Great Migrations

After securing the right to vote in 1870, Black Detroiters spent the remainder of the 19th century trying to integrate into the larger city of Detroit. However, after being displaced in jobs in iron, lumber, tobacco, and shipping by European immigrants and continuously finding themselves unwelcomed by white Detroiters, Black Detroiters began to intentionally build community life amongst themselves around 1900. Led largely by Detroit’s Black middle class with deep historical roots in the city, groups like the Christian International Club and the Detroit Women’s Council made helping new migrants to the city part of their mission. Thanks to these organizations, when Detroit’s Black population increased from 5,741 to 40,838 between 1910-1920, migrants were provided with a safety net and way to adjust to living in Detroit.

Throughout the first quarter of the 20th century, Detroit’s Black population steadily grew, especially after 1915. By the summer of 1916, one thousand Black people were arriving in Detroit from the south per month. Then, from 1924-1925, an additional 40,000 Black people came to the city. Consequently, as of 1926, 85% of the city’s Black population had arrived in only the last ten years.

The Detroit branch of the National Urban League played a very important role in securing work for these new residents. In 1917 alone, the Urban League secured jobs for more than 10,000 Blacks, 80% of whom had in been in Detroit less than a year. Most of these newly employed Blacks were men who had left their families in the south to fulfill a demand for labor created by World War I in northern industry and to escape Jim Crow racism. After securing jobs, their families often joined them.

As this migration transformed the city, dances and parties for the city’s migrants hosted by the Urban League evolved into the Columbia Center in 1919. Quickly becoming a well-run community center, the Columbia Center had events for children, housed a training school for Black domestic workers, held music and art classes, had readings rooms for adults and children, hosted debating, literary, and social clubs, and generally became a place where new migrants socialized and built new lives for themselves. The Urban League also organized the Young Men’s Progressive Association, an organization especially devoted to preparing young Black men for college and athletics.

