The Election of

Coleman A. Young

In 1969, Richard Austin ran for mayor as the city’s first black candidate. Austin won the primary that year, defeating both white candidates who ran on platforms to “restore law and order” after the Rebellion. Despite his primary victory, Austin loss the general election when there were no longer two white law and order candidates to split the white conservative vote. However, because he lost by only 7,312 votes in a city that was still less than 50 percent black, black Detroiters and Detroit’s business and political class recognized that a black mayor in Detroit was inevitable and would most likely happen in the 1973 election. Coleman A. Young became the clear candidate that both of these groups would support.

Young emerged as the unique figure who could secure the votes of working class blacks as well as the city’s power elite because he had both a long history of speaking up against racism and a long record as an elected official who was not hostile to business. Young first gained prominence in 1952 when he appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee and told them, “I am not here to fight any un-American activities, because I consider the denial of the right to vote to large numbers of people all over the South un-American.” With this willingness to both stand up for black Americans and to stand up to the federal government, Young endeared himself to black Detroiters indefinitely.

With this appeal in Detroit’s black community, Young was able to build a strong electoral base. In 1961, he was elected as a Democratic candidate for the state’s constitutional convention, in 1964 he was elected to the Michigan State Senate, and in 1968 he became one of the first African-Americans on the Democratic National Convention. As State Senator, Young was instrumental in authoring and passing legislation for the decentralization of Detroit Public Schools and in struggling against funding discrepancies for rural and urban districts. His location in the mainstream of the left of the Democratic Party made him suitable to the city’s liberal power brokers and while it limited his appeal to the city’s black radical activists, his support for school decentralization and his history of activism endeared him to black power revolutionaries to some degree.

Running against former police chief John F. Nichols, the primary issues in the 1973 election became crime, police brutality, and the Detroit Police Department’s program STRESS. When the STRESS unit emerged in 1971, it was a response to the 23,000 reported robberies that occurred in 1970. However, because STRESS had limited impact on the robberies and greatly contributed to police brutality against blacks, Young was able to use the campaign to expose STRESS’s ineffectiveness and its brutality. Because Nichols was the architect of STRESS, Young was also able to put Nicholas on the defensive throughout the campaign.

While Young’s promise to end STRESS bolstered his support amongst blacks, in order to win he needed a large black turnout, which he got with the support of Rev. Albert Cleage. At the beginning of the campaign, Young approached Cleage who had played a major role in promoting to blacks the need for a black mayor and had long emphasized the political power of blacks. According to Aswaad Walker, “Young asked Cleage exactly what kind of on-the-ground organization did he need to win. Cleage’s response was the program he put into place, with campaign volunteers calling, visiting homes, and leafleting to explain to black Detroiters what was at stake in the 1973 mayoral election, and the process to ensure their votes counted. On election day, volunteers provided transportation to the polls for those in need, while others stationed outside voting locations passed out a slate of candidates approved as having the black community’s interests at heart.” Cleage’s organizing was so useful that he used the campaign to launch The Black Slate, Inc, a political action committee.

Thanks in large part to Cleage and the Black Slate’s support, Young won the election 233,674 votes to Nichol’s 216,933.

Upon his inauguration, Young famously told the city, “I issue open warnings now, to all dope pushers, to all rip-off artists, to all muggers, it’s time to leave Detroit; hit Eight Mile Road! And I don’t give a damn if they’re black or white, or if they wear Superfly suits or blue uniforms with silver badges; Hit the Road!” One of Young’s first acts as mayor was the elimination of STRESS. In an attempt to keep a promise to white voters that his administration would be 50 percent white, he kept on Philip Tannian as police chief but created the position of executive deputy chief of police, to which he appointed a black man, Frank Blount. In 1976 he appointed William Hart as the city’s first black Chief of Police. Young also implemented a system whereby for each white officer promoted, a black officer would also be promoted. In addition to changes in the police department, within Young’s first few years he appointed a black superintendent of schools and by 1977 city council was majority black and had a black president.

