Police and the Black Community

Ron Scott’s family moved from Chicago to Detroit in 1953 when he was six years old. Walking down the street with an uncle visiting from Louisiana seven years later, a four-man unit of police officers known as “the Big Four” got out of their car and approached him. With a shotgun in the thirteen years-old Scott’s face, one of the officers told him, “Nigger, if you breath we’ll blow your head off.” Scott’s experience as a young man was typical of young black men’s experience with the Detroit Police Department.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, black Detroiters experienced the Detroit Police Department as a terrorist organization. Although no part of the department was immune from poor treatment of blacks, the most consistent abuse came at the hands of the Big Four, a group of three plan clothes officers and a uniformed driver that patrolled black neighborhoods with shotguns. This general environment of terrorism and hostility, as represented by Ron Scott’s teenage experience, led many black Detroiters to see the police as an occupation army in the city’s black neighborhoods. Consequently, police brutality and terrorism became one of the primary forces shaping the experience of black Detroiters and a primary motivation for black people’s resistance.

Growing up as a child in Detroit, Ike McKinnon saw the Big Four harass black men in his West Side neighborhood frequently and believed only people who had done something wrong faced their wrath. Then at fourteen years old, while leaving school and walking home the Big Four pulled up on him. Because he was a good student and well behaved, he assumed the interaction would go fine. When they began to call him racist names and beat him without warning, he protested and was beat worse. “As this was going on, time stands still. I remember looking as they were beating me up and I could see all the people standing, looking. And they’re looking but they couldn’t do anything because it was my turn to get my ass kicked, you know whipped.”

After the police finished beating him, he went home and chose not to tell his parents. McKinnon chose not to tell his parents because, “If I had I had told my parents about it when I got home, they would have gone to the police station and Lord knows what might have happened to them. They probably would have done much worse to my mother and father. That’s how bad it was, and there’s no denying the fact that it happened.”

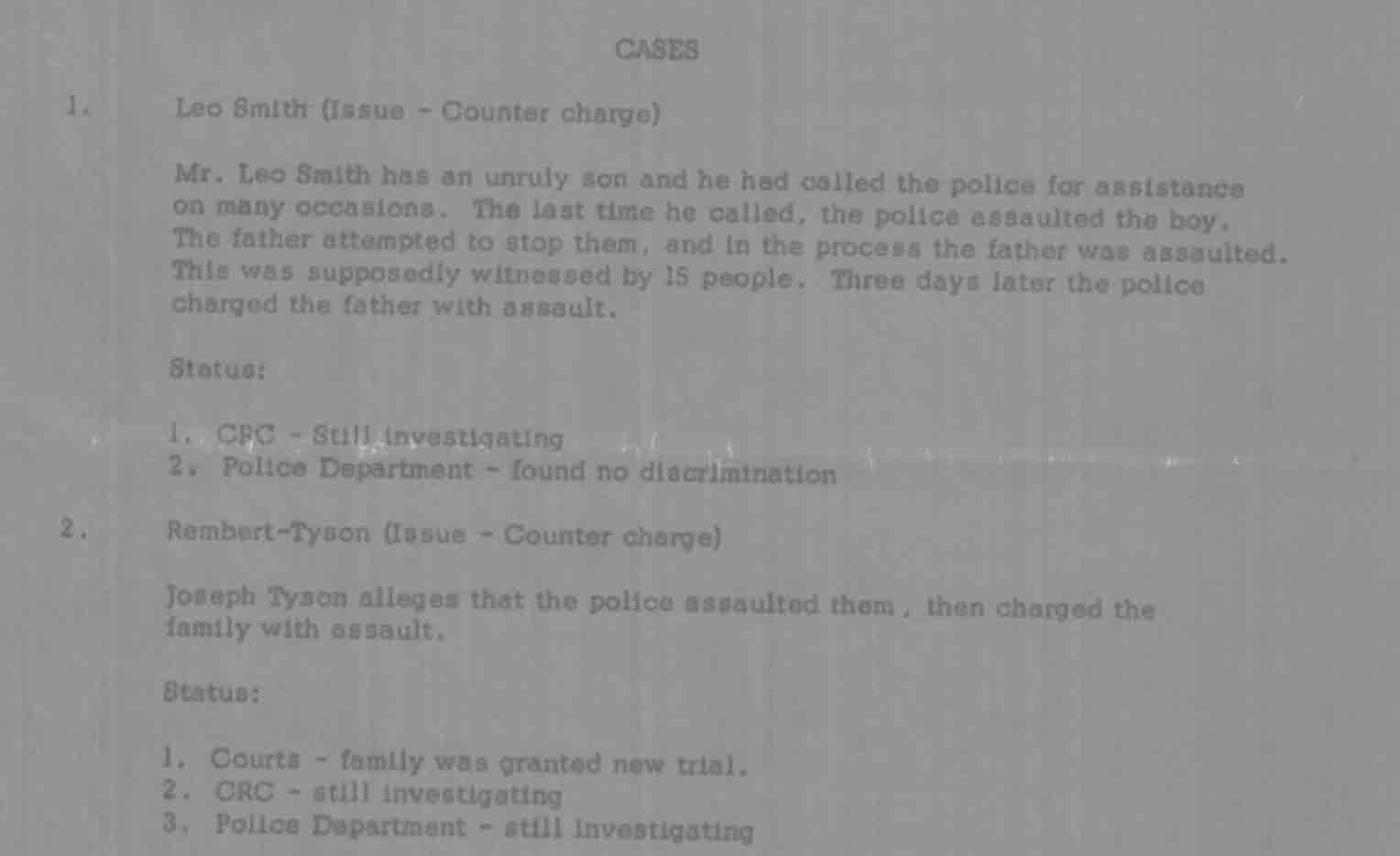

Even if McKinnon’s parents had filed a complaint and were brutalized by police, according to now retired white police officer Henry Duzinski, their complaint would have meant nothing. Complaints “didn’t get anywhere, because there was a cover up. The blue curtain would descend and not only I was aware of it, but commanders were aware of it. There’d be a cover up right in front of the sergeant…right up the ladder of command…. It was common knowledge that if you [police officers] were involved in a serious incident that you need not worry because the prosecutor and the medical examiner was on your side.” This kind of protection gave Detroit police officers carte blanche to regularly terrorize black Detroiters in the basement of the Hunt Street Station where, according to Ron Scott, “cops would take folks down in the basement and beat them silly.”

Growing up in a city where the police were so brutal children were scared to tell parents because they were afraid of what might happen to their parents, by the early 1960s black Detroiters developed great anger towards the police. Because complaints meant nothing, this anger began fueling protest in 1963.