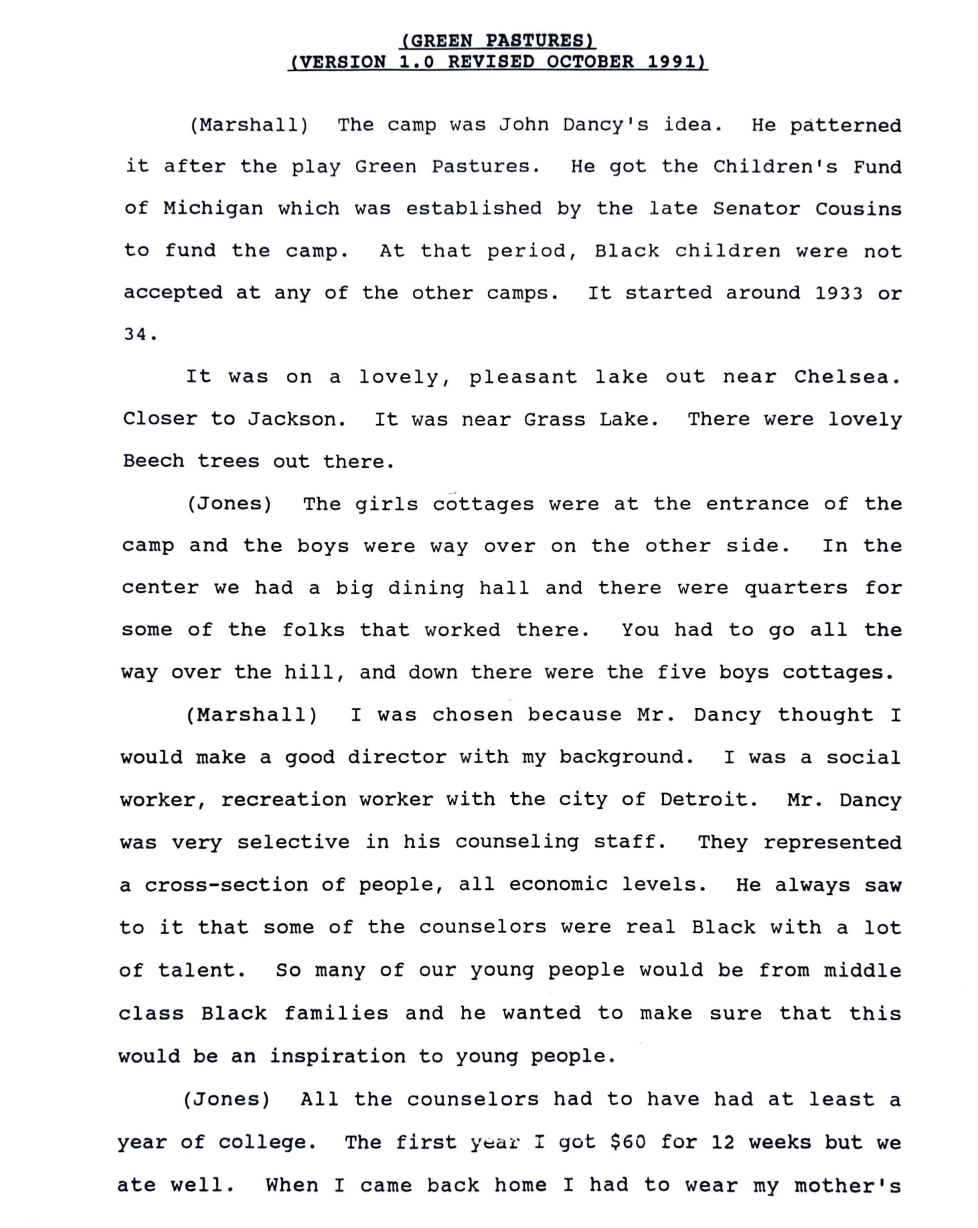

One of the League’s most popular programs was the Green Pastures Camp, a summer camp specifically for Black children. Founded by Urban League director John C. Dancy, the camp was created because other camps would not admit Black children. Attendees remembered the camp as a fun place where they could be around other kids just like them. Eleanor Boykins Jones remembered, “It was on par with any campsite you would see anywhere, with a health cottage and the five cottages nicely spaced.”

As the Black population of Detroit increased to 120,066 in 1930, 149,119 in 1940, and 300,506 in 1950, the Urban League continued to play this role and received increasing assistance from Black churches, especially the Second Baptist Church and the Bethel AME Church.

