Outcomes and Impacts

On the first Sunday following the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, Albert Cleage told his congregation that the rebellion created an opportunity for black people. As President Johnson called on people to pray for racial peace, Cleage told his church to pray for the strength to harness black Detroit’s power. From the pulpit, Cleage told parishioners to pray “for our own spirit that we may not grow weak. That we may not, in the face of difficulty, turn back. That we may not become frightened, that conflict may not make of us Uncle Toms.”

Cleage told his congregation that, “black people didn’t need a national organization” or “Stokely Carmichael” to tell them that stores that overcharged had to be gotten rid of. He said that due to the work of black power activists in Detroit, storeowners and elected officials had already been given plenty of chances to listen before the rebellion, and because they chose not to listen, black people had taken matters into their own hands. Consequently, black Detroiters now knew whites “won’t listen to a non-violent approach.”

Cleage believed the time was right for black people to assume control of the ghetto and political control of the city. He closed by saying, “But this whole thing means that either the white folks downtown understand that the whole mood has changed; that we are going to be free. We are going to be free and that they have to do certain things, and if they realize that, that’s going to save a whole lot of trouble. If they don’t realize that, there’s going to be a whole lot more trouble.

As Cleage and members of Central Congregation prayed to harness black Detroit’s power, the city’s leadership was trying to prevent more destruction. “I have got to talk to different leaders from now on,” Mayor Cavanagh declared, because the black civil rights leadership he relied on, “didn’t even know the people in the streets.” As Cleage’s members prayed, “the people in the streets” were declaring that if whites did not now listen to blacks, then they would “burn this whole stinking town down.” The city wanted to appease these people before they made good on these threats.

To begin working with black leaders who understood the pulse of the rebellion, Governor Romney, the Cavanagh administration, and Detroit’s business class quickly created a blue ribbon New Detroit Committee (NDC). J.L. Hudson, president of Detroit’s largest department store, chaired the committee.

Hudson “recognized, welcomed, and encouraged” militant blacks to fully participate in the work of the New Detroit Committee and thought each group could reach some common ground toward rebuilding the city. The committee was, “in a mood to recognize and welcome” militants, Hudson said. “We want to work with them as quickly as possible… we’re not playing games. We’re deadly serious about working with this group.” Hudson reached out to two militant organizations, the Inner City Organizing Committee and an interracial group advised by Saul Alinsky, the West Central Organization (WCO).

Cleage’s boldness and the city’s desire to work with militants illustrate clearly the immediate impact of the Rebellion on the city. After the Kercheval Incident a year prior, the mayor excluded all black power leaders from a meeting with civil rights leaders to address the concerns of black community. Following the Rebellion, however, the city was forced to deal with revolutionaries like Cleage and many others who had outpaced the more moderate civil rights leaders to become the voice of black Detroit.

Sensing that the creation of the New Detroit Committee signified a shift in power relations between blacks and the city’s business and political class, Detroit’s black power leadership began experimenting with all kinds of strategies and tactics to take advantage of this shift and achieve political control over the city.

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Clip from a 1988 interview with Detroit activist Ron Scott, in which he explains how Black political consciousness changed in Detroit 1967. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Clip from a 1989 interview with Detroit resident Herb Boyd, in which he describes how the 1967 Detroit Rebellion changed the political landscape and struggles for civil rights in the city. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

Memo from Richard V. Marks to Richard Strichartz regarding the city’s long-term plans for restoration and redevelopment after the rebellion. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The New Detroit Committee’s first official group portrait, taken at Wayne State University in October 1967. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives

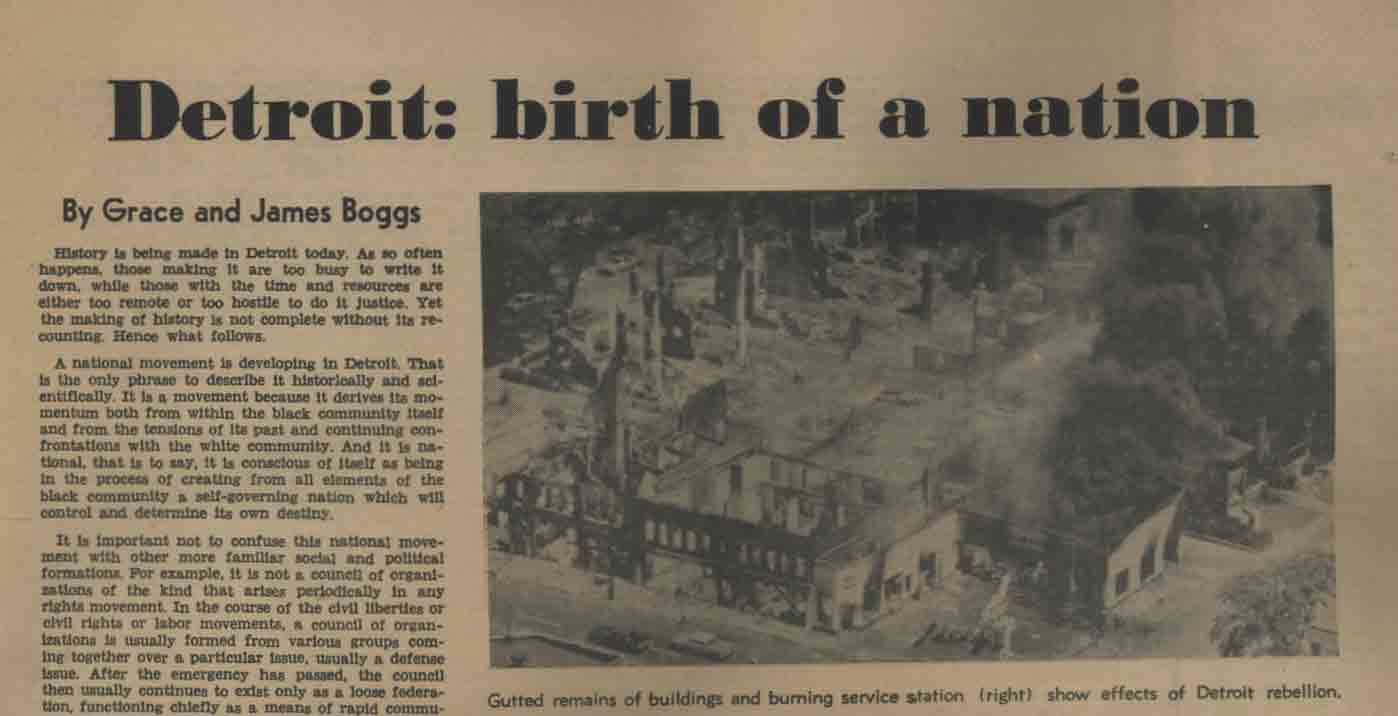

Article by Grace and James Boggs on the movement developing during the aftermath of the Detroit rebellion (National Guardian, October 7, 1967). –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clip from a 2018 interview with veteran Detroit activist Frank Joyce, in which he explains how white communities reacted to the 1967 Detroit Rebellion and the lasting impacts of these actions. — Videography: 248 Pencils