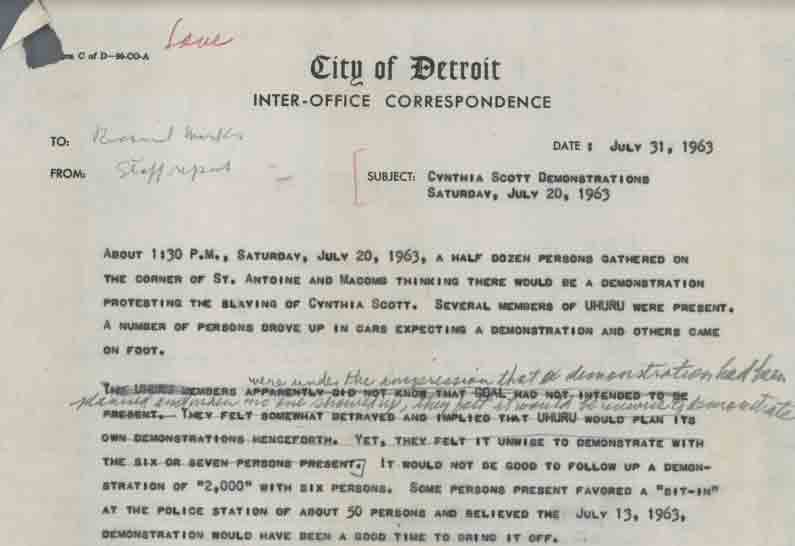

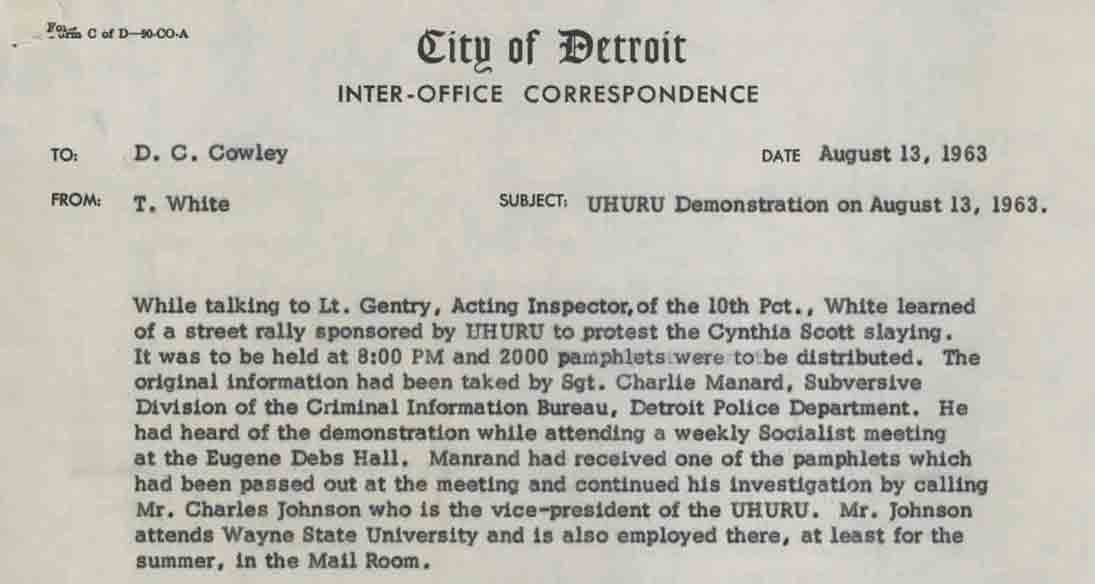

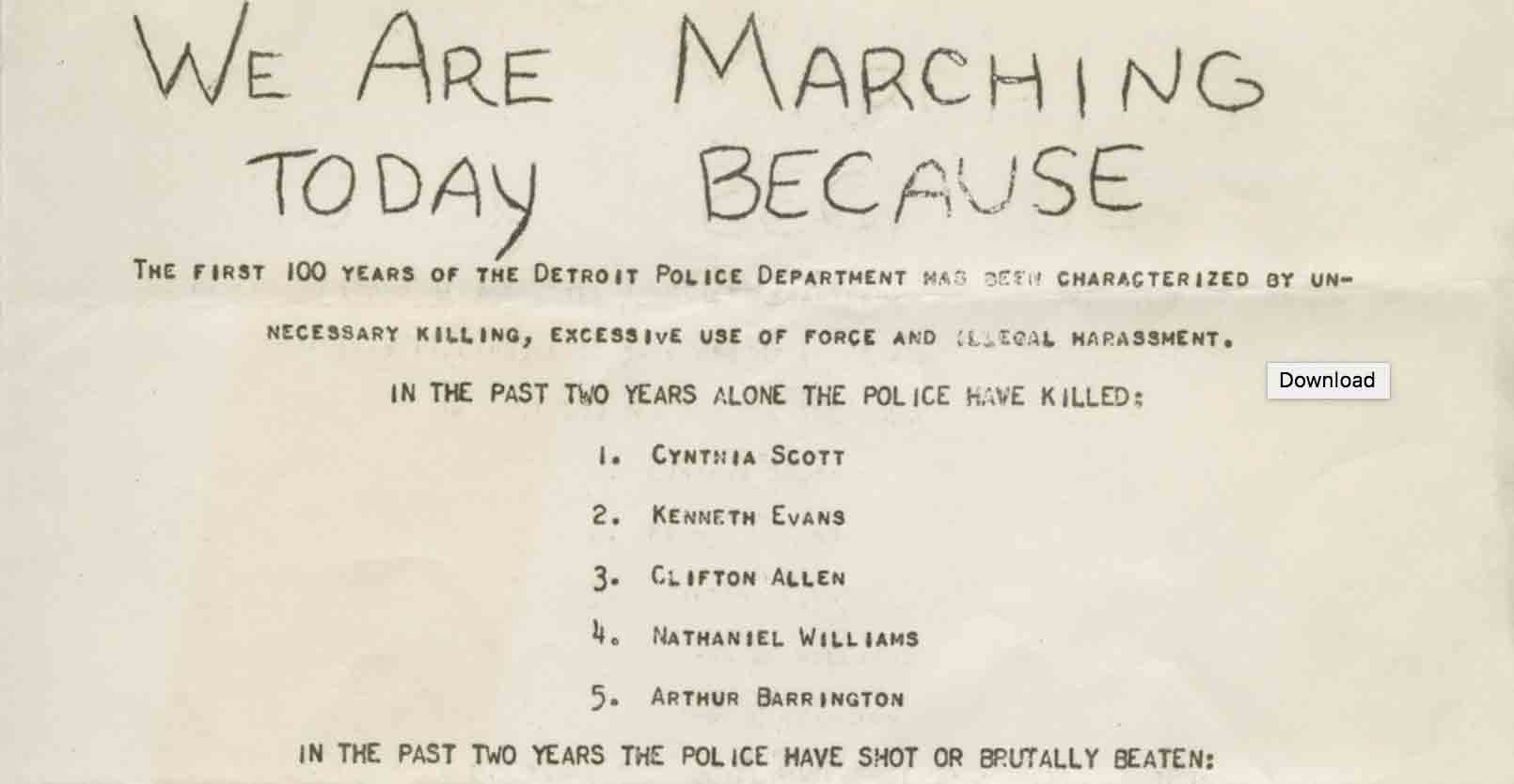

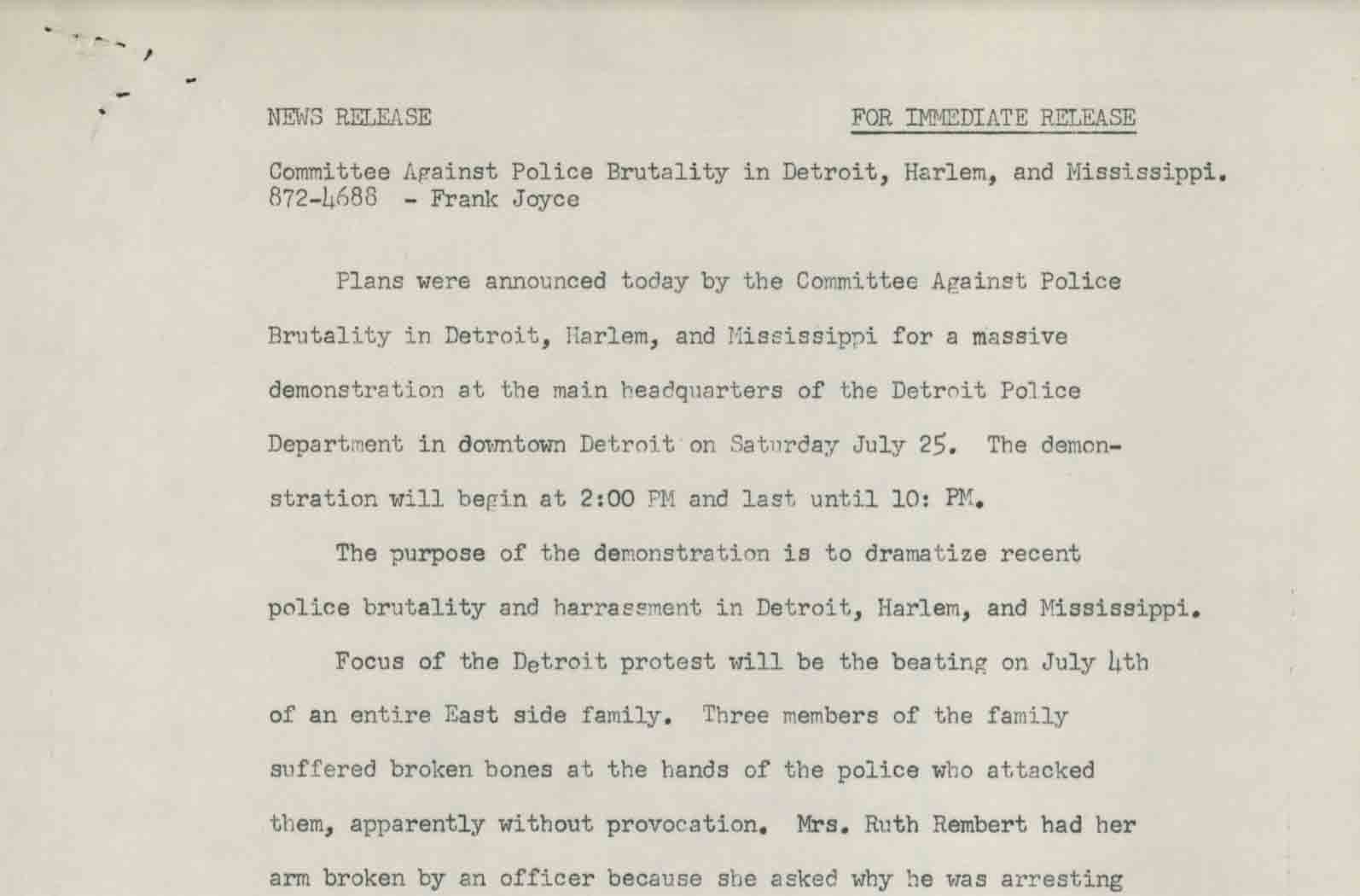

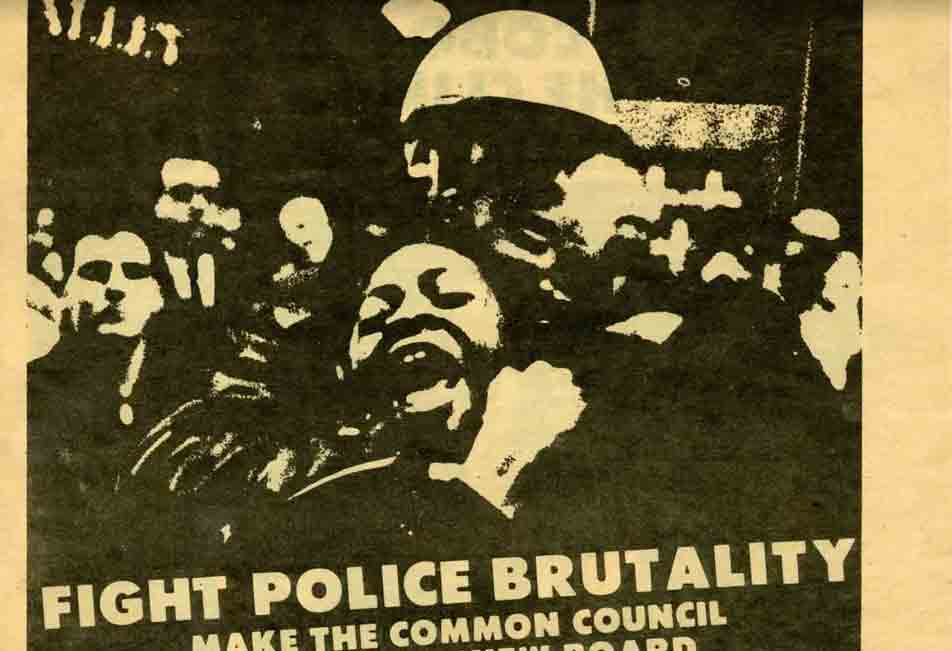

After a white police officer with a reputation for brutality killed a black sex worker named Cynthia Scott and faced no punishment in 1963, GOAL and Uhuru organized a protest at police headquarters. With as many as 2000 people at the demonstration chanting “Stop Killer Cops,” the anger at the police was so great that people wanted to storm the police station. Grace Lee Boggs, one of the demonstration’s organizers, remembered one woman specifically who “really wanted to attack police headquarters. She said she knew some people were gonna die, but it would have been worth it. That gives you some sense of the hostility and the anger which was mounting.”

Following this demonstration, Uhuru organized additional actions to demand that the acquitted officer be removed from the police force. Uhuru organized a fifteen-person sit-in of Mayor Cavanaugh’s office and GOAL attorney Milton Henry filed a $5 million lawsuit filed by on behalf of Cynthia Scott’s mother. The city responded by relieving the officer of car patrols and by revising the process the department used to deal with the use of fatal force by officers. Despite the victories of black activists, police brutality remained a constant aspect of black life in the city.

