped its line up far beyond the agreement reached between the UAW and Chrysler in collective bargaining.

As Heather Thompson has noted, “Chrysler’s workers, particularly its black workers in the worst jobs, were strained both physically and emotionally. The faster the line ran, the more tired the workers became. The older and more decrepit the machinery, the more auto jobs became a health a safety hazard. Chrysler’s inadequate internal investment and managerial aggressiveness, along with its inhumane overtime demands, contributed to the hazardous conditions that increasingly made the life of black workers in particular, but all workers to a great extent, hard to bear.”

With the UAW exhibiting little willingness to hold Chrysler accountable for its working conditions and the needs of its black members, black workers made little distinction between the company and the union. As one black worker told journalist William Serrin, “‘we’re still on the plantation. That’s what the plant is—short for plantation.’ ‘Nobody does anything for us—not the companies, not the union.’”

Following a spontaneous walkout after Martin Luther King’s assassination, black workers unleashed a set of wildcat strikes in Chrysler plants that gave rise to the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM).

On May 2, 1968 two white women stood at the plant gates of Dodge Main following lunch and, in protest of a speedup, refused to go back in. Several black workers joined them, and their activity created an integrated, four thousand-person strike that shut Dodge Main down for the day. Although the picket line was thoroughly mixed, out of the seven workers fired in retaliation, five were black. The only two workers to not be rehired were also black, General Baker and Bennie Tate. Chuck Wooten and a few other black workers decided to respond. “We were sitting at that table talking and it was there we decided we would do something about organizing black workers to fight the racial discrimination inside the plants and the overall oppression of black workers. Well, this was something I’d been trying to get started for the four years I was in there, but I just never ran into anyone who was conscious enough to really take some steps about doing something about this. And this was the beginning of DRUM.”

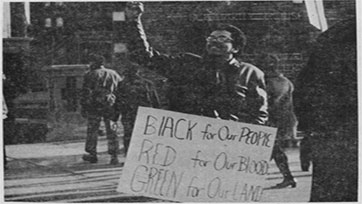

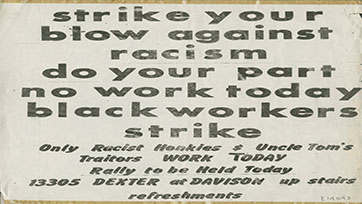

These workers then began meeting with the Inner City Voice (ICV) and producing a DRUM newsletter they distributed at Dodge Main to agitate and mobilize black workers. Within nine weeks of agitation, a unity developed amongst black workers at Dodge Main and they called a black only strike. DRUM demanded diversity in black employment, the right for black workers to cease paying union dues and direct those fees to black organizations, and demanded that black Chrysler employees in South Africa be paid equal to whites.

To prevent retaliation from the company the picket line was manned with ICV staff, students, intellectuals, and various community members. According to the Detroit Free Press, over three days DRUM succeeded in keeping approximately 70 percent of black workers out of the plant and prevented the production of an estimated 1,900 cars. Although none of DRUMs demands were met, the strike provided political education for blacks throughout the city because it demonstrated that black workers had the power to shut down whole factories. In the aftermath of the strike, workers at other plants also formed RUMs (Revolutionary Union Movements) and eventually led to the formation of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW).

Of the additional RUMs formed, the formation of Eldon Avenue Revolutionary Union Movement (ELRUM) played the biggest role in facilitating the emergence of the LRBW. According to the League, as the only plant in all of Chrysler’s operations that produced parts for every Chrysler car, Eldon Avenue Gear and Axle was a critical component in Chrysler’s production apparatus. Eldon had a higher percentage of black workers than Dodge Main and when ICV began producing an ELRUM newsletter they once again gathered a great deal of support from black workers. Following the same formula as DRUM, a strike was called after nine weeks of agitation. 75 percent of the plant participated, completely shutting production down for the day. Unlike at Dodge Main where Chrysler did not punish workers, 26 workers were fired from Eldon, despite the fact that pickets were manned solely by students, intellectuals, community members, and previously fired workers from other plants.

