Housing Segregation

Before World War II, the housing situation for Black Detroiters could be characterized by an increasing demand for housing and an increasing resistance towards integrated neighborhoods amongst whites. Consequently, the masses of Black residents were forced to live almost exclusively in a small, overcrowded, working-class neighborhood called Black Bottom on the Lower East Side. This segregation was maintained, in part, by a real estate practice called restrictive covenants.

Although federal law made it illegal to separate sections of cities by race after 1917, because whites resisted the idea of Black neighbors, real estate agents and developers developed restrictive covenants as a way to continue selling houses. As the citywide demand for housing increased due to the migration of Blacks and whites from the south, developers wrote racially restrictive clauses in property deeds regarding who could own homes. Working in tandem with developers, real estate agents then used the existence of these covenants as a selling point for homes. One ad described a development as made up of “the kind of people you would be glad to have next door.”

The demand for racially restricted housing among whites was partially driven by the movement of Black Detroiters beyond Black Bottom, a practice that often exploited Black residents and accelerated the creation of racially restricted neighborhoods. For example, although it was false, because whites largely believed that Black neighbors lowered property values, real estate agents would tell white homeowners that a Black “invasion” was coming and whites would rapidly sell their homes to agents below market value. Real estate agents would then sell these homes to Black Detroiters at a higher than market price. Whites would then move into racially restrictive developments to avoid losing money on their homes in the future.

Other whites prevented Black Detroiters from moving into their neighborhoods through violence. In 1925, violence flared in Detroit when a Black doctor named Alexander Turner who was head of surgery at Dunbar Memorial Hospital tried to move into Tireman that June. White residents greeted him by throwing rocks and smashing windows. In July, Vollington Bristol also tried to move into Tireman. From July 7th-9th he fought white mobs of over 2,000 people gathered in front of his house with shotguns, revolvers, and rifles. Bristol was able to fight for three nights because Black Detroiters, also armed, gathered to fight the whites. After exchanging gunfire on the 9th, nineteen whites and twenty-four Blacks were arrested. The following day the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross of Bristol’s lawn.

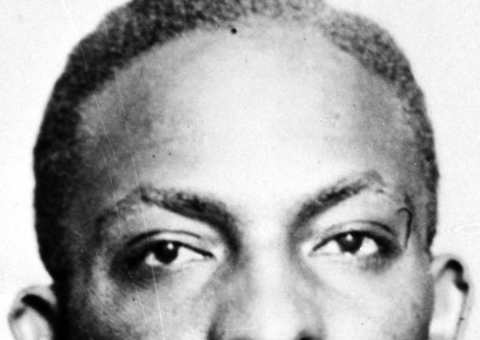

This violence made national news when, in September, Dr. Ossian Sweet moved his family into the Garland neighborhood. During the Sweet’s second night, a white mob threw rocks through the Sweet’s windows. As the mob grew more hostile, gunshots were fired from inside the house, resulting in the death of one white man and the injury of another. Sweet, his wife, and nine other Black Detroiters were charged with murder. With legal support from the national NAACP, charges were dropped against three defendants before trial and the trial of the remaining eleven resulted in a mistrial.

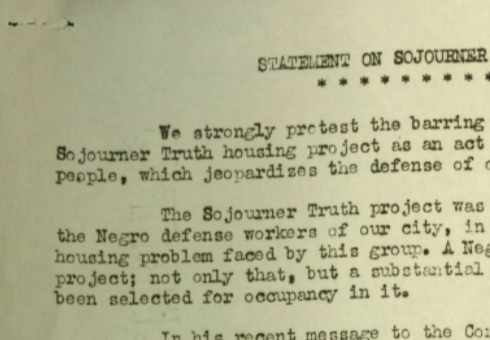

At the height of World War II, the resistance of whites to integrated neighborhoods combined with a severe housing shortage resulted in similar violence at the opening of a housing project named the Sojourner Truth Homes. Designed as a public housing complex for Blacks, the two hundred-unit complex was built in the Seven Mile-Felon neighborhood because it was close to Conant Gardens, a middle class Black neighborhood. However, when plans were announced, Black and white residents opposed the project’s construction. Despite this initial unity, middle class Black residents of Conant Gardens quickly dropped their opposition to the project when the racism of their white counterparts became clear.

In response to white pressure, protest, letter writing, and lobbying city council members, the Federal Housing Authority switched the racial designation of the project three times. Meanwhile, union activists and public housing advocates organized to maintain Black people’s access to the project. With only one other project in the city allowing Black residents, Sojourner Truth became a major site of conflict.

