Housing

One way urban renewal transformed Detroit was the new housing patterns it created. On one hand urban renewal destroyed so much low-income housing without creating new low-income housing that the city had a vacancy rate of only 1 percent in the 1960s. On the other hand, the same expressway construction that destroyed black neighborhoods also cleared the way for whites to leave the city, move to suburbs, and open up housing for blacks able to purchase homes in neighborhoods from which they were previously excluded. Consequently, the 1960s marked a period of racially segregated expansion for black Detroiters into new neighborhoods and intense overcrowding. In response to continued housing segregation, discrimination, and poor housing conditions, black Detroiters engaged in multiple forms of housing activism, often determined by whether they rented or owned.

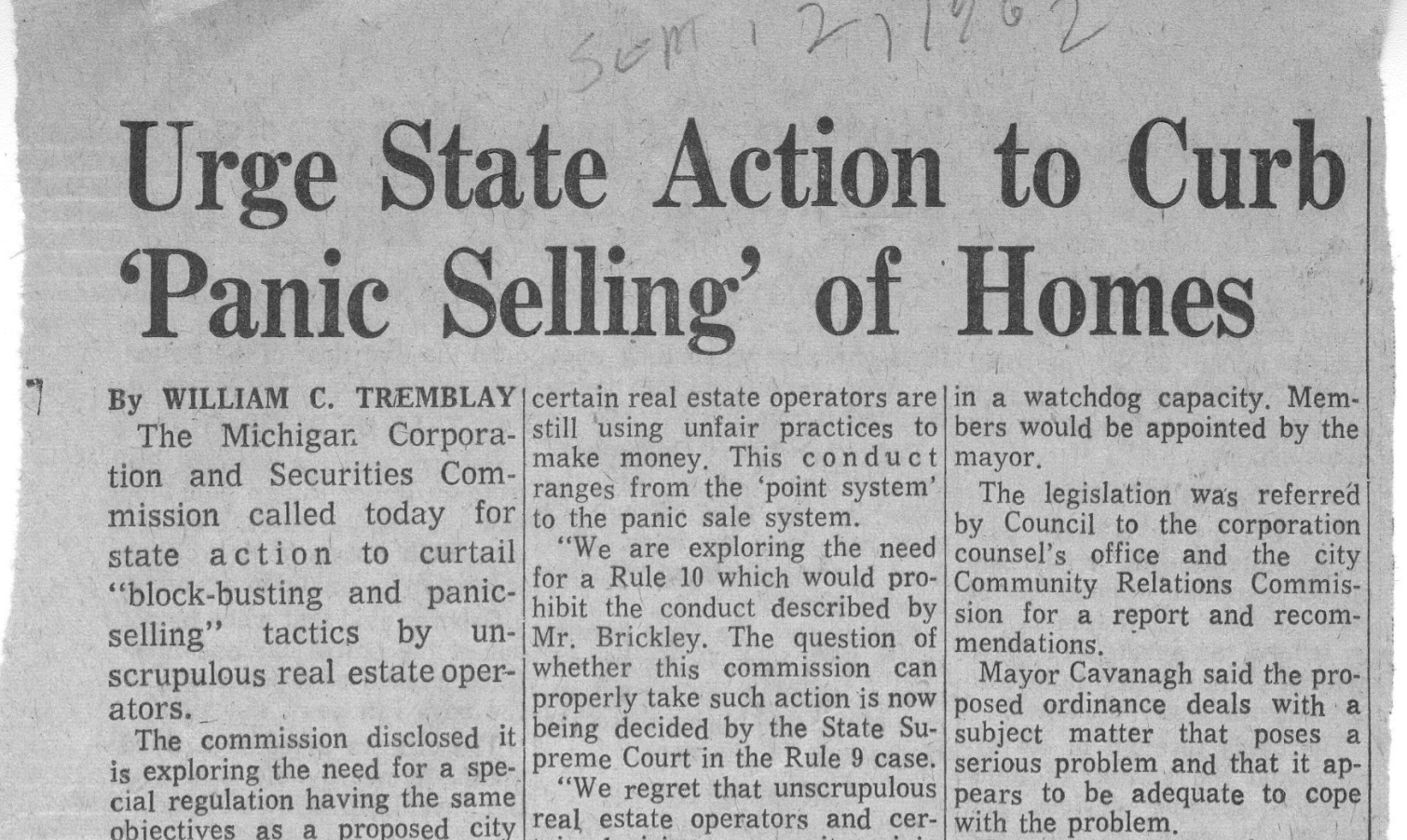

Home ownership for middle-class blacks in these newly open neighborhoods was often facilitated through a real estate practice called “blockbusting.” Knowing that most white residents would not live with black neighbors, real estate agents often sold a home to a black family then spread rumors to white residents