References

Heather Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City, Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2001

Aswaad Walker, Politics Is Sacred: The Activism of Albert B. Cleage, Albert Cleage Jr. and the Black Madonna and Child, New York, Palgrave, 2016

Clip from a 2018 interview with Detroit attorney Elliott Hall, in which he explains how politics in Detroit changed in the years following the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. –Videography: 248 Pencils

JoAnn Watson and Charles Ezra Ferrell discuss Coleman A. Young\’s organizing background in the post-war era. –Videography: 248 Pencils

A compilation of news footage covering the issues of STRESS and police reform during Detroit\’s 1973 Mayoral campaign. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

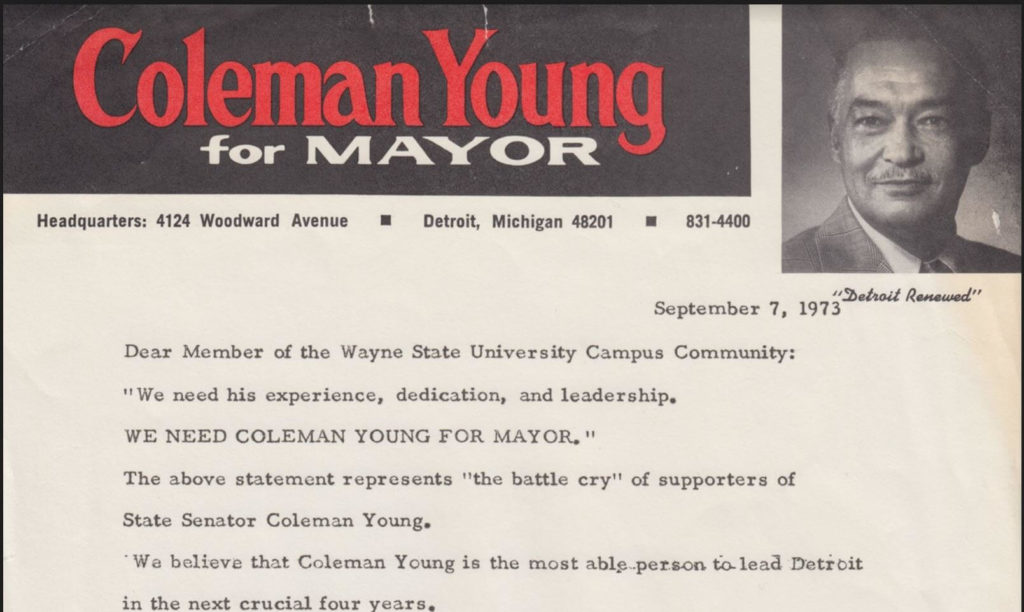

Poster from Coleman A. Young\’s 1973 campaign for Mayor of Detroit. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

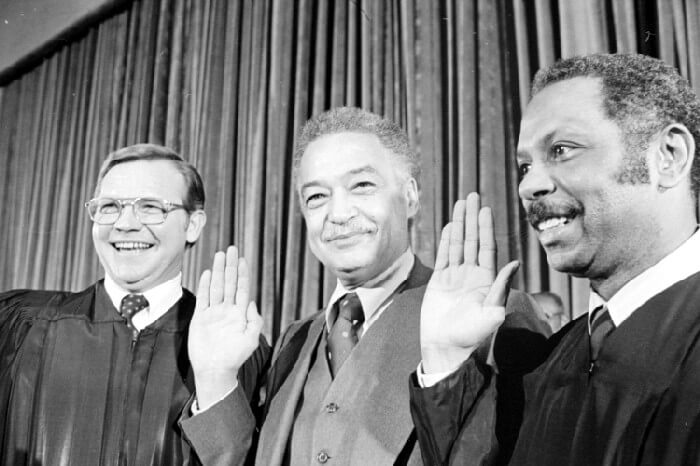

Coleman A. Young is sworn in as Detroit\’s first African American Mayor on January 2, 1974. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 2018 interview with Detroit attorney Elliott Hall, in which he discusses police reform in Detroit under Mayor Coleman A. Young. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Explore The Archives

This song, “Young Train,\” was performed by The Originals in support of Coleman Young’s mayoral campaign and issued as a promotional single by Motown Records in 1973. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