When the first Black families moved in February 1942, both white opposition and supporters of Black Detroiters gathered at the site and by the end of the day more than 1,000 people were in the streets. Fighting erupted, forty people were injured, 220 arrested, and 109—all Black—were held for trial. In the wake of what has come to be called the Sojourner Truth riot, the Detroit Housing Commission created a policy to guarantee that the construction of new public housing would “not change the racial pattern of the neighborhood” in which it was to be built.

According to historian Thomas Sugrue, white racists considered this policy a victory and learned a valuable lesson from the struggle. “After the Sojourner Truth incident and the Detroit Riot of 1943, white community groups learned to use the threat of imminent violence as a political tool to gain leverage in housing debates. City officials, desperately hoping to avoid racial bloodshed, had no choice but to take seriously the specter of civil disorder.”

References:

Beth Bates, The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2012

Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2005

Richard Walter Thomas, Life for Us is What We Make it: Building Black Community in Detroit, 1915-1945, Bloomington, University of Indiana Press, 1992

Detroit’s east side showing Brush, Beaubien, St. Antoine and Hastings streets looking south on Sept. 12, 1933. The diagonal street is Gratiot. –Credit: Detroit News Archive

A pamphlet produced by the American Council on Race Relations in 1945, titled “Hemmed In: The ABCs of Restrictive Covenants.”–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 2018 interview with Charles Ezra Ferrell, in which he discusses the trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet in 1925. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Hundreds of Black Detroiters attend a mass meeting in Cadillac Square in support of housing for war workers on April 12, 1942. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Explore The Archives

A 1958 photo of Dr. Ossian Sweet’s home, a two-story brick house at 2905 Garland Road on the East Side of Detroit. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

An undated photo portrait of Dr. Ossian Sweet. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

The defense team for Henry Sweet, brother of Dr. Ossian Sweet in 1926. From left to right: Henry Sweet, Julian Perry, Thomas Chawke, Clarence Darrow. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

An undated photo portrait of Mrs. Gladys Sweet, wife of Dr. Ossian Sweet. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

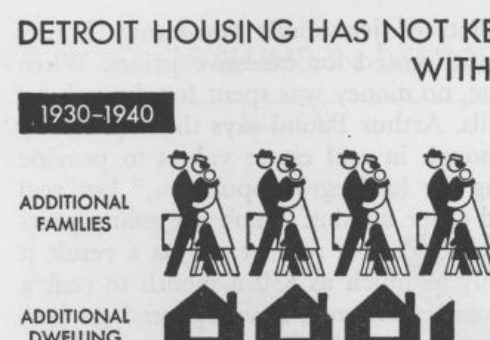

During and after World War II, an influx of migrants looking for autowork made Detroit a very cramped place to live. African Americans bore the brunt of these conditions since most of the housing in the city was not available to Black buyers and renters. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

An undated speech (presumbly spoken sometime in 1945) by Gloster Current, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, in which he discusses both the lack of housing options for Black Detroiters and housing segregation.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

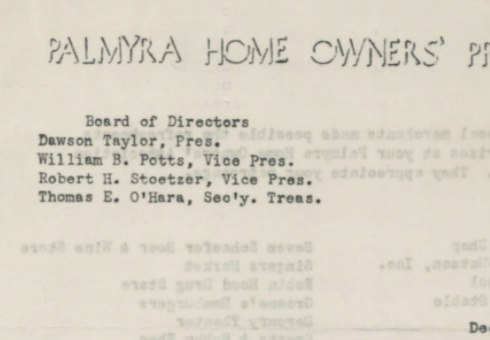

A letter from the Palmyra Home Owners’ Protective Association to its members, dated December, 3, 1948. The Palmyra Home Owners’ Protective Assocination was one of my similar organizations in Detroit that fought against racial integregation in all white neighborhoods in Detroit.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

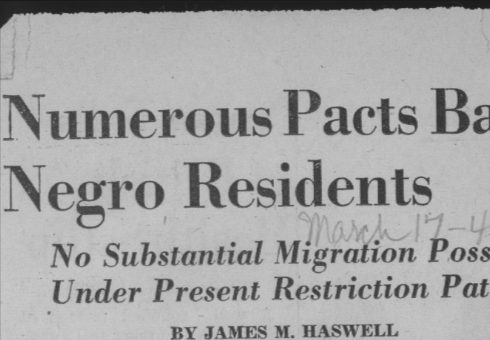

A 1945 article from the Detriot Free Press by James M. Haswell titled “Numerous Pacts Bar Negro Residents: No Substantial Migration Possible Under Present Restriction Patterns.” The article discusses restrictive covenants in Detrit, which are binding contracts forcing owners to “not permit Negro occupancy.” It goes on to examine the parts of the city that have the most restrictive covenants compared to neighborhoods with the least.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