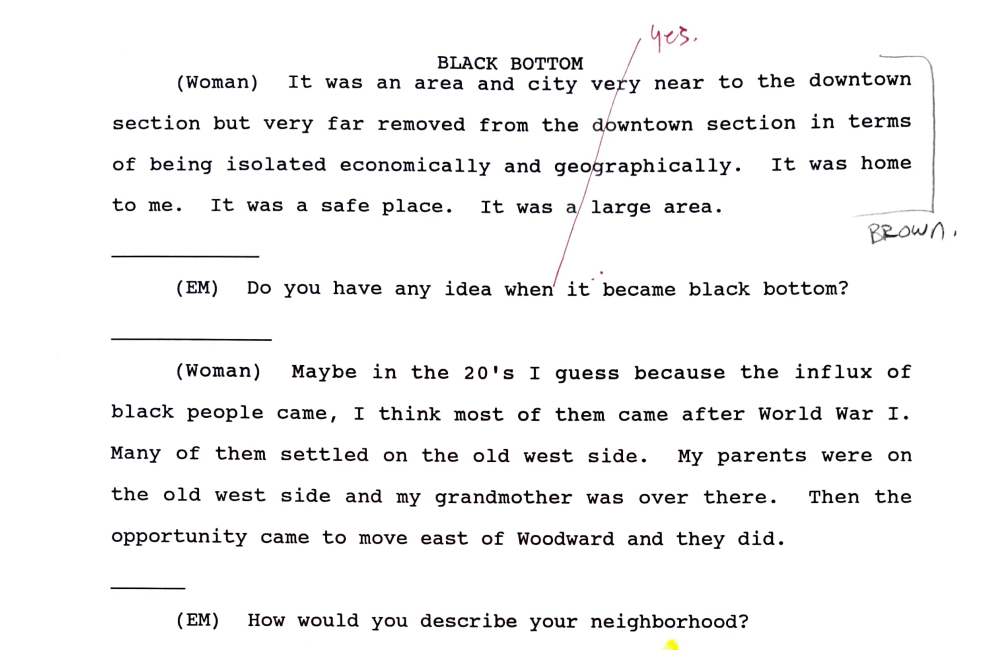

Due to racial discrimination in housing, Black migrants were concentrated almost entirely in a neighborhood just east of downtown called Black Bottom, but also lived in a few Black enclaves throughout the city. In Black bottom, Black people lived in some of the oldest housing in the city, largely owned by absentee landlords. Seeing the limited housing available to Black migrants as an opportunity to make money, landlords broke houses up into multiple units, leaving many of them without electricity and/or plumbing. As a result, Black Bottom became one of the most densely populated neighborhoods in the city and one of its poorest.

About 25% of Black Detroiters lived outside Black Bottom. In the 1920s, middle class Blacks began leaving Black Bottom and purchased homes on the West Side near Tireman and Grand Boulevard. Also in the 1920s, at the encouragement of the Urban League, several Black migrants settled on former farmland near Eight Mile and Wyoming where they hoped to build their own homes and live the American dream. Detroit’s most affluent Blacks residents lived in Conant Gardens on Detroit’s Northeast Side. The neighborhood was made up of the city’s Black elite including ministers, lawyers, teachers, and business people fleeing poorer Blacks on the west and east sides.

Despite the demand for labor that drove the great migration, due to racial discrimination Black migrants to Detroit did not always have the easiest time finding jobs. By 1915, the automobile industry was the largest industry in Detroit and it employed almost no Black workers. In 1920, only five of the 67 auto plants in the city hired Black workers, the majority of which worked at Packard. However, by 1920, Ford Motor Company had become the largest employer of Blacks, employing 1,675 back workers, promising them all $5 a day. In contrast to other companies that concentrated Black workers in the worst and most dangerous jobs, at Ford Black workers were hired in all positions in the factory, including skilled positions. Because Ford provided the possibility of promotion for Black workers, Henry Ford became a hero to the Black community and was able to use Black workers as a weapon against unions.

Ford hired his Black workers on recommendations from pastors who opposed Black worker’s participation in labor unions. Accordingly, Black pastors with a line into Ford saw their congregations grow as would be Ford workers and church members hoped for referrals to Ford. These Black churches came to depend on Ford for a growing membership and became increasingly active in publicly opposing Black workers in unions. To protect their relationship with Ford and keep their members employed, some Black preachers refused to let Howard University president Dr. Mordecai Johnson speak to their churches because he urged Black workers to join unions.

This pattern in employment persisted until President Franklin Roosevelt passed Executive Order 8044 in 1938 making discrimination in defense related industries illegal. In housing these patterns persisted until the 1950s when Black Bottom was leveled to make way for Interstate 375.

Sources:

Beth Bates, The Making of Black Detroit in the Age Henry Ford, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2012

Elaine Latzman Moon, Unsung Heroes, Untold Tales: An Oral History of Detroit’s African American Community, 1918-1967, Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1994

Richard Walter Thomas, Life for Us is What We Make it: Building Black Community in Detroit, 1915-1945, Bloomington, University of Indiana Press, 1992

In this 1990 oral history, UAW Local 600 founder Dave Moore describes his family’s move to Detroit from South Carolina during the Great Migration in the 1920s. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Photograph of Detroit Urban League Director John C. Dancy, taken in 1958. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Oral history interview with former attendees of the Detroit Urban League’s Green Pastures camp, conducted by Elaine Latzman Moon in 1991. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