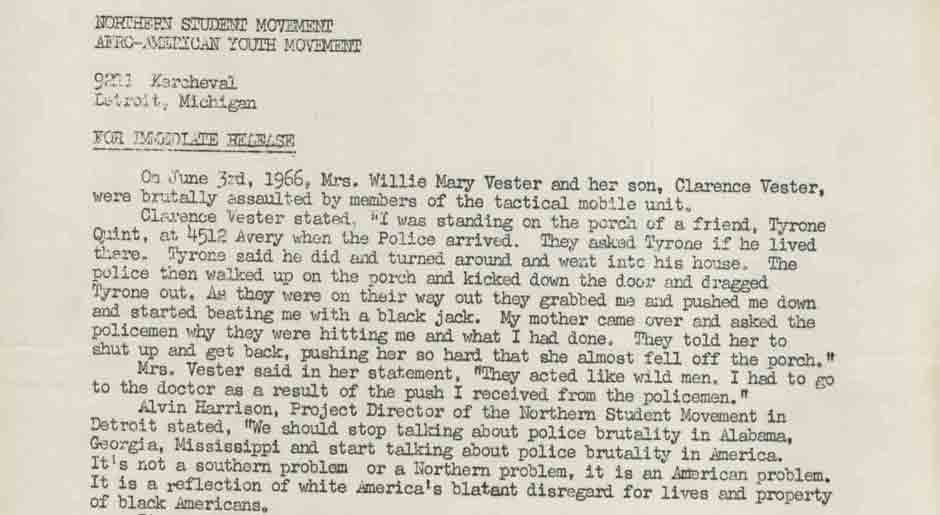

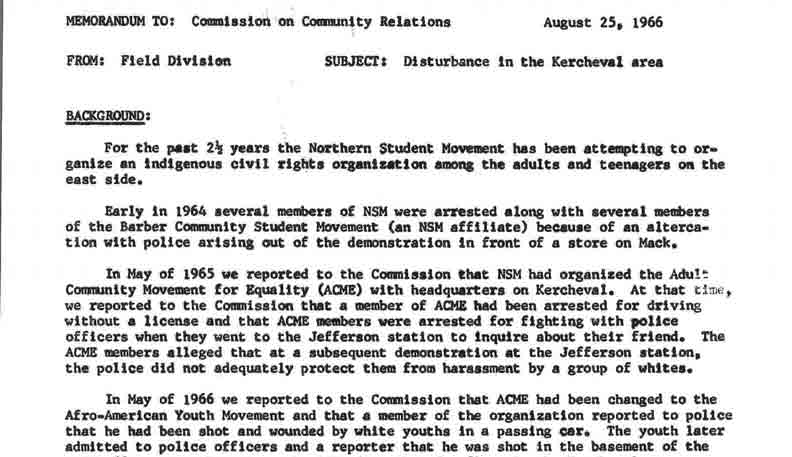

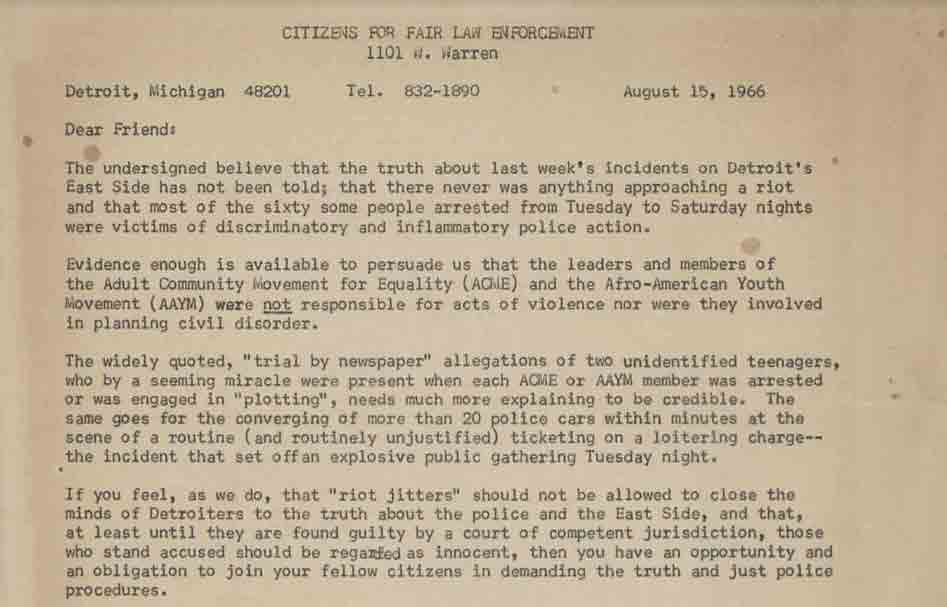

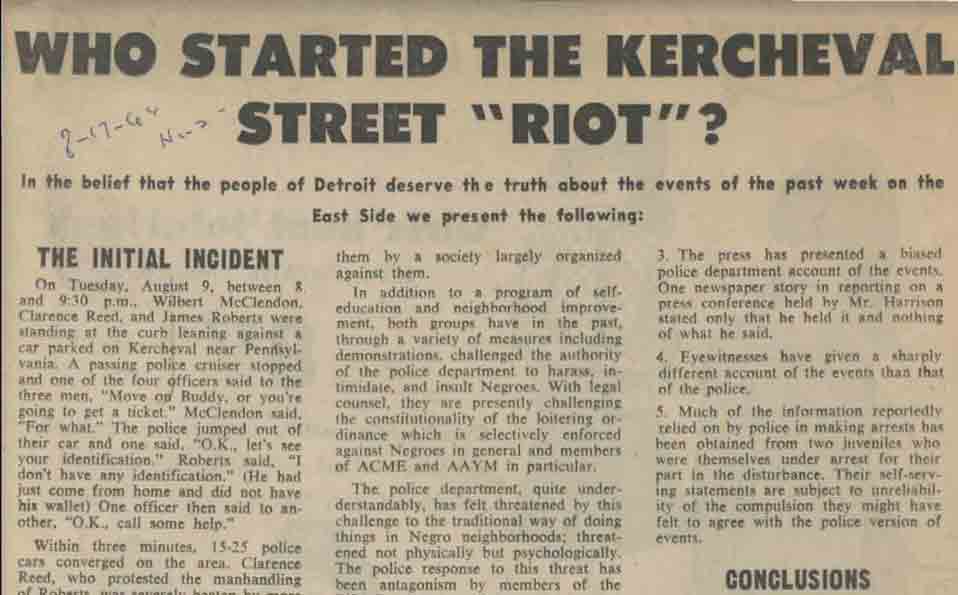

In 1966, this continuous terrorism and growing anger culminated in an event known locally as the Kercheval Incident. The Kercheval incident began when police attempted to move several black teenagers off a corner and send them home on an August night. When the young men responded by telling the police that they were already home, police called for backup. The young men and a handful of neighborhood residents then started throwing bottles at police officers and passersby, yelling, “this is a riot” and “black power.” The Detroit Police Department quickly deployed the Tactical Mobile Unit and between 150-175 police arrived on the scene and remained for three days. From August 9th-11th, storefront windows were broken, several stores were firebombed, a grocery store was looted, cars were burned, young blacks threw stones and yelled at police officers, and young blacks beat a white man all along a mile-long section of Kercheval on the East Side. Several were injured and fifty-five people were arrested. According to the Detroit Free Press, the Police also seized Molotov cocktails and “an arsenal of weapons.”

In the wake of the incident, it became clear that black resistance to police brutality was going to continue. “The police have been fucking the people too damn long,” one black man in the area told a reporter, adding that he could not stand in the street without being harassed. Another said, “Everybody’s working around here that wants to work, so that’s not the problem. But you get through working and come home and there’s nothing else to do, so you go outside and [the police] chase you off your own streets.” When asked if community organizations caused the outbreak, one man said, “Hell no, this thing’s been building for 10 years.”