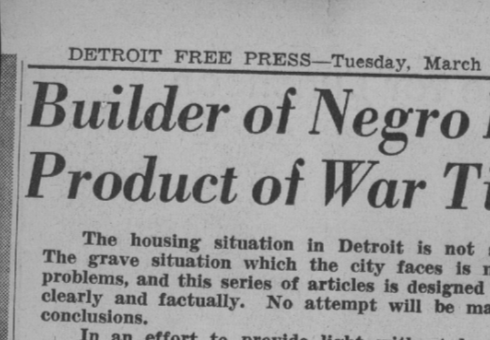

A 1945 article from the Detroit Free Press by James M. Haswell titled “Builder of Negro Homes Product of War Times,” which discusses the house shortage during World War II. As a result, speculative slumlords came to prey on Black tenants who were discriminated against at most apartments and houses in Detroit. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Numerous leaders of organizations around Detroit signed this statement in 1942 to protest “the baring of Negro defense workers from the Sojourner Truth housing project,” January 28, 1942. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

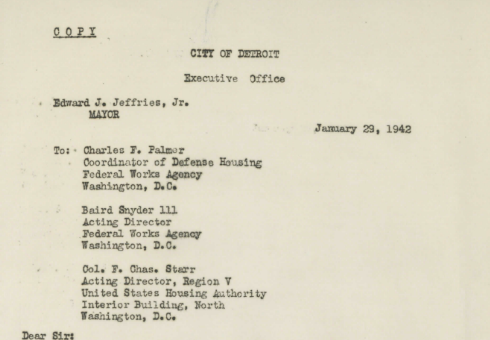

This letter from Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries, dated January 29, 1942, is addressed to directors of several departments of the United State federal government in charge of housing. In the letter, Mayor Jeffries argues that the descision to turn the Sojourner Truth Homes into an all-white project is a mistake and that little to no other areas in the city are suitable for a project of comparble size for Black defense workers.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

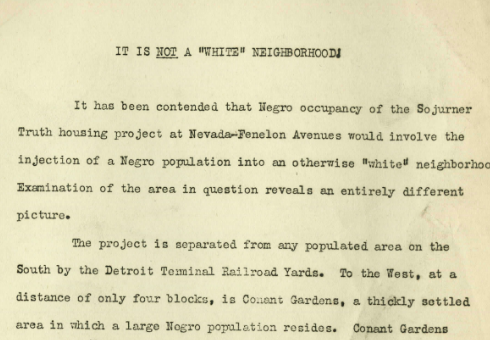

An undated leaflet about the Sojourner Truth Homes project, likely from 1943. The area around the Sojourner Truth homes was diverse and mixed. White racists who opposed the homes falsely claimed the project represented a forced encroachment on a “white neighborhood,” but as the statement says, this was false.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

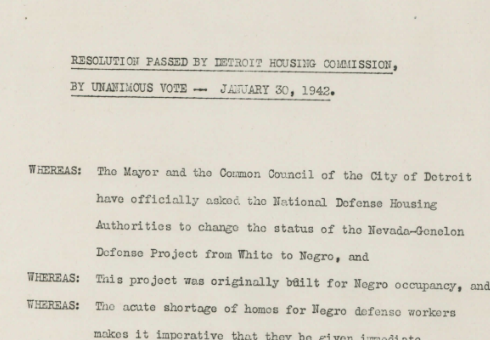

On January 30, 1942, the Detroit Housing Commission passed a resolution by unanimous vote to make a request to the National Defense Housing Authorities to reverse a descision that turned the Sojourner Truth Housing projects into an only white project.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

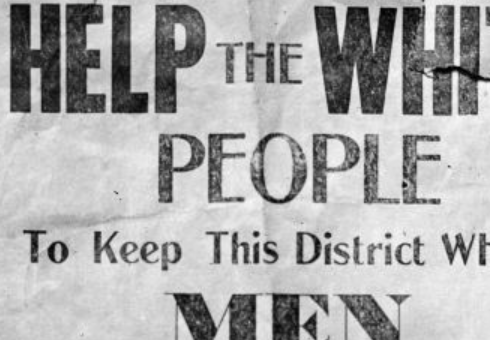

This flyer calling for men to be sent to “Nevada and Fenlon” to “Keep this district white,” was a piece of the organizing material that attracted huge crowds of hostile whites to attack Blacks moving into recently constructed housing.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