that more black families were coming. By purchasing homes from white residents who refused to have black neighbors, real estate agents opened up homes in white neighborhoods to black families one by one, one block at a time. Blockbusting resulted in the transformation of all white neighborhoods into all black neighborhoods in only a matter of months.

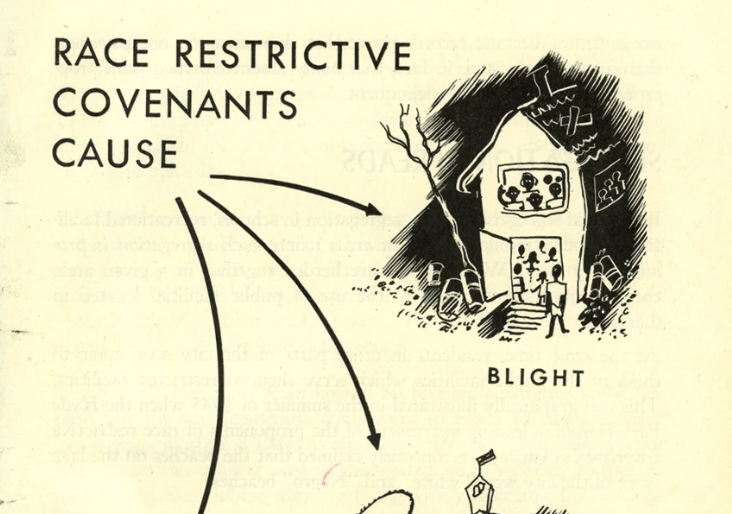

When real estate agents ran out of black professionals, they sold homes to working class blacks whose income often fluctuated with changes in the economy. When these families had difficulty paying the mortgage, it was common to take in boarders or double up with other families. Sometimes unable to make mortgage payments and maintain their already aging homes in difficult economic times, these families often sold their homes, creating high turnover in the neighborhood and resulting in lower overall property values. Wanting to live in neighborhoods where the value of their home would be easier to maintain, many professional blacks tried to move to suburbs. Yet, they quickly found themselves unable to do so because restrictive covenants and other forms of racial discrimination kept blacks out of suburban town and neighborhoods.

