Postwar Organizing

Having organized successfully to desegregate the United Auto Workers (UAW), Black workers in Detroit had a highly developed set of organizational skills that allowed them to effectively organize after the Second World War. Following the war, Black Detroiters were prepared to fight for the equality at home that they had fought for overseas. While some organizations that had existed before the war made tremendous contributions to this struggle, new more radical organizations also emerged. At the center of this Black organizing was a liberal labor-civil rights coalition.

Because the city eliminated ward-based elections in favor of at-large local elections—likely to prevent Black voters from electing their own representatives to the city’s common council—Detroit’s Black activists were forced to form coalitions with other groups. Because so many Black Detroiters were members of the United Auto Workers in the immediate postwar period, an alliance with labor made plain sense. As the 1945 municipal elections neared, Black communities and the UAW worked to create and support a slate of labor candidates.

To construct this slate, the Detroit chapter of the National Negro Congress and other Black organizations drafted the Rev. Charles Hill to run for city council. Hill had long been the pastor at Hartford Memorial Baptist Church, had been a member of Mayor Jefferies Interracial Committee, was active in the 1941 Ford strike, was involved in activism around the Sojourner Truth Housing Project, and was sympathetic to the city’s Left. These experiences and commitments led the Political Action Committee of the UAW-CIO to endorse Hill and make him part of a slate of white labor candidates, including Richard Frankensteen for Mayor, and Hill, George Edwards, and Tracy Doll for the city’s Common Council.

The CIO-PAC and Black organizations campaigned in both Black and white neighborhoods to elect the whole slate. Frankensteen appeared in Black neighborhoods and uplifted Hill. However, when he appeared in front of solely white audiences, he was much less vocal about his endorsement of Hill. Despite these inconsistencies, support for the labor-civil rights slate was so strong that each candidate advanced to the second round of elections after the primary.

Sensing the threat that the labor-civil rights coalition posed to his power, Mayor Jefferies preyed on fears that the slate was communist and would force the city to end racial segregation by adopting open housing laws. Jefferies red-baiting and racist fear mongering worked. Jefferies won the election but the labor-civil rights slate did well. For mayor the slate received 44 percent of the total vote, 61 percent of votes in polish precincts, 71 percent in Italian precincts, and 90 percent in Black precincts. These high numbers of votes for the labor-civil rights coalitions amongst precincts that would have never supported a slate with Black candidates only a few years prior gave Black Detroiters reason to believe a coalition with labor could be useful.

Despite its usefulness, this coalition was difficult to maintain because of growing conservatism within the country and especially because of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s campaign against communism. In Detroit, some of the most effective organizers in the UAW and some of the white organizers most committed to civil rights were also members of the Communist Party. As anti-communism spread throughout the country, the UAW purged communists from its ranks, which also made it harder for Black Detroiters to use the UAW as a consistently progressive ally. In response, Black Detroiters typically embraced a liberal integrationist approach to politics working in concert with the UAW or took the path of radicalism, joining and creating revolutionary organizations.

Liberal Black activists became involved with the NAACP, with the Urban League, but largely used the UAW as their political vehicle. The Detroit NAACP and Urban League chapters organized for both open housing and for increased employment for Blacks in Detroit. Although the passage of Executive Order 8044 increased the number of Black workers in auto plants enormously, Blacks still had a difficult time finding decent work outside of the city’s plants. The Urban League organized campaigns to get Blacks hired in grocery stores and department stores downtown, as did the NAACP. Despite these campaigns, many Black Detroiters grew increasingly frustrated with these liberal organizations leading the membership of the NAACP to plunge to 5,162 in 1952 from a height of 25,000 during World War II. Those who rejected liberal politics in favor of more radical alternatives became active in the Socialist Workers Party, Correspondence, and the Communist Party.