Black Detroiters were mad at the mayor, at the police, mad about urban renewal and had little willingness to be docile. “Man, they steal my house, put peckerwoods in it, then tell you to move to some worse house. I’m tired of running, tired of being pushed.” Another chimed in, “Look at that bayonet on that cop’s gun. Man, I’m buying a 16 gauge with my whole pay Friday.” A 24-year-old man, James Roberts, closed the group interview saying, “The whole thing in a nutshell is that we’re trying to raise hell enough so they’ll do something, ‘cause they’ve been fucking us too damn long.”

Under these conditions, many blacks believed it was only a matter of time before an outbreak larger than Kercheval Incident occurred. In July 1967, that outbreak occurred, not surprisingly, after a rather routine police procedure broke black Detroit’s back.

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967, East Lansing, MI, Michigan State University Press, 1989

Max Herman, Summer of Rage: An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots, New York Peter Lang, 2013

Clip from a 1988 interview with Detroit activist Ron Scott, in which he describes a childhood encounter with the Detroit Police Department. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

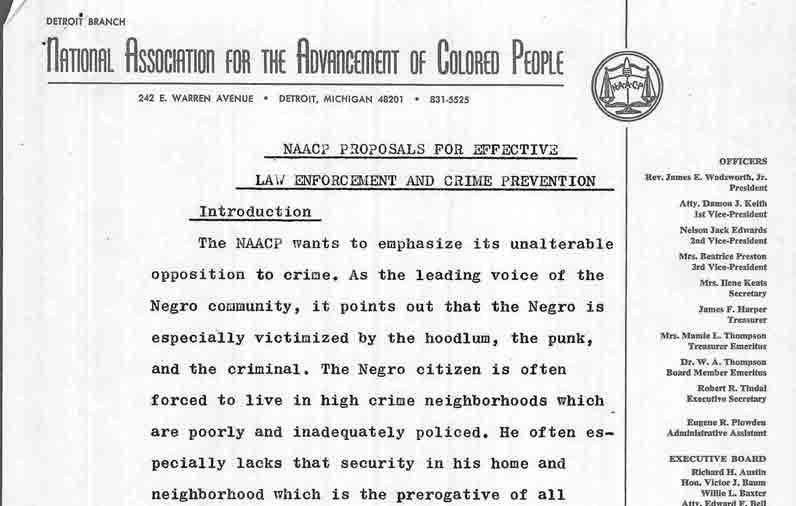

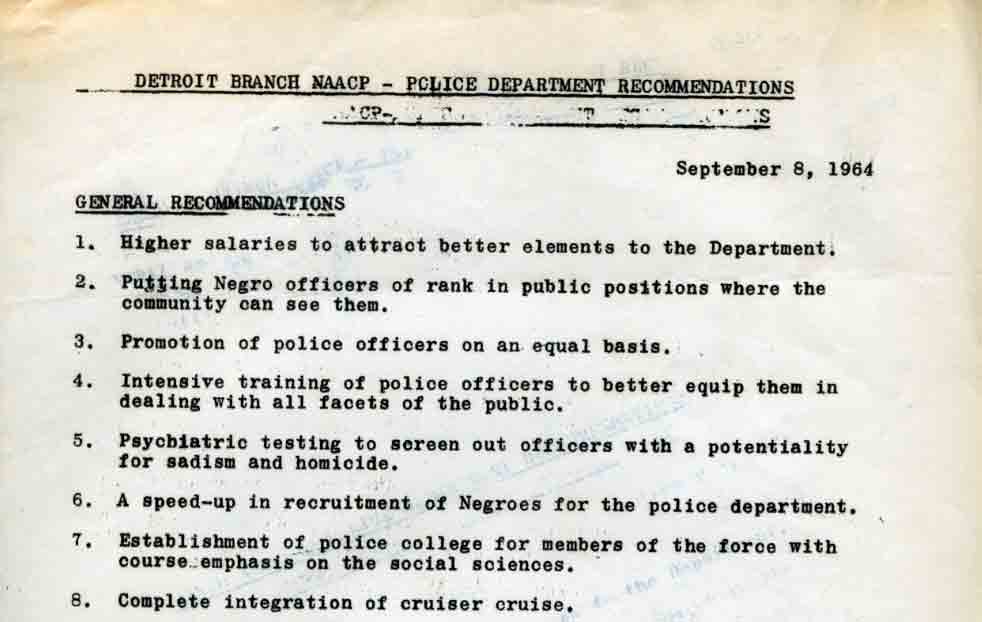

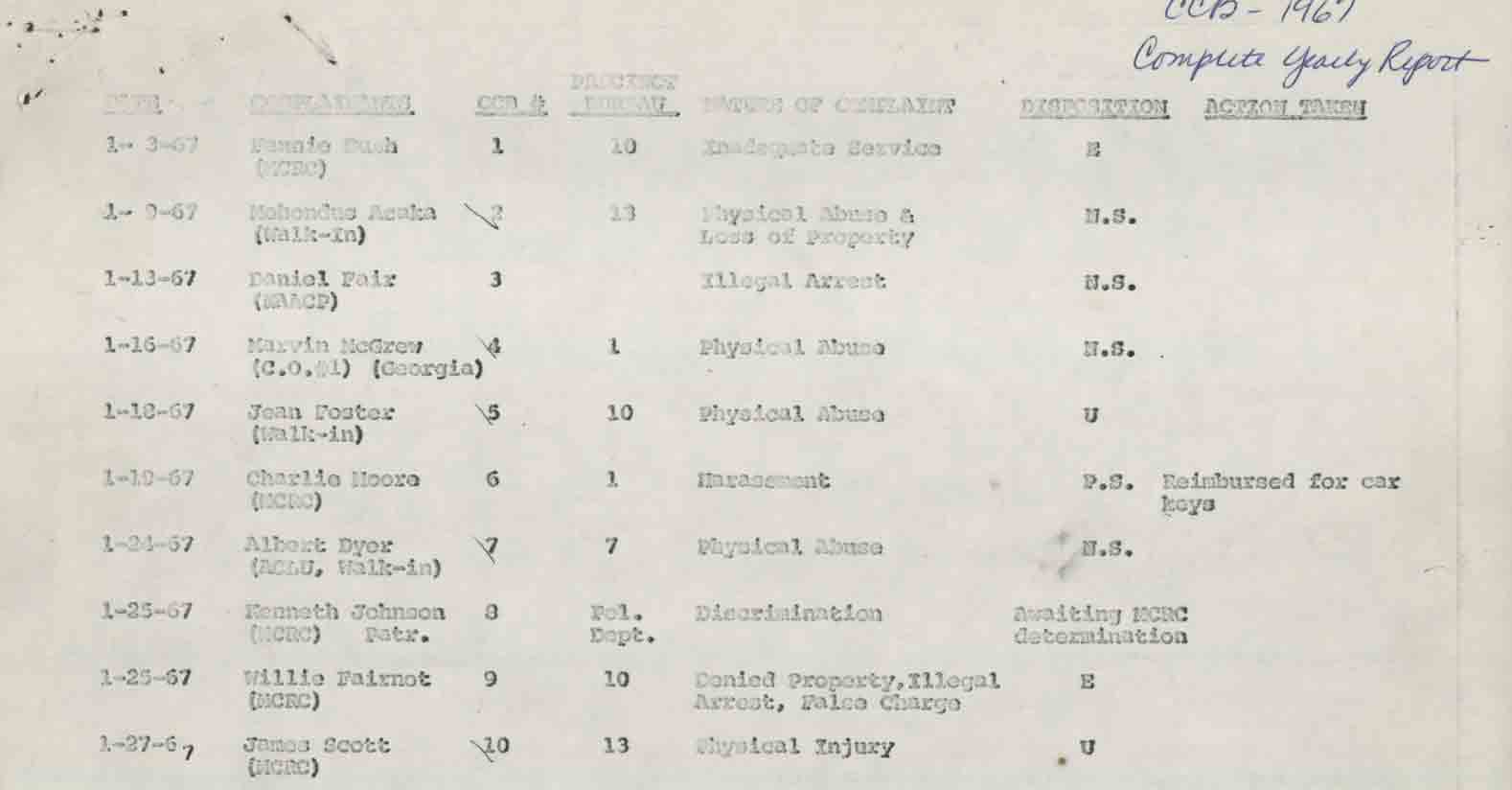

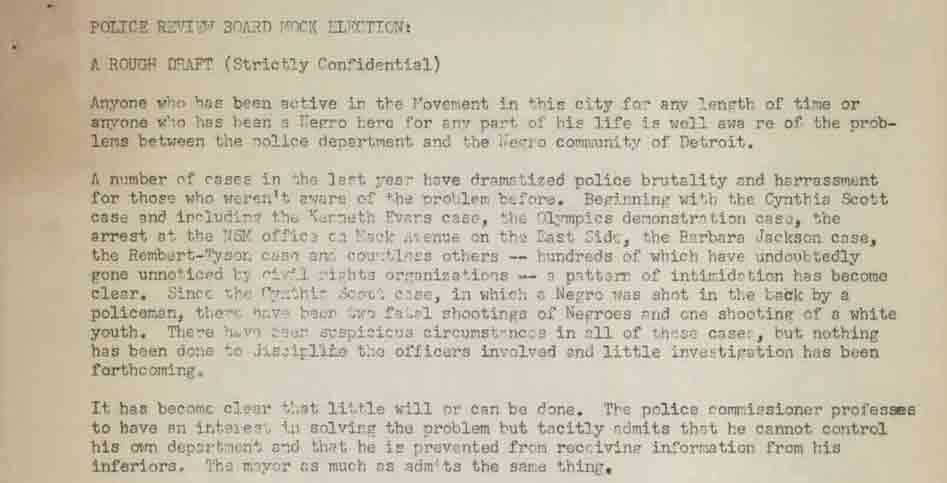

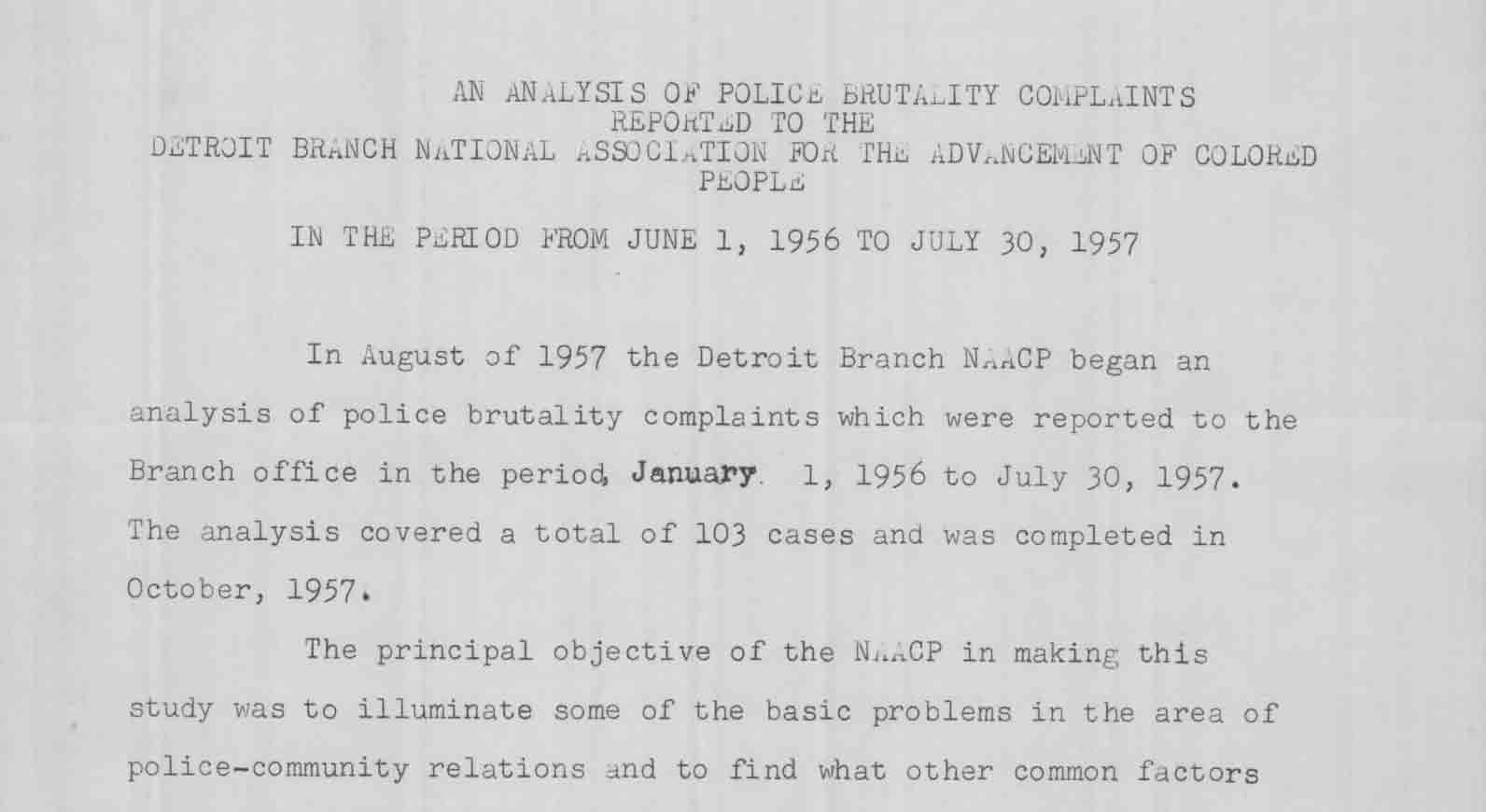

The Detroit Branch NAACP conducted an analysis of police brutality complaints they received between January 1, 1956 and July 30, 1957. They hoped the resulting study would inform the public and officials of the extent of the problem and the contributing factors. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

