Self-Determination and Urban Redevelopment

The Formation of the Citywide Citizen Actions Committee

The Citywide Citizens Action Committee was formed the day before the New Detroit Committee was scheduled to meet for the first time and became the city’s first mass black power organization. At a meeting with reported attendance ranging from 300 to 1000 and organized by a wide swath of black power figures, Rev. Cleage was elected chairman of the organization and Glanton Dowdell, a member of Uhuru/RAM was named co-chair. The CCAC contained all the elements of Detroit’s established black power leadership including Grace Lee Boggs, the Henry Brothers, and Kenneth Cockrell who had become associated with members of Uhuru/RAM and had been involved with the Inner City Organizing Committee. The CCAC was a popular front organization uniting different philosophical strands of black power in Detroit. According to Milton Henry, the CCAC included, “some moderates, some not so moderate, a few who are a little radical, and others who are just plain out of sight.”

At this first meeting, they formed committees devoted to legal issues, education, finance, communications, redevelopment, civil service, political organization, ministerial relations, consumer’s control, and poverty programs. Cleage declared at the meeting, “We are the new black establishment, the Toms are out. New Detroit will take orders from us.” In response to the meeting, Robert Kornegay, president of the Detroit Urban League, privately told Henry Ford II civil rights and moderate black leaders were “scared to death to stand up and be counted.” He told an audience weeks later, “There is no such thing as a moderate any more—only militant and more militant.”

To Detroit’s black power leadership, the emergence of the CCAC was evidence that Detroit’s black movement had entered a new phase. “History is being made in Detroit today,” declared James and Grace Lee Boggs. “A national movement is developing in Detroit. That is the only phrase to describe it historically and scientifically. It is a movement because it derives its momentum from within the black community itself and from the tendencies of its past and continuing confrontations with the white community. And it is national, that is to say, it is conscious of itself as being in the process of creating from all elements of the black community a self-governing nation which will control and determine its own destiny.”

They distinguished the CCAC from previous organizations because it was neither coming together over a single defensive issue or a coming together of previously existing blocs of people. It was a national movement because its body represented what they believed was a new black nation coming into birth. According to the Boggses, for blacks, the rebellion, “severed the psychological ties which still bound the majority of employed Negroes to white society,” and freed them to create a new nation.

The CCAC conceived of itself as a vehicle to confront the white community with “one voice with one program, forged out of our common oppression as black people and out of the needs and talents of us all.” The goal of the CCAC was “self-determination for the black community or the transfer of power from the white community to the black community.” The CCAC demanded the transfer of political power to the black community through the establishment of ward-based elections rather than citywide elections. They also demanded that the NDC serve in an advisory capacity to the CCAC, that Governor Romney issue an executive order for equal opportunity, that all business and housing loans for reconstruction be referred to NDC, a reorganization of anti-poverty programs allowing the poor to run their own programs, and a redistricting plan brought to the Board of Education by the Governor and Mayor.

The CCAC believed that the city’s fear of another rebellion would encourage the city’s business and political class to meet their demands. Consequently, the CCAC strategically tried to keep whites in constant fear that another rebellion was imminent while keeping black anger high enough to validate the white community’s fears. This strategy required the CCAC to utilize tactics that would simultaneously scare whites, exacerbate black anger, and create the kind of unity amongst blacks that would prevent “any black man to cross a black picket line anywhere at any time. We mean the kind of unity which will make it possible to merely publish the name and address of any store which is off-limits to black people because of racial discrimination and know that no black man will dare enter that store.”

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Sidney Fine, Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967, East Lansing, MI, Michigan State University Press, 1989

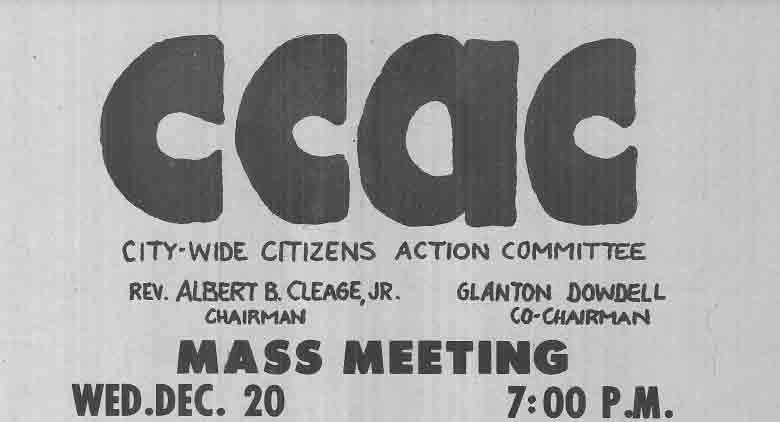

City-Wide Citizens Action Committee flyer, 1967. The CCAC was led by the Reverend Albert B. Cleage, noted political and religious activist who launched the Black Christian National Movement in 1967. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