References:

Beth Bates, The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2012

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2007

Clips from 2018 interviews with JoAnn Watson and Charles Ezra Ferrell, in which they discuss Detroit’s history of Black radicalism in the early 20th Century. –Videography: 248 Pencils

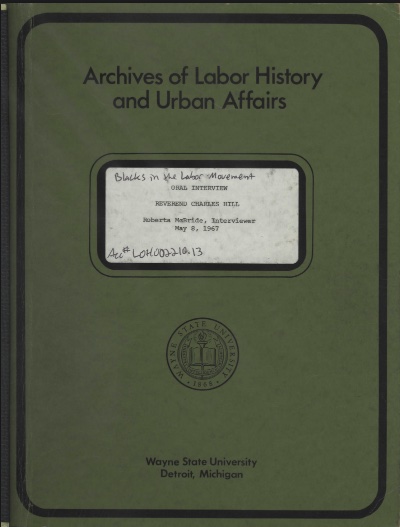

Transcript of an oral history interview with Detroit civil rights activist Rev. Charles Hill, conducted by Roberta McBride on May 8, 1967. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

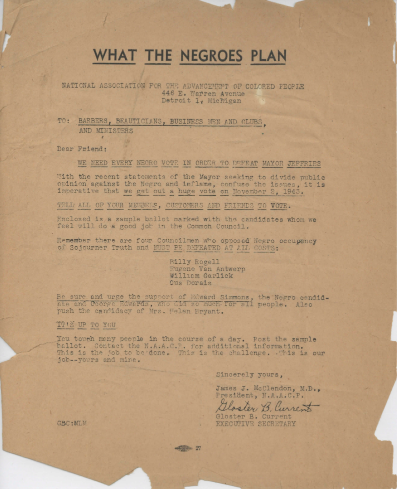

A letter from Detroit NAACP Executive Secretary Gloster Current urging “barbers, beauticians, business men and clubs, and ministers” to organize for the 1943 Common Council elections.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Explore The Archives

Members of the Detroit Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) stand outside an unidentified building in the 1940s and hold signs, that read: “The Yanks Are Not Coming–Let God Save the King!” and “No Jim Crow.” Coleman A. Young can be seen standing in the second row, second from the right.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

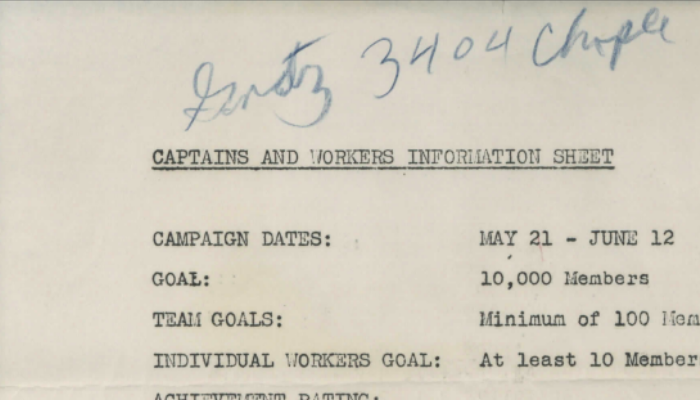

A large part of organizing a group like the NAAPC was recruiting members. In this document, the behind-the-scenes of the tedious yet crucial process of membership building is outlined.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

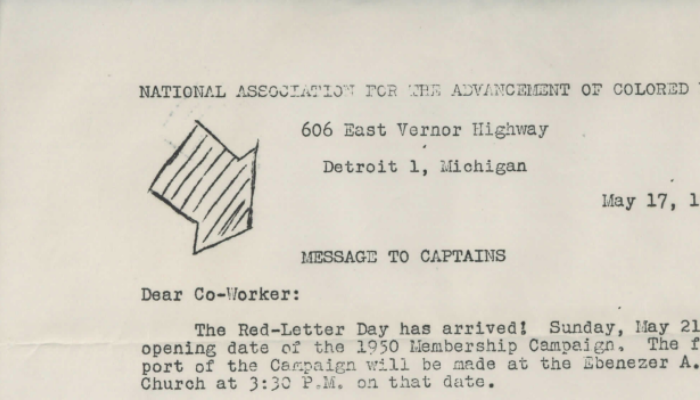

Memo from the Detroit NAACP to Captains from May 17, 1950 about that year’s membership campaign. Organizing a large organization like the NAACP required numerous volunteers, staff, and organizers. The Detroit branch of the NAACP was one of the largest and most active in the nation, and this memo provides a peek into what day to day organizing looked like.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