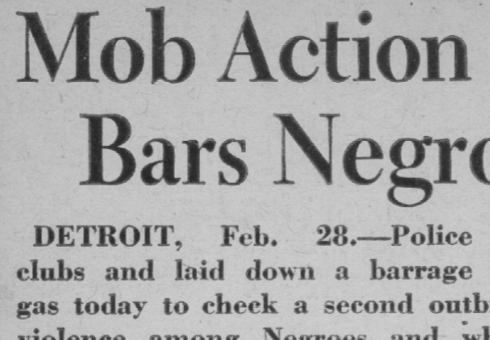

This Februrary 28, 1942 article from the Detroit Free Press discusses the “rock-throwing mob of whites” who “halted occupancy of the $1,000,00 Sojourner Truth war-housing project.” As the housing shortage rocked Detroit in the midst of World War II, tensions over housing segregation grew more violent everyday.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

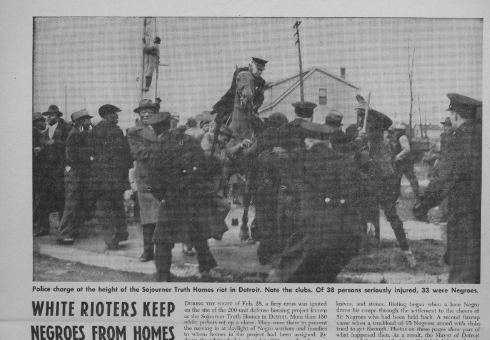

This undated article, most likely from a special edition of the Detroit Free Press or The Detroit News , starts off mentioning the “fiery cross” that was ignited on the site of the housing project. The pictures only do partial justice to reflect the racial tensions that spiraled into violence and chaos on the night of February 28, 1942.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The almost completely white Detroit Police Department attempted to keep the peace between white protestors and Black new homeowners, however, often times they beat and arrested far more peaceful Black movers than hostile whites.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Police officers at the Sojourner Truth Housing Project attempt to arrest a Black child as a woman attempts to protect him in 1942.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

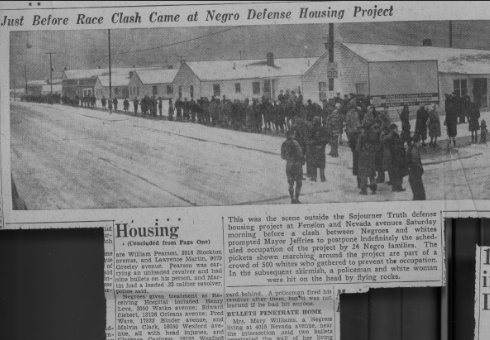

This March 1, 1942 article from The Detroit News, titled “Just Before Race Clash Came at Negro Defense Housing Project,” details the violence of thousands of whites who attacked a few Black families and police officers.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

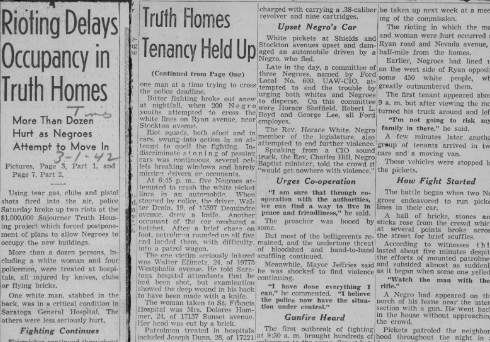

A March 1, 1942 article from the Detroit Times, titled “Rioting Delays Occupancy in Truth Homes: More Than a Dozen Hurt as Negroes Attempt to Move In.” The chaos and violence at the Sojourner Truth housing project almost involved federal troops on March 1, 1942. The miniature “race riot” forshadowed the larger, more violent race riot of 1943.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Black men, most likely new homeowners, with their hands up as police question them.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

A bloodied Black man being arrested by police as a group of Black men watch from the porch. It is unknown who caused the man’s injuries, but presumbly it occurred during the white mob attack at the Sojourner Truth projects.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

This photo shows Black Detroiters meeting around the porch of a house in the Sojourner Truth projects, presumbly to discuss the hostile police and whites.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