The retaliation ELRUM experienced created the impetus to form the LRBW. As League officials told an interviewer, “We knew at that point that what we had to do was begin to organize workers in more plants and begin to organize the black community to relate to the struggle in the plants, in the city, in the state, and eventually around the country. That led to the formation of the League. Now the reason that was necessary was because it became clear that no single group of workers in a single plant can win a struggle for justice in a plant, in an isolated situation. The only way that these struggles can be won is through the support of workers in other plants and through support of the black community too. So we decided after the Eldon situation to set about organizing toward that end.” Shortly after the strike at ELRUM, the ICV developed the League of Revolutionary Black Workers subsuming ELRUM, DRUM, JARUM (Jefferson Avenue), CADRUM (Cadillac), FRUM (Ford), and other RUMs as components of the League.

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, Boston, South End Press, 1998

David M. Lewis-Colman, Race Against Liberalism: Black Workers and the UAW in Detroit, Urbana, University of Illinois Press

William Serrin, The company and the union: The ‘civilized relationship’ of the General Motors Corporation and the United Auto Workers, New York, Knopf, 1973

Heather Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City, Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2001

Chuck Wooten, “Why I Joined DRUM,” Philip S. Foner and Ronald L. Lewis, Black Workers: A Documentary History from Colonial Times to the Present, Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1989

A documentary film produced by journalist Gary Gilson about racial discrimination and exploitation in employment in Detroit after the 1967 Rebellion. Gilson filmed the documentary over a five-month period from 1968-1969. The film also contains important footage of conversations about racism and inequality in post-rebellion Detroit.

Finally Got the News was produced by the LRBW in 1970 to promote political consciousness about the roles of Black workers in the American economy and to recruit members to the League. Watch the film to hear Black workers talk about conditions in the automotive industry and learn about the origins, ideologies, and actions of the LRBW.

This edition of the Inner City Voice covers the genesis of the wildcat strikes at Chrysler in May 1968 that led to the formation of DRUM. The ICV was launched by General Baker, John Watson, Mike Hamlin, and Luke Tripp in September 1967 to cover issues of concern to Detroit\’s Black communities through a radical perspective. See page two for an open letter to Chrysler Corp from General Baker.

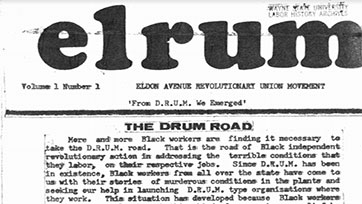

The first edition of the Dodge Revolutionary Movement Union\’s newsletter, drum. Check out this inaugural edition to learn about the May 1968 wildcat strikes and some of DRUM\’s grievances against Chrysler.

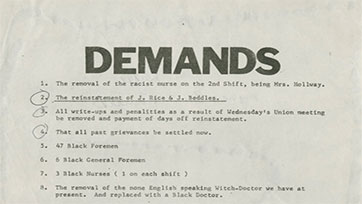

A leaflet for an August 1968 forum on DRUM at Eugene V. Debs Hall in Detroit. Check out the second page for a list of DRUM\’s 14 demands from Chrysler. How might the Black Power Movement have influenced these demands?

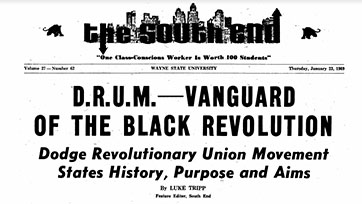

This edition of Wayne State University\’s student newspaper, The South End, covers the formation and early activities of ELRUM. Under the leadership of editor John Watson, The South End served as an important link between struggles for black empowerment and self-determination on and off-campus.