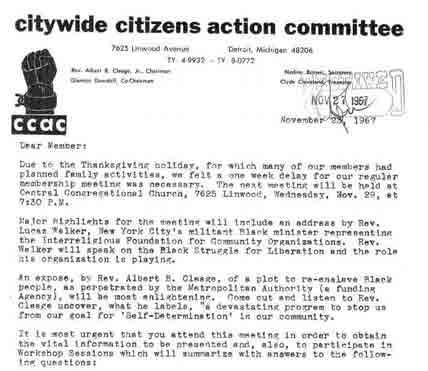

Letter from Rev. Albert Cleage, Jr. and Nadine Brown to members of the Citywide Citizens Action Committee, November 23, 1967. The letter announces an upcoming meeting featuring Rev. Lucius Walker of IFCO and workshop sessions led by Committees on Labor and Employment, Education, and Poverty. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Interview with Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman (Rev. Albert Cleage), late December 1967/early January 1968. In the interview, Agyeman offers his analyses on self-determination and community control of resources in Black communities. –Credit: Paul Lee

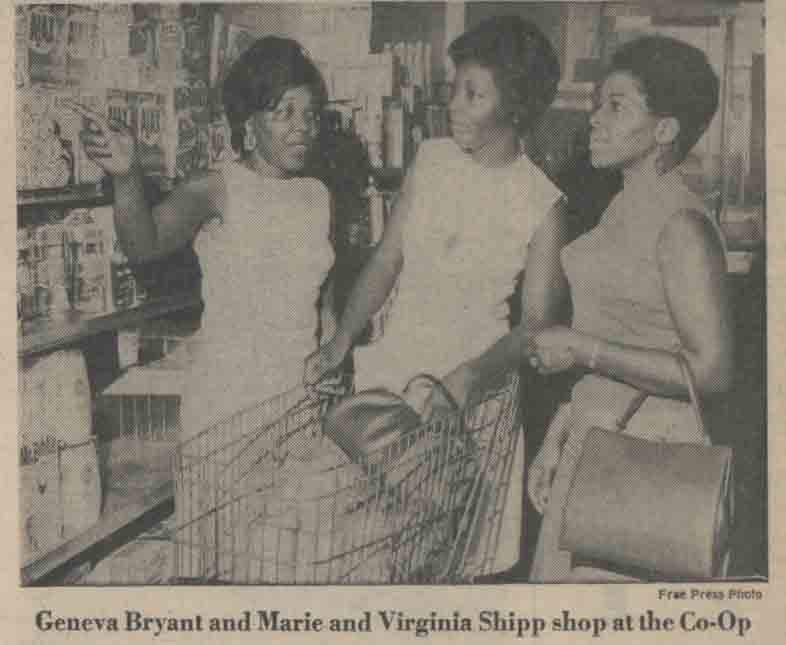

After the rebellion of 1967, the Citywide Citizens Action Committee focused on community organization and economic development, including a Black cooperative movement. Credit: Edward Vaughn Papers, Box 3, Folder 36, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives

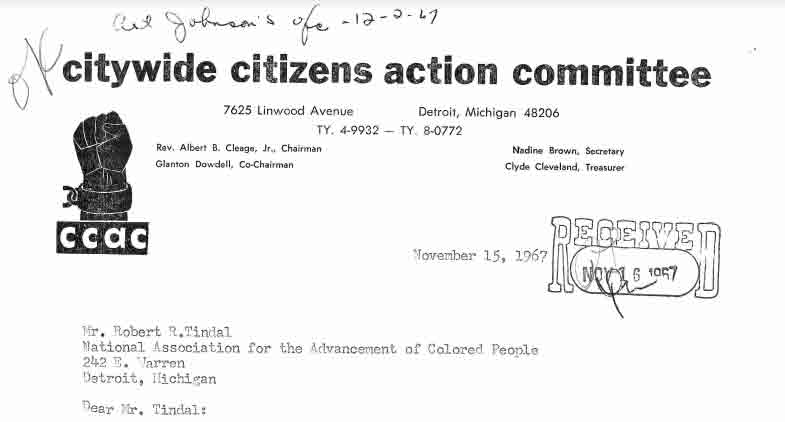

Letter from Rev. Albert Cleage, Jr. of the CCAC to Robert Tindal of the Detroit NAACP, November 27, 1967. The letter announces an upcoming meeting of black school administrators and community representatives to discuss ways to work collaboratively to improve education in Detroit. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Flyer for a mass meeting of the City-Wide Citizens Action Committee, featuring Rev. Lucius Walker, Jr. of the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization. The meeting was held on December 20, 1967 at Rev. Cleage\’s Central United Church of Christ. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

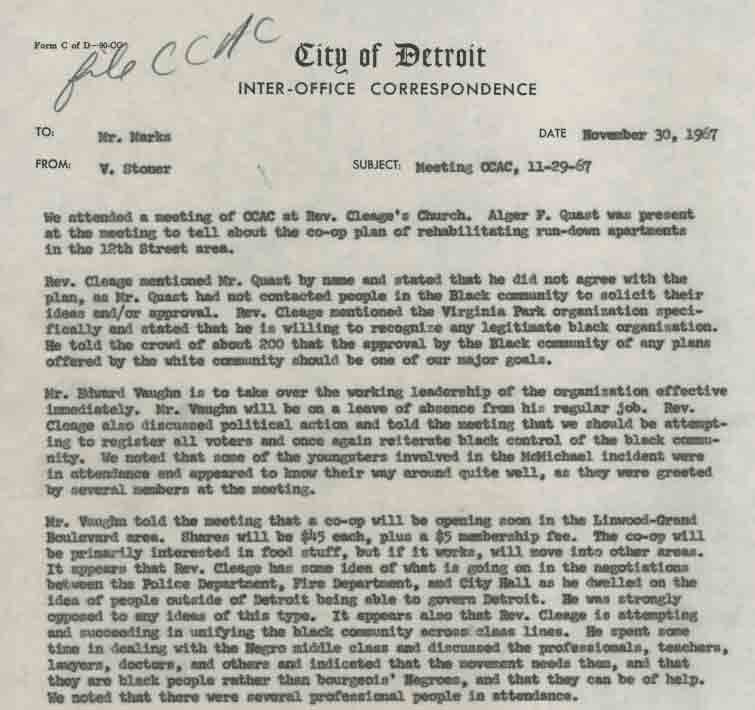

In this internal memo from City of Detroit employees V. Stoner to Mr. Marks (November 30, 1967), Stoner discusses the previous day\’s City-Wide Citizens Action Committee meeting. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

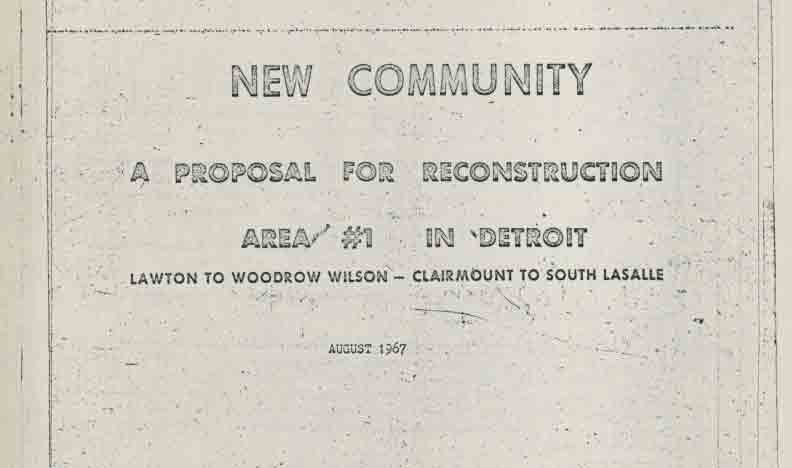

Richard B. Henry and Henry L. King of the Malcolm X Society produced this post-uprising proposal for an independent Black cooperative in August 1967. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.