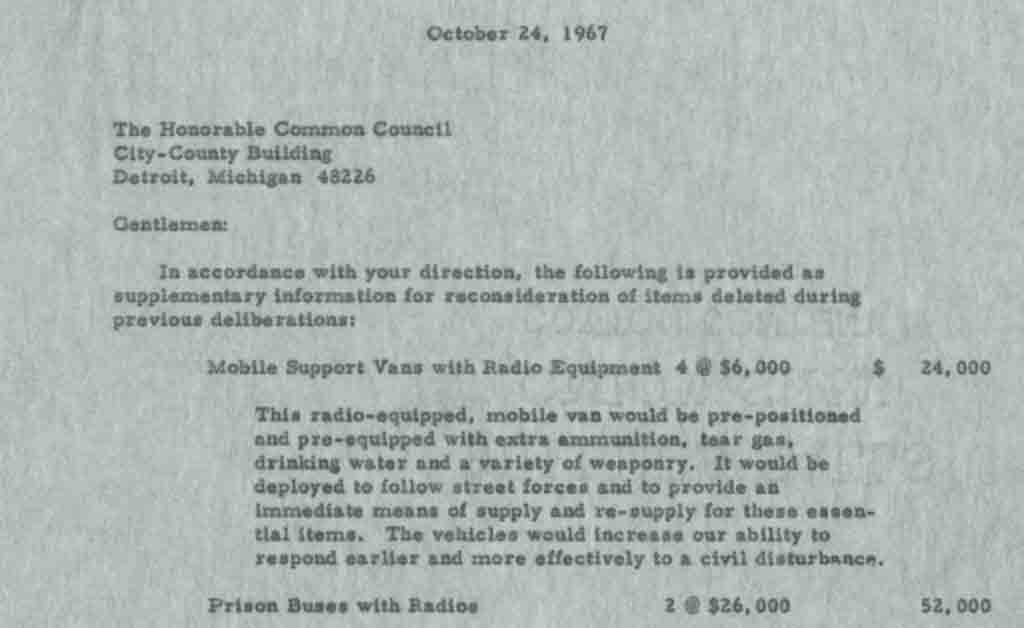

Police Commissioner Ray Girardin compiled a list of items that he felt should be purchased to enable the Detroit Police Department to better respond to Civil Unrest. This report was dated October 24, 1967 and delivered to the Detroit Common Council. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Mayor Cavanagh’s office recieved these reports, recommendations, and memoranda regarding the need for housing created by the Civil Unrest. Senders include the Community Renewal Program and the Detroit Housing Commission. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

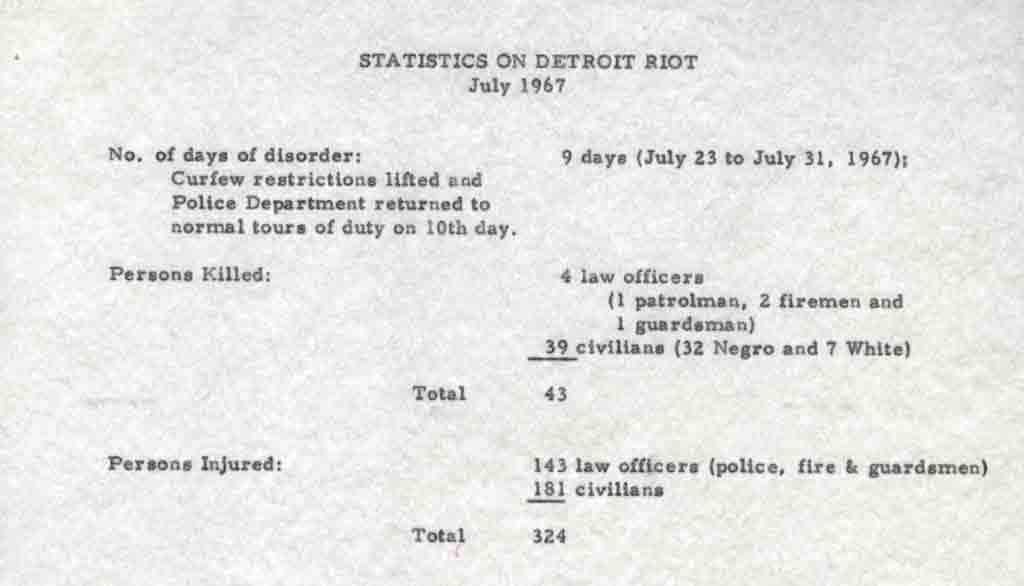

These statistics on the 1967 Detroit Rebellion were compiled shortly after the troops finally left the city and delivered to the Mayor’s office. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.