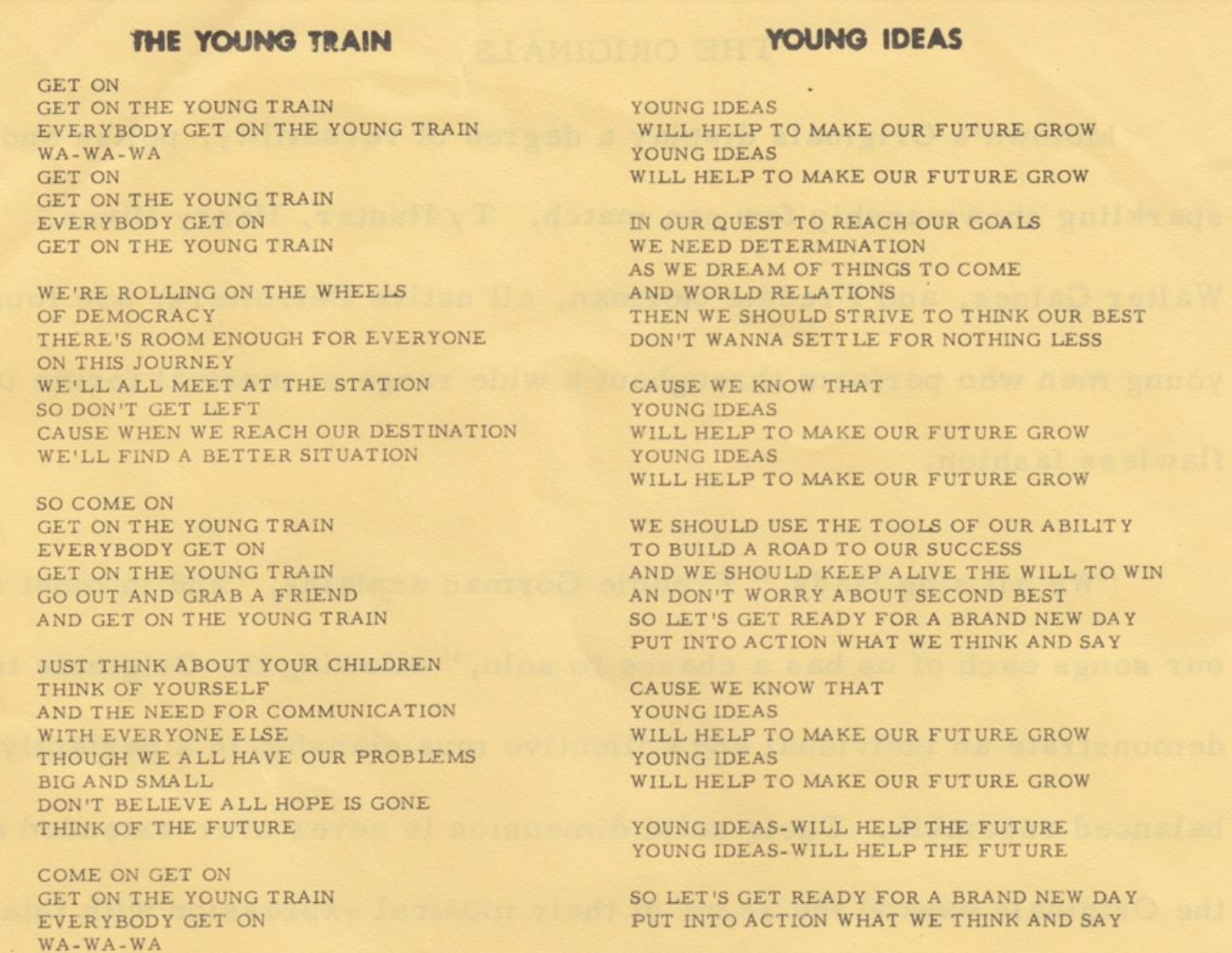

Lyrics to the songs \”The Young Train\” and \”Young Ideas,\” performed by The Originals in support of Coleman Young’s mayoral campaign and issued as promotional singles by Motown Records in 1973. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

This song, “Young Ideas,\” was performed by The Originals in support of Coleman Young’s mayoral campaign and issued as a promotional single by Motown Records in 1973. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) stand outside an unidentified building, possibly during an anti-war demonstration, and hold signs, that read: “The Yanks Are Not Coming–Let God Save the King!” and “No Jim Crow.\” Location is not identified, but is presumed to be Detroit, Michigan. Coleman A. Young is in the second row, second from right. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