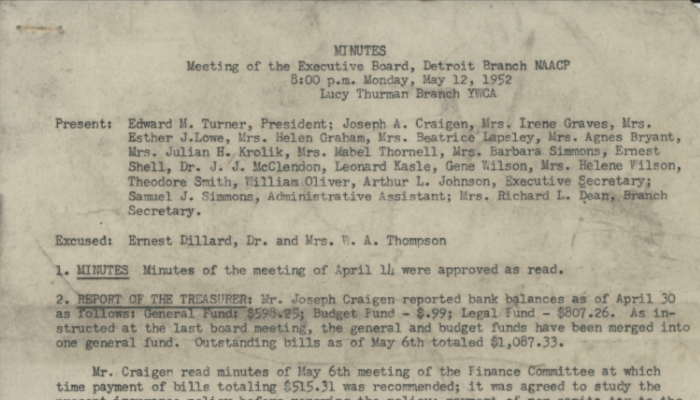

This document is the minutes for the Detroit Branch NAACP meeting on May 12, 1952. Among other things, it discusses funding and housing segregation.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

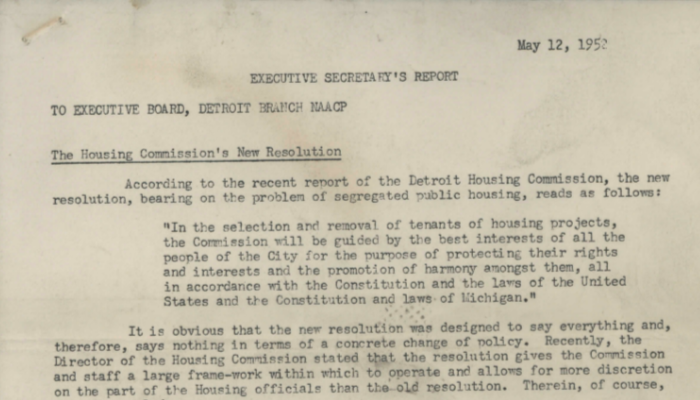

This document is a report of the May 12, 1952 meeting of the Detroit Branch NAACP, and discusses the conclusion of the housing comission among other notable topics.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

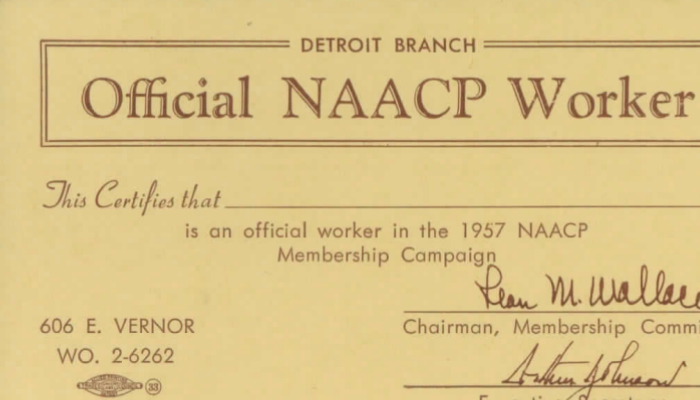

Members organizing were given cards to identify them as offical organizers of the NAACP.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

