Forming the Federation for Self-Determination

Forming the Federation for Self-Determination

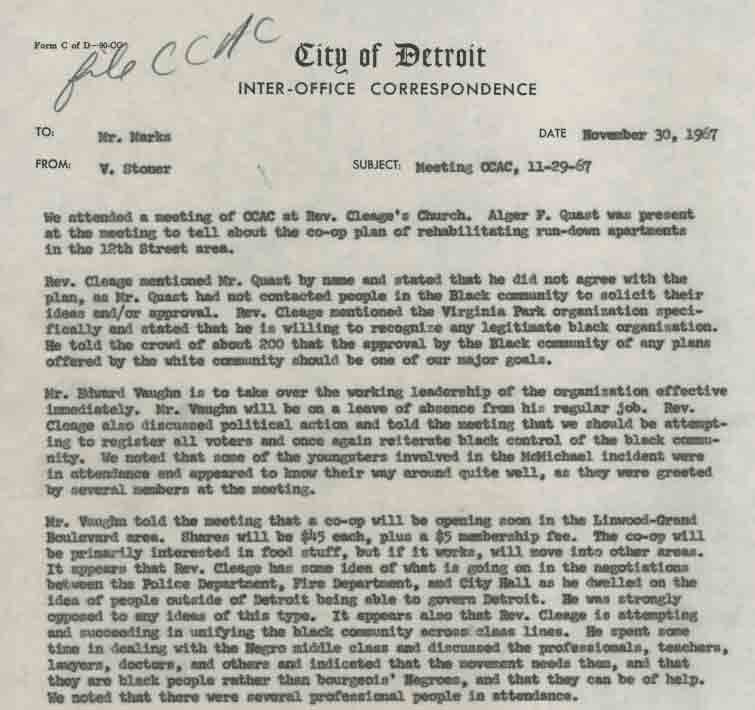

Formed in late 1967, the Federation for Self-Determination (FSD) was basically the financial arm of the Citywide Citizens Action Committee (CCAC). So that the CCAC could undertake large-scale reconstruction programs, they decided to also accept private dollar and established the FSD to establish political control over the money. White investors could only invest with “a clear recognition that” ownership of entities invested in would pass from the hands of white investors to the black community “over a reasonable period of time.” The CCAC applied this same principle to money from the federal government and the FSD was to serve as an umbrella organization allowing this principle to be applied to black power organizations in Detroit at-large.

While the CCAC was an organization made up of individuals, the FSD was made up of multiple organizations. Not only conceived of as an economic umbrella, it was also created “to bring about unity in the inner-city, providing a forum for discussion and making the decisions of the day.” Rev. Albert Cleage, Jr. was elected chairman and Lorenzo Freeman of the WCO was named vice chairman. Other organizational representatives included Grace Lee Boggs, Ken Cockrel, Dan Aldridge, and Congressman John Conyers. It was to function as a forum for “gathering, exchanging and disseminating information,” and to keep a database of black power organizations and service providers.

With this database they planned to serve as a referral agency for funders and the city departments who wanted to contract black organization for reconstruction projects. By connecting community programs with funding agencies, the FSD planned to become a means to maintain black unity and “strengthen the black community’s position when seeking external funding for its economic development programs.” In December of 1967, the FSD submitted a three-phase proposal to the New Detroit Committee (NDC) for a total of $536,000 over three years.

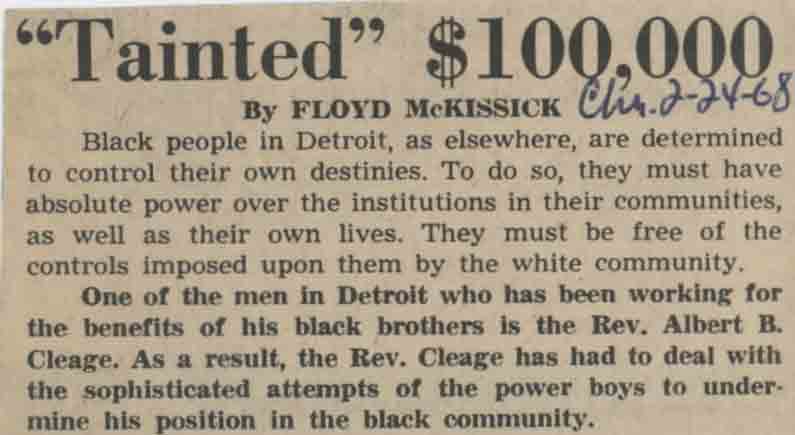

The NDC offered the FSD $100,000 and stipulated that the money could not be used for political activity. At a press conference, Cleage declared, “We are not for sale. New Detroit can keep its ‘strings attached’ money. Black people are in the midst of a national black revolution. The objective of the black revolution is self-determination. Self-determination means black control of black communities. This involves every area of the black man’s life, freedom from white controls, and the dignity which comes from the knowledge that we are deciding our own desires.”