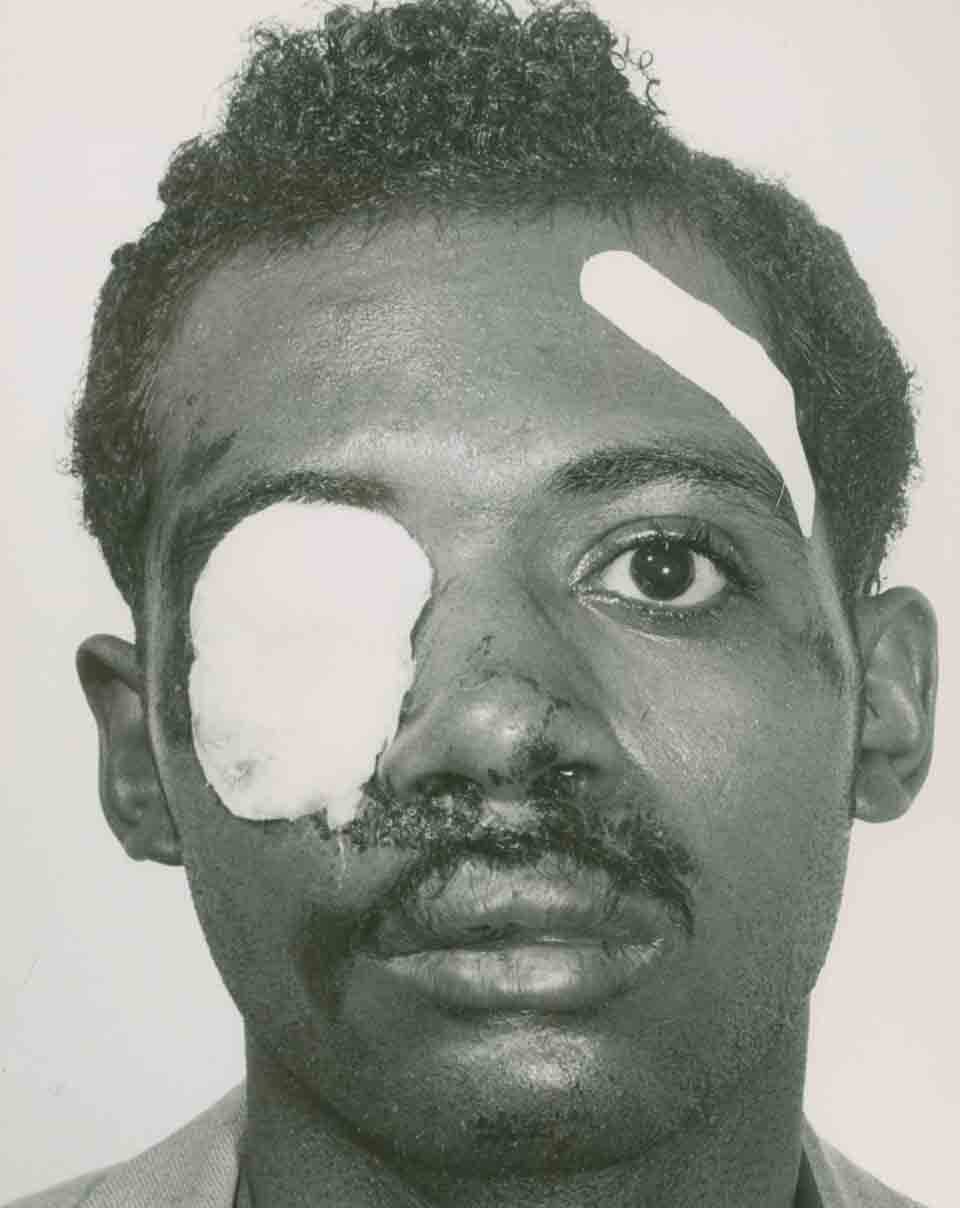

A photo demonstrating the injuries suffered by a victim of police brutality, taken as evidence by the Detroit branch of the NAACP. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clips from 2018 interviews with Elliott Hall, JoAnn Watson, Dan Aldridge, and Charles Ezra Ferrell, in which they discuss policing and Detroit’s Black community in the 1960s. –Videography: 248 Pencils

A crowd protests police brutality on July 15, 1963 following the fatal shooting of Cynthia Scott by Detroit Police. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