The front page of the PM Late War News from Tuesday, March 3, 1942, which includes a bombastic image of a mounted police officer charging into a crowwd of whites, police officers, and African Americans, portrays the chaotic and violent white response to breaching housing segregation..–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

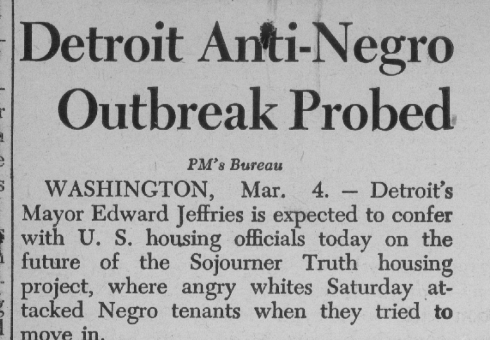

Newsclipping from March 4, 1942 titled “Detroit Anti-Negro Outbreak Probed.” After the riot at the Sojourner Truth housing project on Februrary 28, Detroit’s Mayor Edward Jeffries, met with U.S. housing officials to discuss the future of the project. After the Ku Klux Klan organized riot, white racial liberals like Mayor Jeffries constrained despite major support from the Black community of the city.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

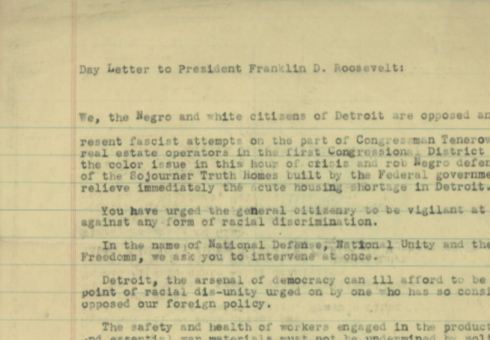

An undated draft letter from Black Detroit leaders to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1942. The Sojourner Truth project crisis compelled the attention of almost every major leader in Detroit. Among the notable indivudals listed on this letter to President. Franklin D. Roosevelt are Coleman Young, Snow F. Grigsby, Louis Martin, John Williams, and Charles C. Diggs. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

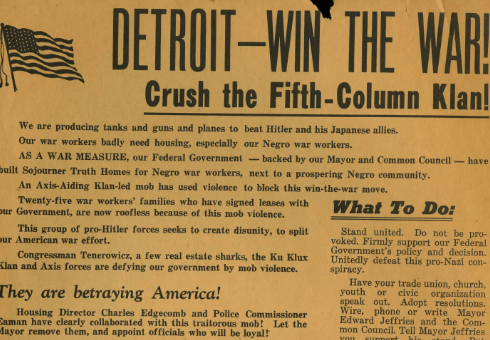

This flyer created by the Sojourner Truth Citizens’ Committee, which was lead by Rev. Charles A. Hill, provides a summary of the Sojourner Truth housing crisis and what one can do to support the project. The flyer appeals to American’s sense of patorism in the midst of World War II by arguing that those against the project as “betraying America.”–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

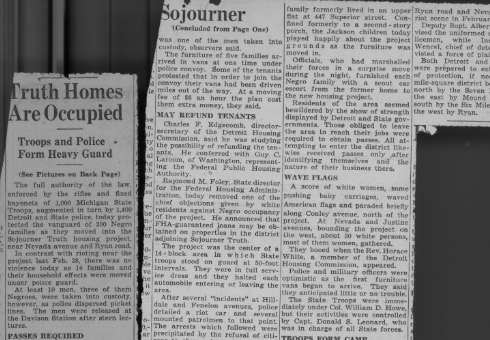

After 1,000 Michigan State Troopers and 1,400 Detroit and State police occupied the area around the Sojourner Truth homes, 200 Black families were finally able to be moved in. Despite the lack of violence, white hostility still lingered as hundreds of white protestors surronded the project while they shouted racial epiphets and threatened more violence.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Michigan State Troopers guarding Sojourner Truth Housing Project, where whites in the surrounding neighborhood were opposed to Black families moving in. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

A Black family moves into their new home in the Sojourner Truth projects in 1942.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

An April 13, 1942 article from the Detroit Free Press titled, “3,000 Ask Project at Negro Rally: Immediate Occupancy is Demanded After Parade Honoring Sojourner Truth.” This article corresponds with the photo above of the mass rally in Cadillac Square. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