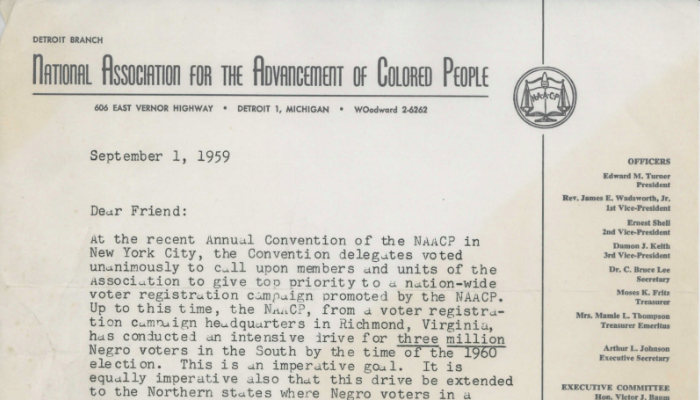

Voter registeration was a vital part of the civil rights movement. This letter by Rev. James E. Wadworth and Arthur L. Johnson dated September 1, 1959 discusses the Detroit Branch of the NAACP voter registeration programs, arguing that it will have a “far-reaching effect on the 1960 elections in this area.”–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A pamphlet published by Pioneer Publishers in 1944 titled “Negroes in the Post-War World,” by Albert Parker. The pamphlet discusses the aftermath of World War II and the reshaped postwar world for Black Americans. Detroit was transformed by the war, and life for Black Detroiters grew ever more bountiful, complicated, and tense.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

This pamphlet, published by the Civil Rights Congress, describes what the organization is, what they do, and their creed. The CRC had a major branch in Detroit.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The Civil Rights Federation played a major role in organizing in Detroit early in the 20th century. This pamphlet invites the reader to apply to the Civil Right League, a Detroit affliate of the Civil Rights Federation.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The 1937 Ford Riot in the midst of the Great Depression is detailed and discussed in this pamplet from the National Citizens’ Committee for the Protection of Civil Rights in the Automobile Industry.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

This undated study by the Detroit Urban League examines the Black and white middle class. It states that there are major disparities between them, and also notes the distance between the Black middle class and the Black working class.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

These newspaper clippings from the 1940s highlight the transformation and limits of Mayor Jeffries’ Interracial Committee. The committee attempted to aleviate racial tensions in Detroit but lacked meaningful enforcement powers. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

This reports details the activities, findings, and perscribed solutions of the Mayor of Detroit’s Interracial Committee in the 1940s.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

This reports details the activities, findings, and perscribed solutions of the Mayor of Detroit’s Interracial Committee in the 1940s.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

This reports details the activities, findings, and perscribed solutions of the Mayor of Detroit’s Interracial Committee in the 1940s.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

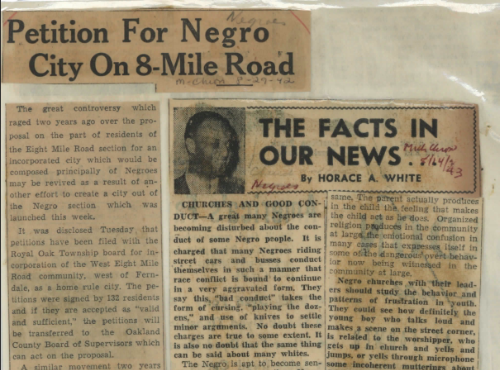

Newsclippings from the Michigan Chronicle, including two articles: “The Facts in Our News” by Rev. Horace A. White (8/14/1943) and “Petition For Negro City On 8-Mile Road” (8/27/42). -Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

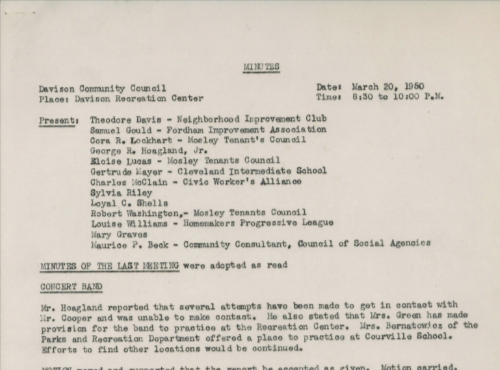

Community organizations were prominent in Detroit during the 1950s, and they served as a form of grassroots community oraganzing and democray, This specific meeting of the Davison Community Council on March 20, 1950 approves a motion that sanctions the council to write a telegram to the Detrout Common Council “urging that all available Federal funds be used for public housing and that people in slum areas be adequately housed before evicton..–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