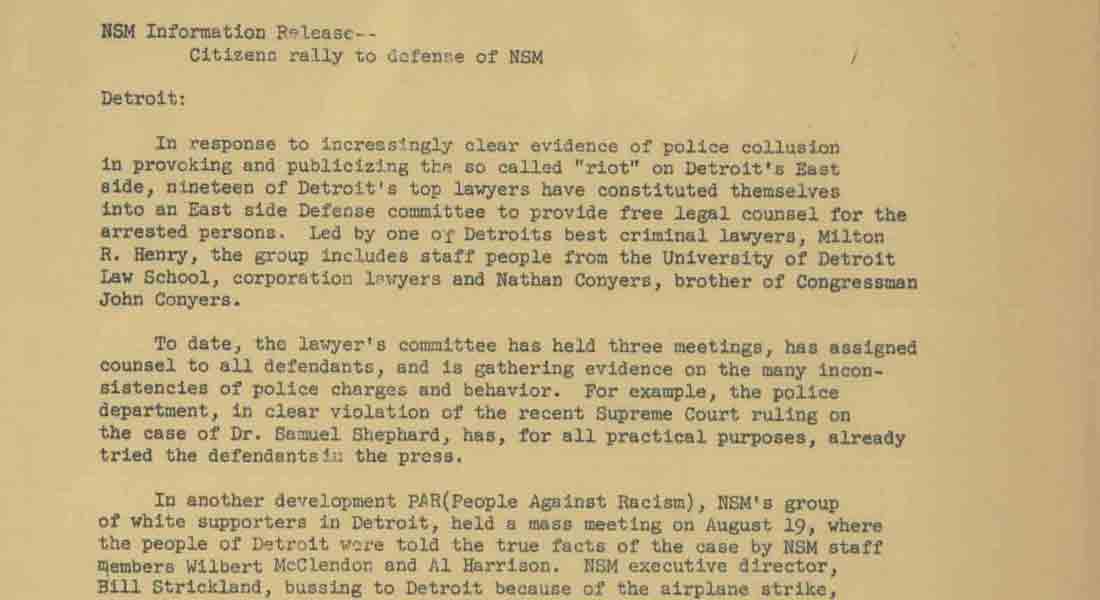

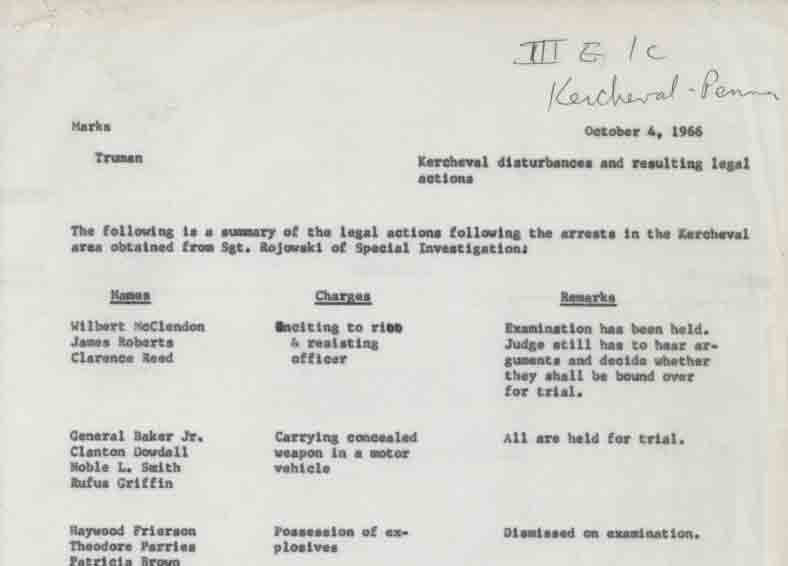

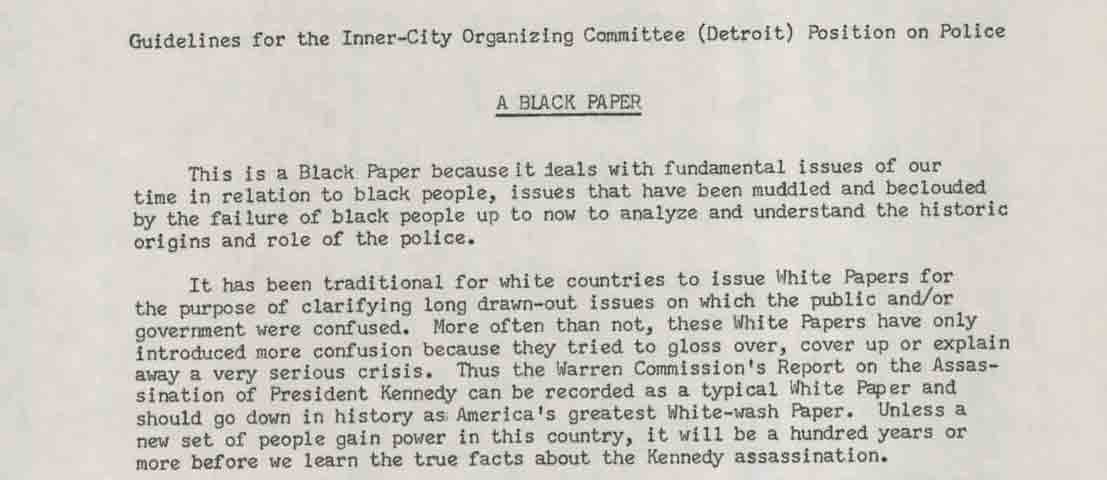

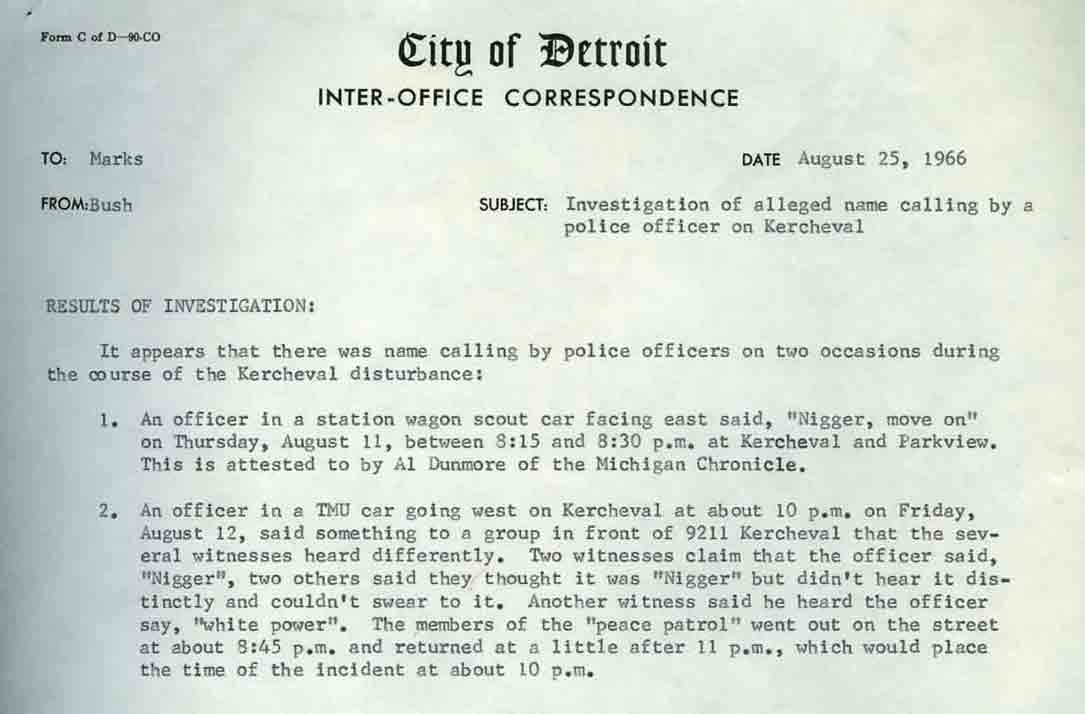

A memo from James Bush of the Detroit Commission on Community Relations to Richard Marks outlines an investigation of Detroit Police officers who reportedly harassed Black youth on Kercheval Street, leading to confrontations between police and Black residents. August 25, 1966. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clips from 2018 interviews with Elliott Hall, JoAnn Watson, Dan Aldridge, and Charles Ezra Ferrell, in which they discuss policing and Detroit’s Black community in the 1960s. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Explore The Archives

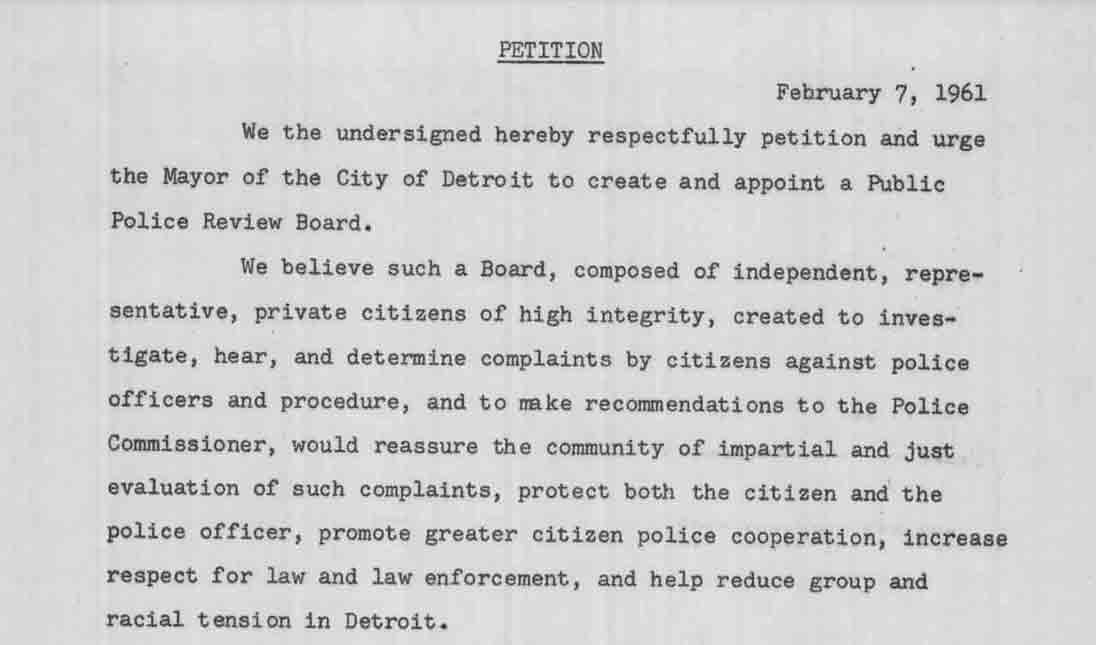

NAACP Petition to the Mayor for an independent Public Police Review Board, February 7, 1961. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University