Their rejection of the money brought the FSD national attention and, from the perspective of Detroit’s black power leadership, further united black Detroit and bolstered the FSD’s local leadership by exposing the NDC as an agent of city and state co-optation. Floyd McKissick of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) saw the Federation’s rejection of the funds as key to protecting the integrity of black people and Robert Allen wrote that the rejection of Ford Foundation money was a successful strategy to counter the foundation’s growing attempt “to penetrate militant organizations which were believed to wield some influence over the angry young blacks of the ghetto.” Dorothy Dewberry of Detroit Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) called the Foundation’s offer a form of “corporate Imperialism,” and Ken Cockrel, who also approved of the rejection added, “That little bit of bread isn’t going to do us any good.” Based on these local and national responses, Cleage believed that turning down the money “white folks had offered seemed to unite black folks as we have never been before. Down through the years they figured that money could buy anything. After all, white folks have been buying and selling black people since the days of slave ships.”

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

David Goldberg, “Community Control of Construction, Independent Unionism, and the ‘Short Black Power Movement in Detroit,” Black Power at Work: Community Control, Affirmative Action, and the Construction Industry, Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2010

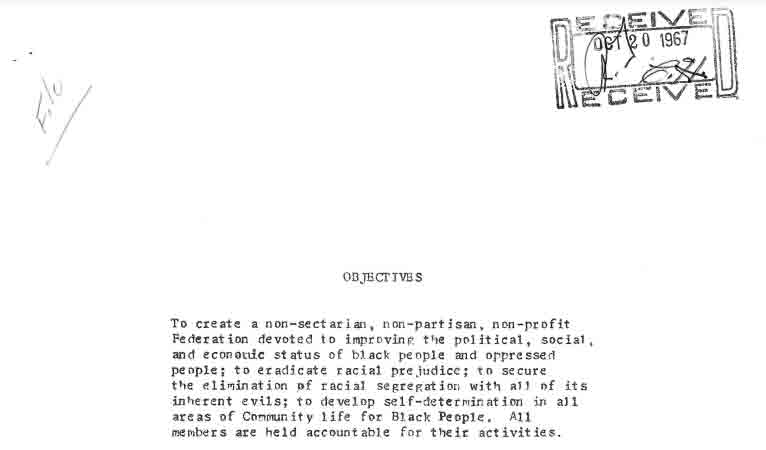

Founding document of the Federation for Self-Determination, approved at a meeting on October 12, 1967. The document outlines the objectives, membership, assembly, and coordination of the organization. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

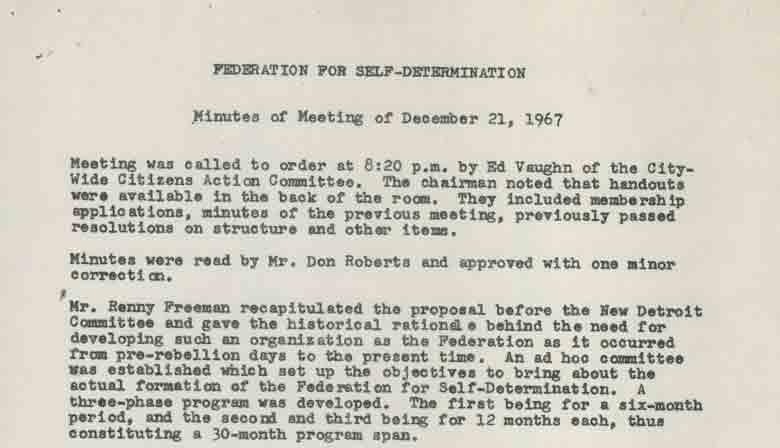

Federation for Self-Determination, Minutes of Meeting of December 21, 1967. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

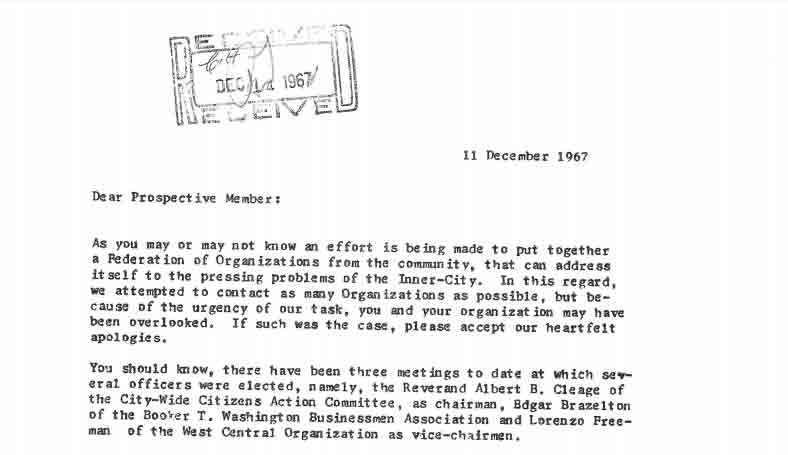

Letter from Rev. Albert Cleage, Jr. to prospective member of the Federation for Self-Determination, December 11, 1967. The letter describes the first three meetings of the Federation and explains the importance of joining the coalition-based organization. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clipping, \”\’Tainted\’ $100,000\” (February 24, 1968). The Rev. Albert B. Cleage turned down the offer of $100,000 from the newly-created New Detroit Committee, citing restrictive conditions. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives

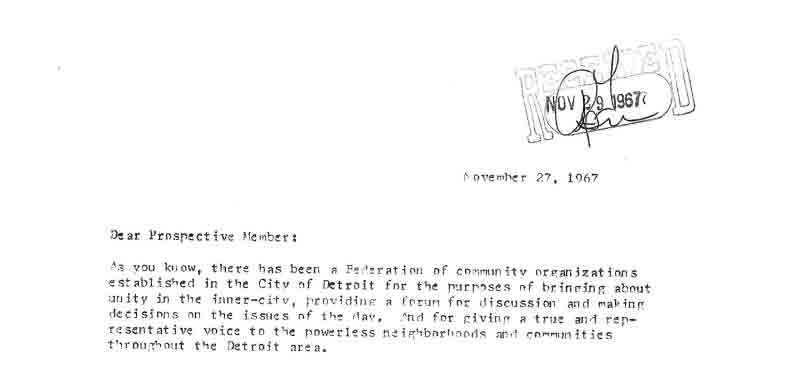

Letter from Rev. Albert Cleage, Jr. to prospective member of the Federation for Self-Determination, November 27, 1967. The letter served as an invitation to a General Assembly of community organizations to form the Federation for Self-Determination. Cleage described the event as \”the most important meeting that has ever before been held in the inner-city.\” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

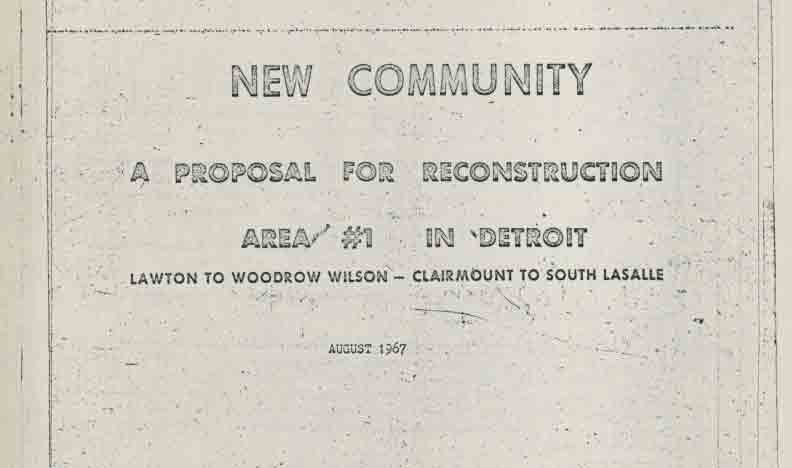

Richard B. Henry and Henry L. King of the Malcolm X Society produced this post-uprising proposal for an independent Black cooperative in August 1967. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

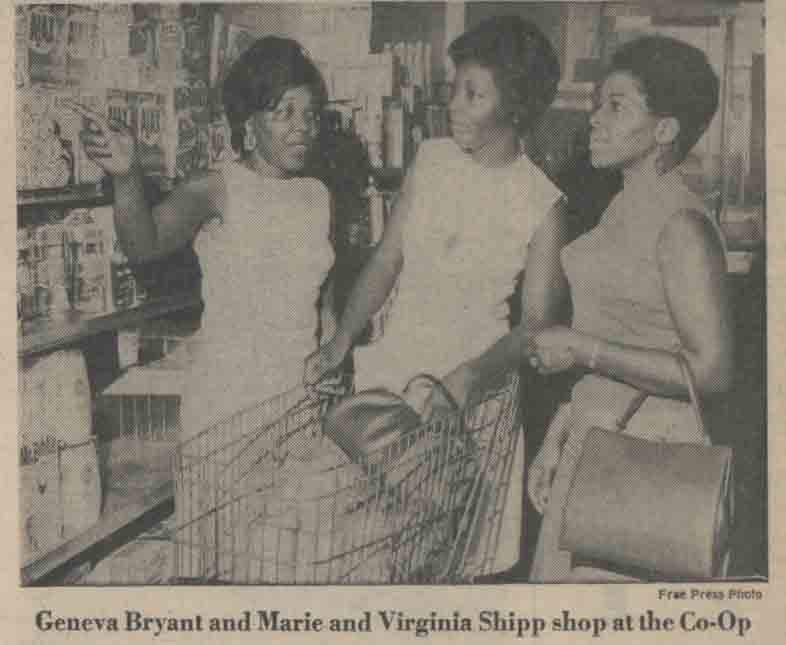

In addition to The Black Star Co-Op Market, the Black Star Clothing Company and the Black Star Shell Service Center gas station were businesses run by Black for Blacks. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.