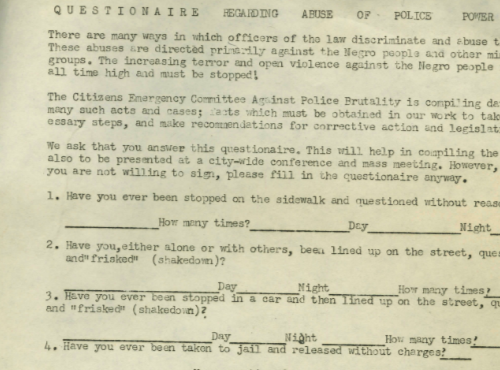

Police brutality forced the Black community to organize. Organizations held meetings, protested, wrote letters, signed petitions, and ensured greater accountability of police officers, with much of this early organizing taking place in the Black church.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

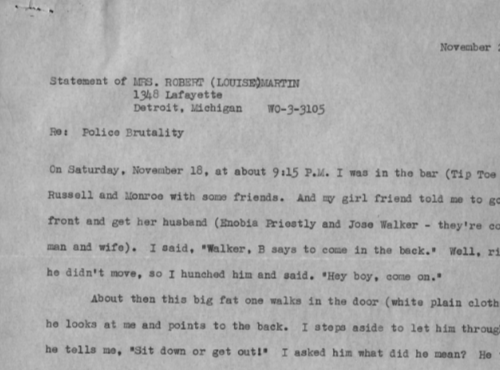

A statement given to the Civil Rights Congress by Mrs. Robert Martin on November 20, 1950. The alarming frequency of police brutality and harasement cases transgressed the limits of the built environment. Even in bars, and especially in public, Black residents in Detroit were at a constant threat from the police as this statement by Mrs. Martin demonstrates.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

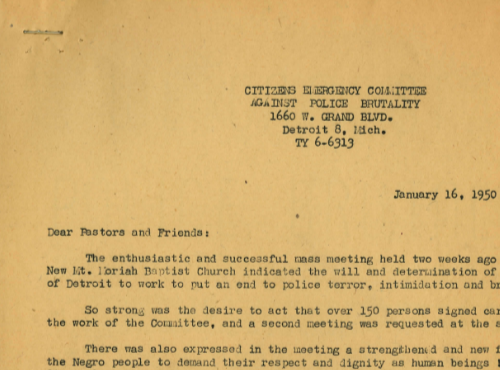

Letter from Rev. Charles Hill dated January 16, 1950 on behalf of the Citizens Emergency Committee Against Police Brutality. In the letter and flyer, Rev. Hill encourages Black Detroiters to attend an upcoming mass meeting at Greater New Mt. Moriah Baptist Church. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

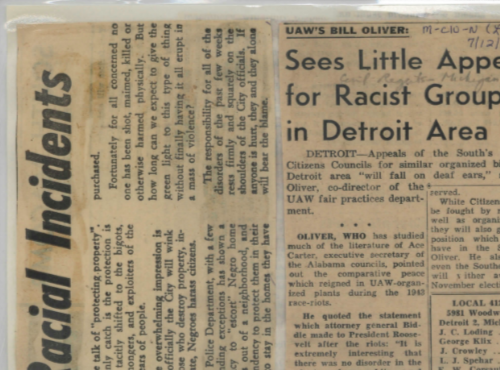

These clippings detail a late 1950s civil rights rally, a discussion of a Republican led attack on public housing, an article on “reoccuring racial incidents,” and on white citizens councils in Detroit.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

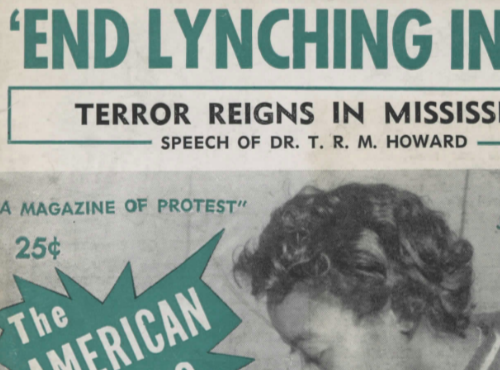

The January 1956 edition of The American Negro magazine, which was published in Chicago and distributed around the country. It had major audiences in Detroit and reported on northern and southern issues. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