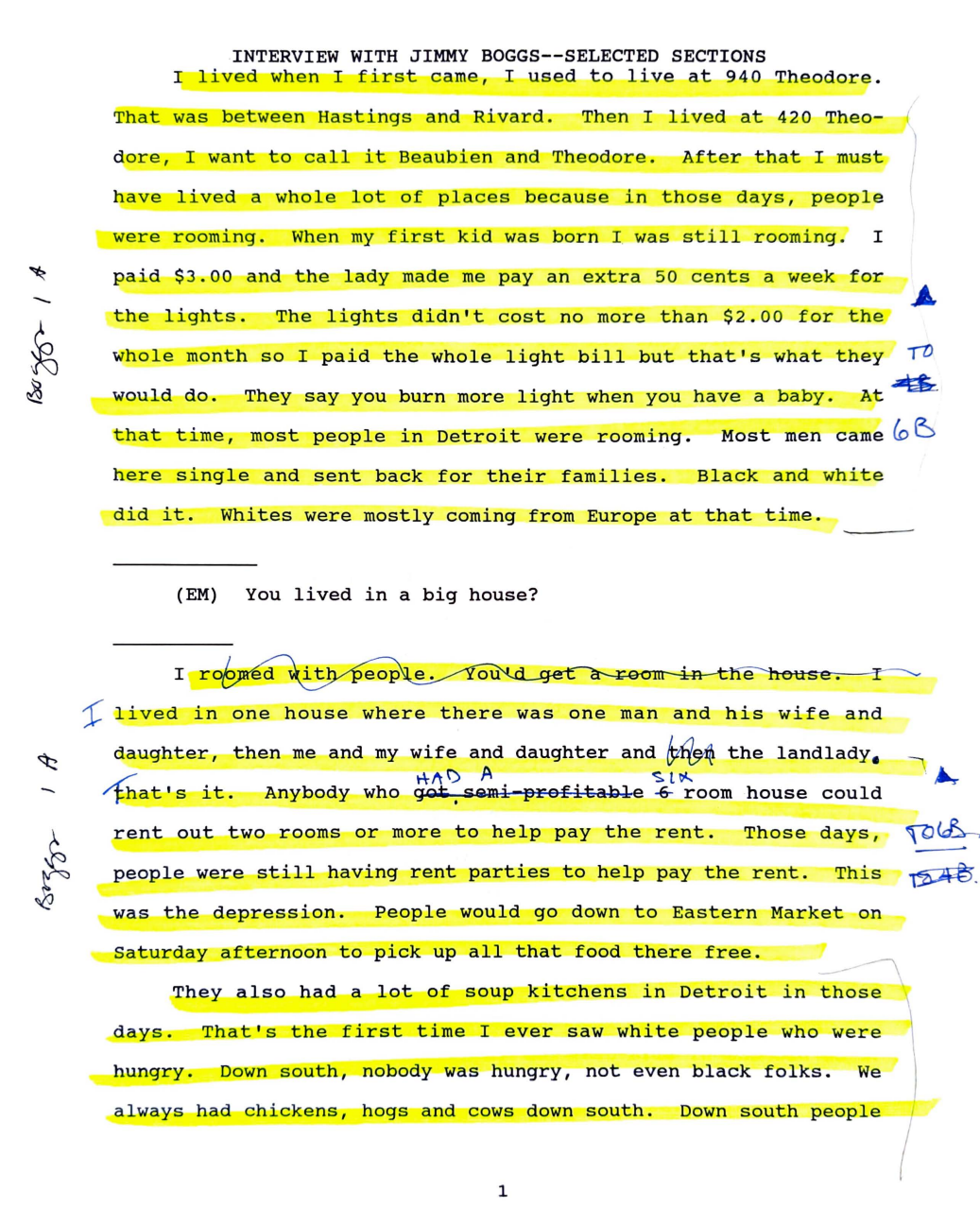

Oral history interview with labor and civil rights activist James Boggs, conducted by Elaine Latzman Moon in 1991. Boggs discusses the Great Migration, labor organizing, and civil rights in Detroit.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