A page from the PM’s Daily Picture Magazine titled “14 Negro Families Move Sojourner Truth Houses.” On April 30, 1942, fourteen Black families were escorted by 2,000 guards to move into the Sojourner Truth federal housing project in Detroit. They were met with “1,200 whites” who “attacked three Negro families,” marking one of the most violent and incidenary instances of white hostitlity to perceived Black encroachment.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

An April 30, 1942 article from the Detroit Free Press, titled “1,750 Guards Keep the Peace as Negroes Enter Truth Project.” Onlookers watching the Black families move into the Sojourner Truth housing project remarked that it was the oddest site. Moving vans “were whisked into the guarded project in a convoy of police motorcycles and squad cars.” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

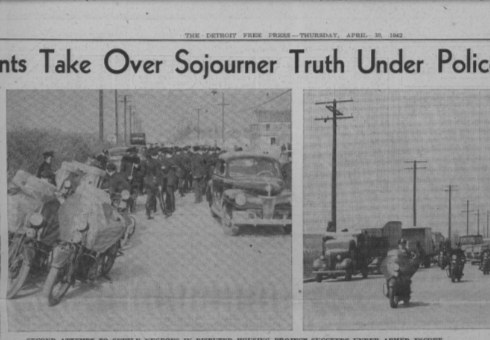

An April 30, 1942 article from the Detroit Free Press, titled “Tenants Take Over Sojourner Truth Under Police and Troops.” The article highlights a series of important snapshots of the second attempt to move in Black families into Sojourner Truth. This time, they had much more police and planning including Michigan State Troopers.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A March 16, 1945 article from the Detroit Free Press by James M. Haswell, titled “City’s New Housing Fails to Meet Need.” Even after the Sojourner Truth incidents, an acute housing shortage still was present in Detroit. According to Haswell, the “Negro situation is most acute” because there are 4.5 Negroes for “each Negro dwelling unit.”–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clip from a 2018 interview with Helen Moore, in which she shares her memories of white flight from Detroit in the 1940s-50s and its impacts on the city. –Videography: 248 Pencils

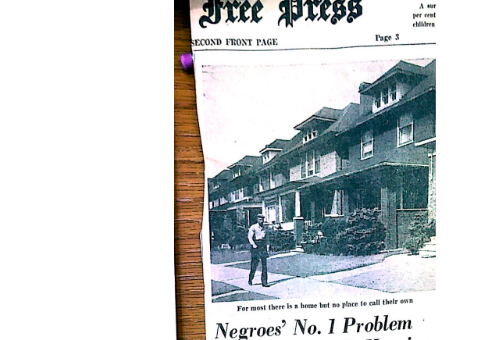

Undated (presumbly from mid-late 1950s) newsclipping from the Detroit Free Press, titled “Negroes’ No. 1 Problem In Detroit Is Still Housing.” By the late 1950s, racism and segregation pervaded Detroit’s housing market, drivng housing shortages and slum-like conditions of living for most African American residents..–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

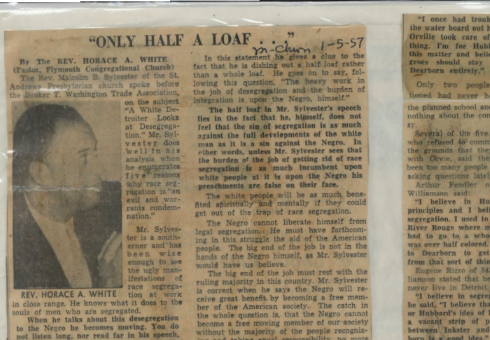

A January 5, 1957 article in the Michigan Chronicle by Rev. Horace A. White, titled “Only Half a Loaf” by Rev. Horace A. White. Whereas segregation in the form of Jim Crow existed in the South, Rev. White explicates the regime of segregation in the North. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A June 3, 1957 article in the Detroit Free Press by Evelyn S. Stewart, titled “Big Problem To Negroes Still Housing: Moves into White Blocks Often Bring Headaches.” For most African Americans in Detroit during the 1950s-60s, housing remained one of the major issues. Although segregation was illegal in the law, de facto segregation was common, as Detroiters were segregated into Black Bottom, Paradise Valley, and a few enclaves in and around the city.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Civic associations and homeowners associations grew in the 1940s and 1950s as white homeowners organized to prevent Black residents from moving into their neighborhoods, sometimes violently. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A 1943 map illustrating the racial geography and segregation surrounding the Sojourner Truth Homes. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.