Compilation of oral history interviews of members of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, created by the League of Revolutionary Black Workers Media Project. For more interview footage and information about the LRBW, please visit https://www.revolutionaryblackworkers.org/

Explore The Archives

Clips from 2018 interviews with veteran Detroit activists Frank Joyce, Elliott Hall, and JoAnn Watson, in which they discuss the organizing, impacts, and legacies of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit. –Videography: 248 Pencils

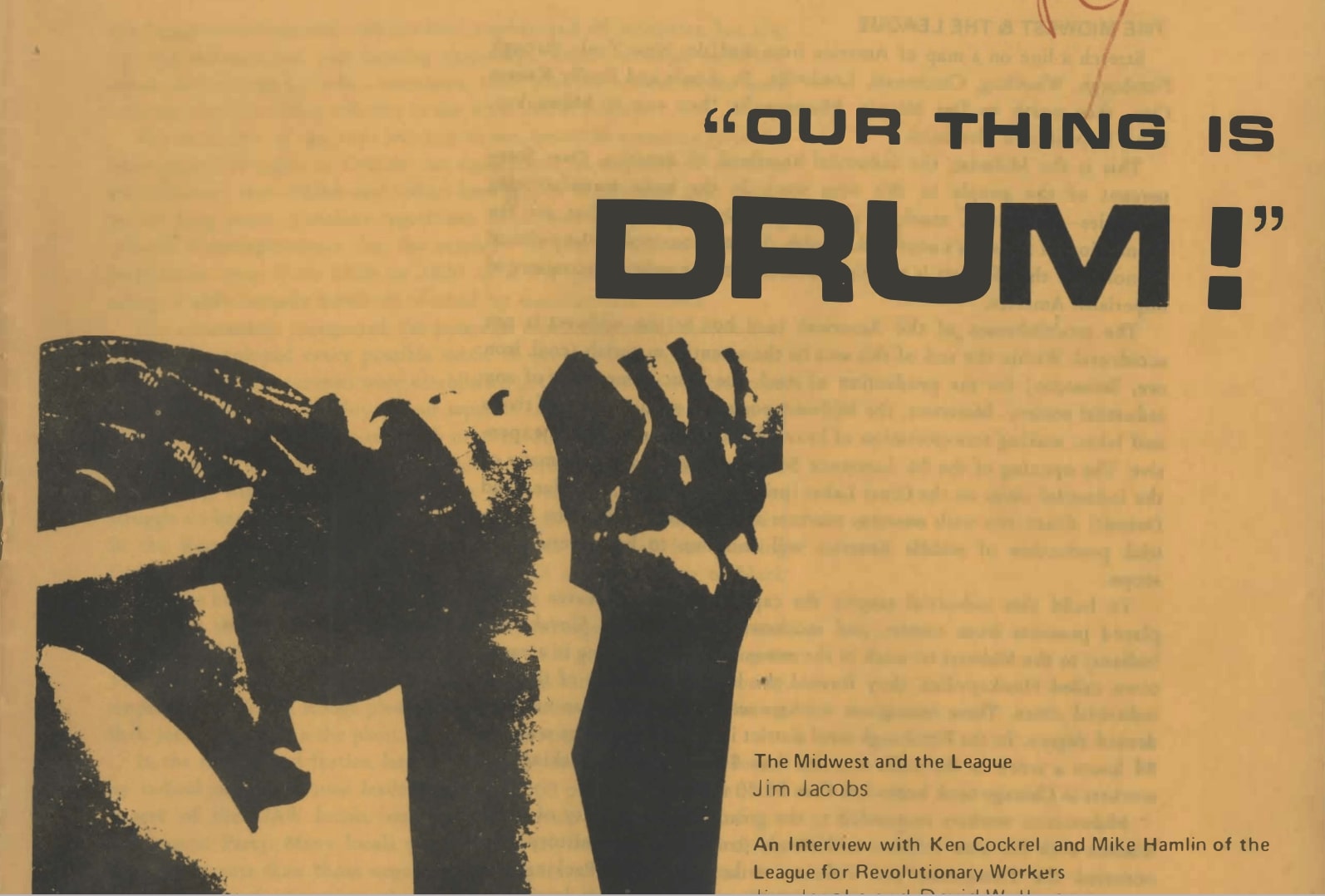

Our Thing Is DRUM! Booklet published by the New England Free Press on the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and the automobile industry. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

DRUM flyer for wildcat strike and rally in 1969. The wildcat strike, a strike undertaken by union workers without union authorization, became DRUM’s tool for addressing the grievances Black workers faced in Detroit’s factories. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University