In this oral history interview from 1992, Gwendolyn Edwards describes working conditions and union organizing at the Ford River Rouge Plant in the 1930s. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

A booklet titled “Negro Workers in Free America” by Rev. Francis J. Gilligan, which describes racial discrimination in employment experienced by Black workers. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Explore The Archives

In this 1990 oral history interview, Joe Barrow Louis, Jr., son of legendary boxer Joe Louis, describes how an encounter with the KKK in Alabama prompted his grandparents to move to Detroit. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Oral history interview with former residents of Detroit’s Black Bottom neighborhood, conducted by Elaine Latzman Moon between 1990-1994. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

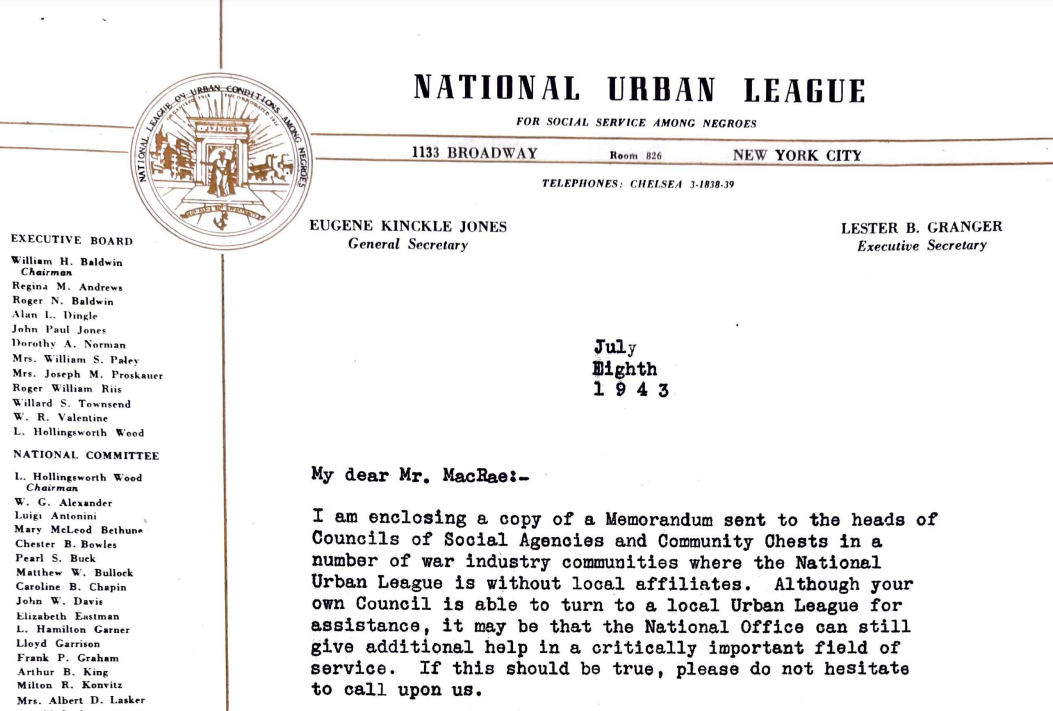

A letter from National Urban League Executive Secretary Lester Granger to Detroit historian Robert McRae on July 8, 1943. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clips from 2018 interviews with Helen Moore and Elliott Hall, in which they discuss growing up in Detroit’s Black communities in the 1950s. — Videography: 248 Pencils

This map shows Black Bottom as it stood in 1951. Visit Black Bottom Archives for an interactive map and digital archive of Black Bottom. Credit: Black Bottom Street View/Black Bottom Archives

Oral history interview with labor and civil rights activist James Boggs, conducted by Elaine Latzman Moon in 1991. Boggs discusses the Great Migration, labor organizing, and civil rights in Detroit.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University