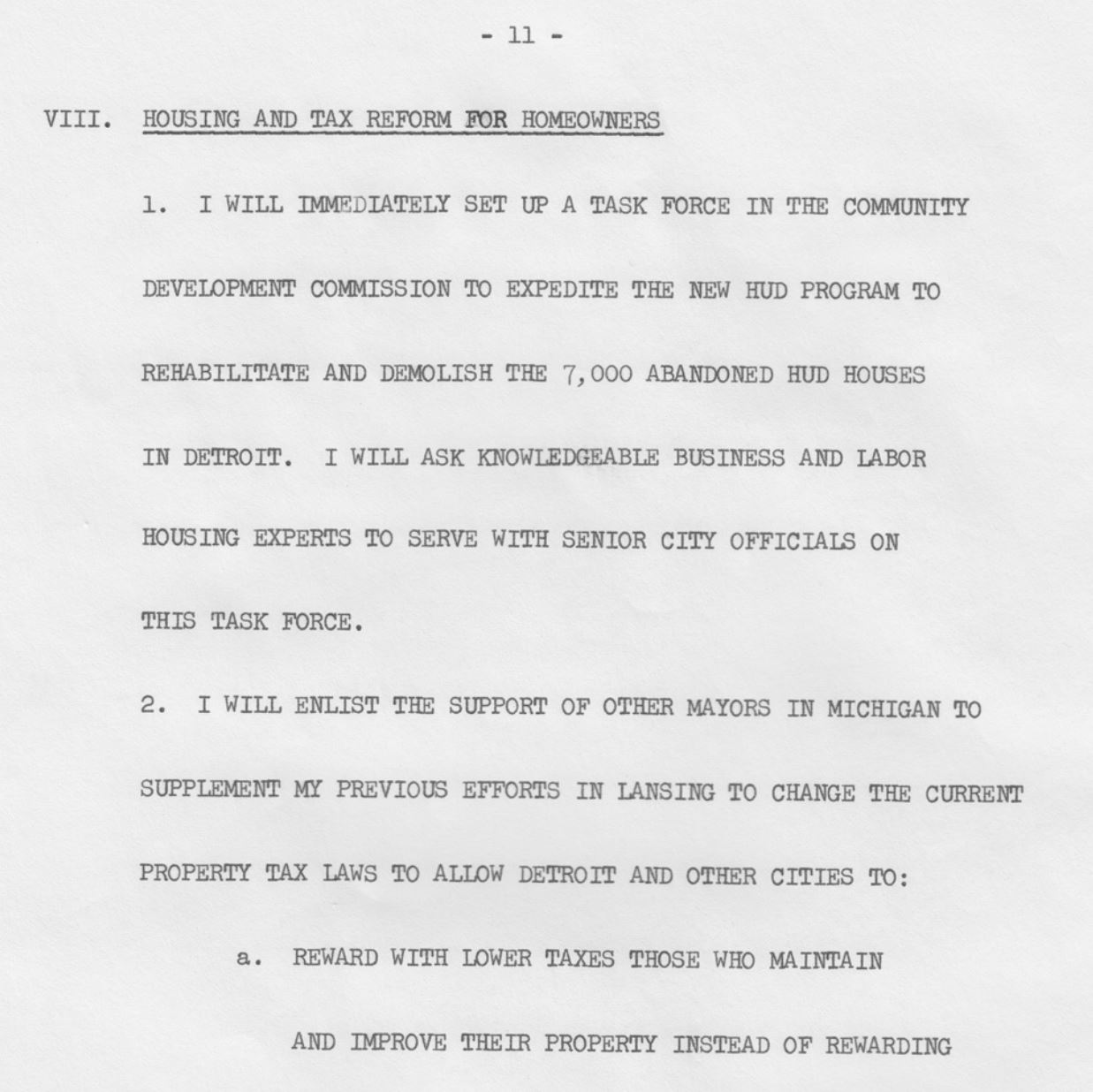

Coleman Young’s campaign positions on housing and homeownership from notes for a speech delivered at the Economic Club on October 29, 1973. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University