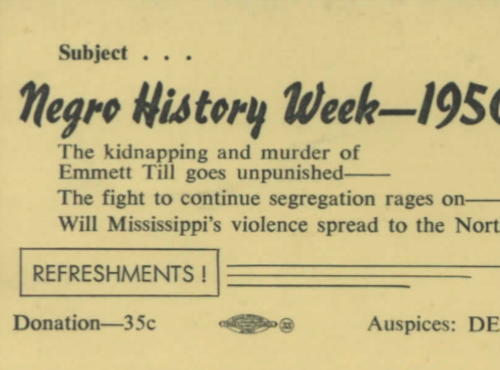

Popular education is an important part of organizing for civil rights. This flyer for a Negro History Week program in 1956 by the Detroit Labor Forum is one of many forums in Detroit that hosted educational events to update the community on ongoing events in a contextualized manner.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The Ku Klux Klan became particuarly active during World War II. This flyer describes not only the charged activism against hate groups but also the major support Franklin D. Roosevelt received from civil rights organizations. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Black Detroiters readily kept abreast of happenings in the Jim Crow South. One of the major occurances was white attacks on Black southerners, something Black Detroiters were aware of and challenged, as this November 1955 pamphlet from the NAACP explains.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

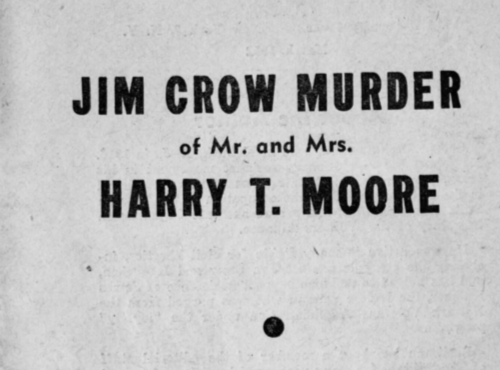

A pamphlet titled “The Jim Crow Murder of Mr. and Mrs. Harry T. Moore,” by George Breitman and published by Pioneer Publishers in March 1952. This pamplhet is based on the text of a speech made at a meeting of the Socialists Workers Party in January 1952.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

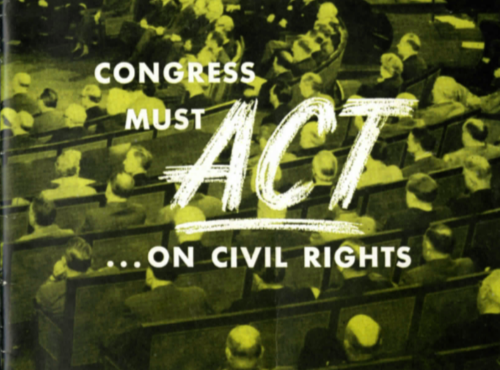

This pamphlet, published on December in 1955 by the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, urges Congress to “act on civil rights.” Organizations in Detroit are represented in it.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

This letter, published in a booklet for The Committee to Communicate Truth to Mississippi, is a series of statements written by prominent Detroit and national leaders to the “white people” of Mississippi, denouncing their racism. Many notable individuals from Detroit, like Ernest C. Dillard, wrote one.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

This 1955 NAACP pamphlet titled “It Can Be Done!” explicates the plausbility of equal rights and an end to school segregation, something as prominent in Detroit as it was in the South. Despite the 1960s heralded as the decade for civil rights, the 1950s built the foundation for the upcoming decade. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A 1950 article from The Truth covering the story of Thomas Coleman, a Black trade unionist who was an active union organizer and accused by the city of being a communist. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Oral history interview with Ernest Goodman, Richard Marks, and others, conducted by Elaine Latzman Moon in 1990. The group interview covers issues of civil rights in Detroit in the early 20th Century. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University