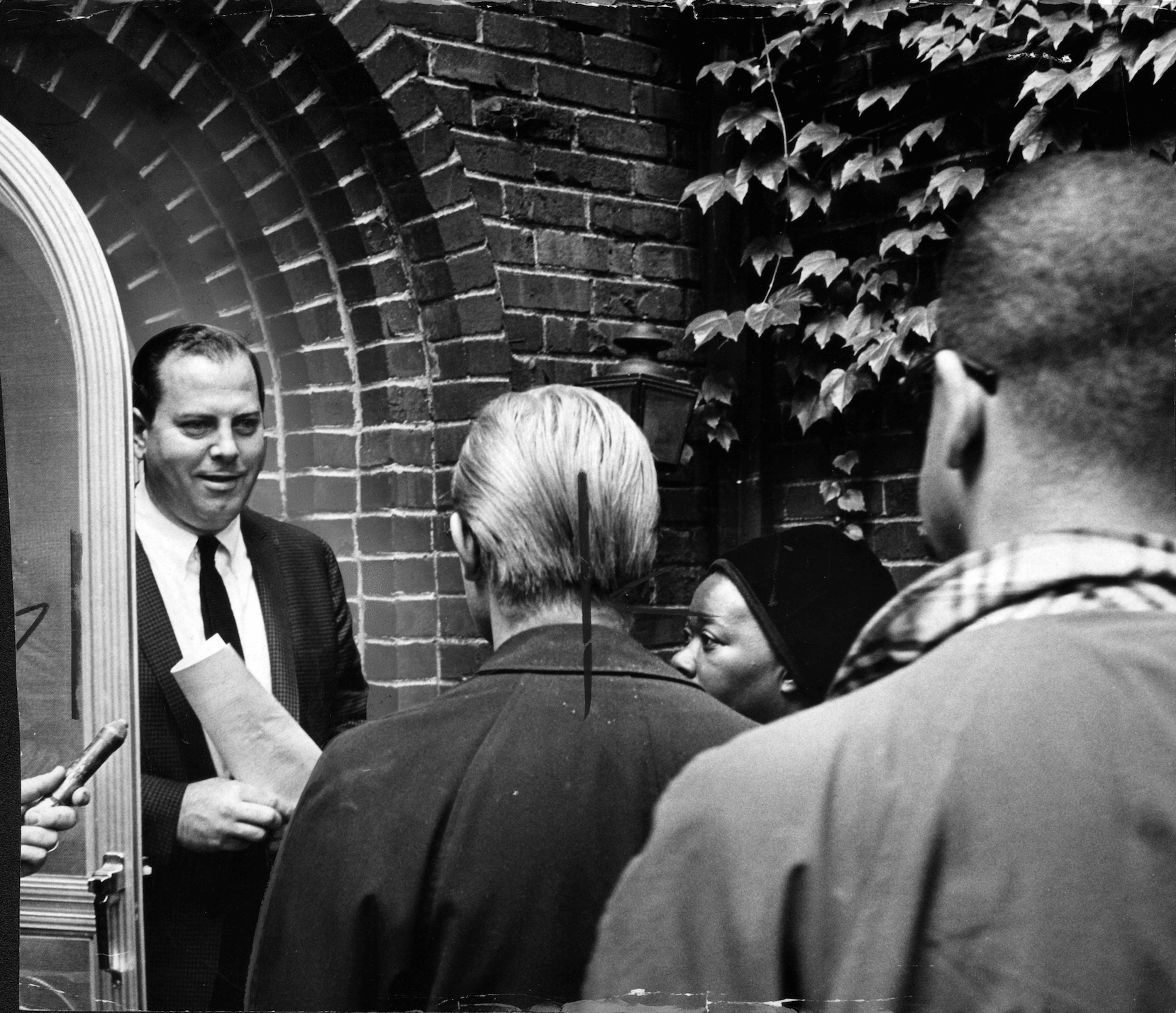

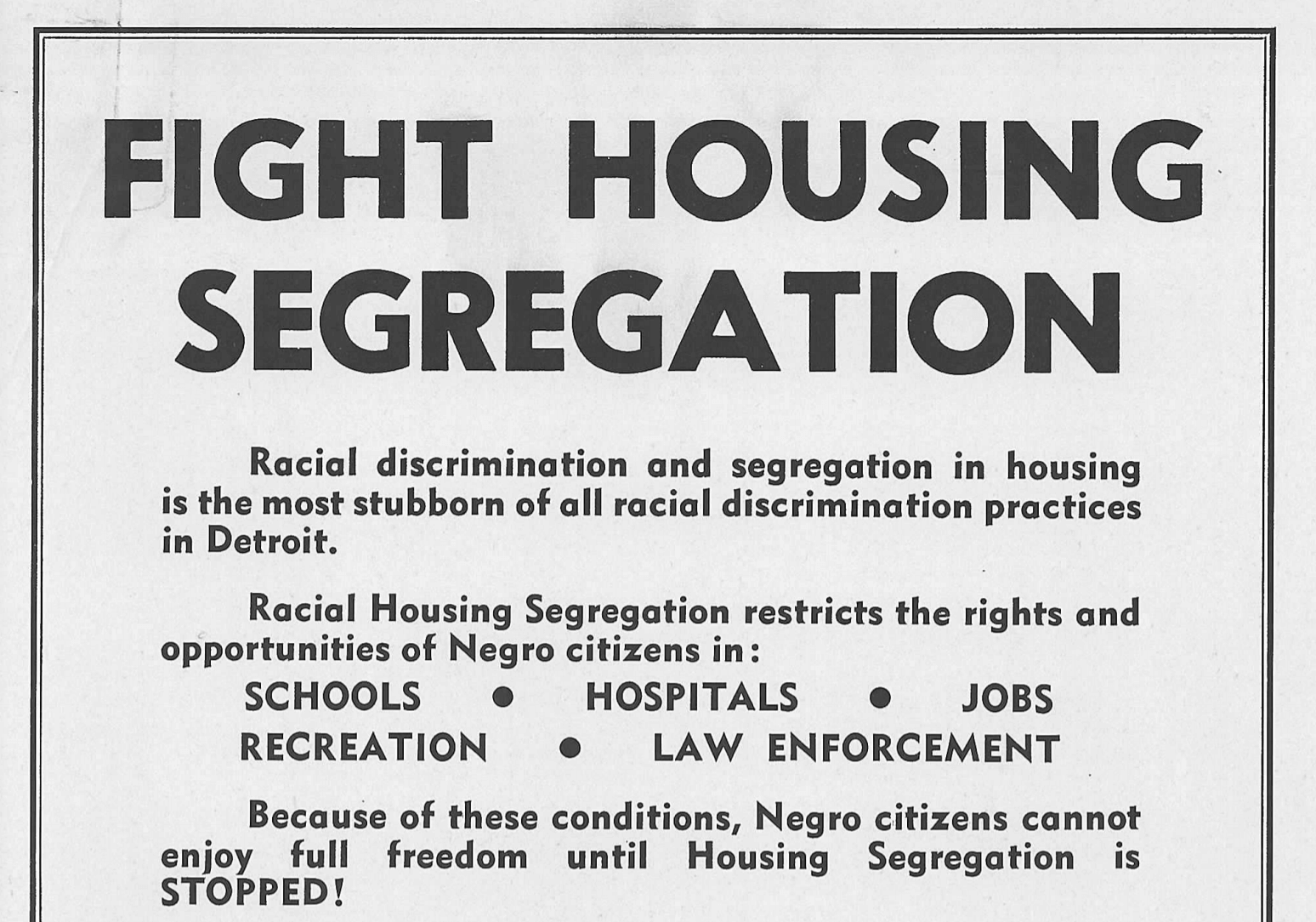

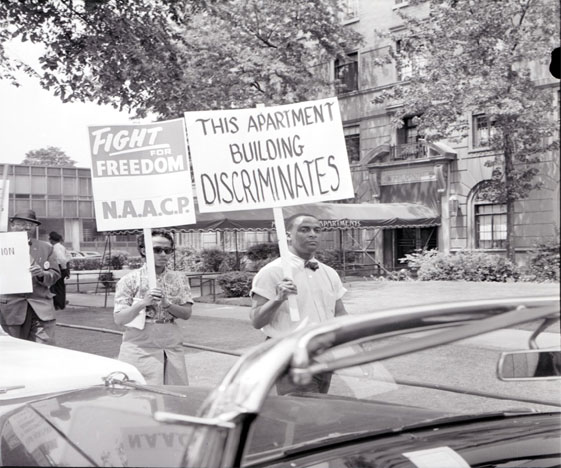

To eliminate this discrimination in home ownership, the NAACP and the Coordinating Council on Human Relations (CCHR) mounted a campaign for open housing in Detroit and its suburbs. By 1959, these activists forced the Michigan State Legislature to consider bills for fair housing and worked to expose the racist practices of suburban governments and real estate agents. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the NAACP organized demonstrations, open housing marches, and sent members to visit real estate agents to see which realtors were steering black Detroiters away from white neighborhoods inside the city and its suburbs.

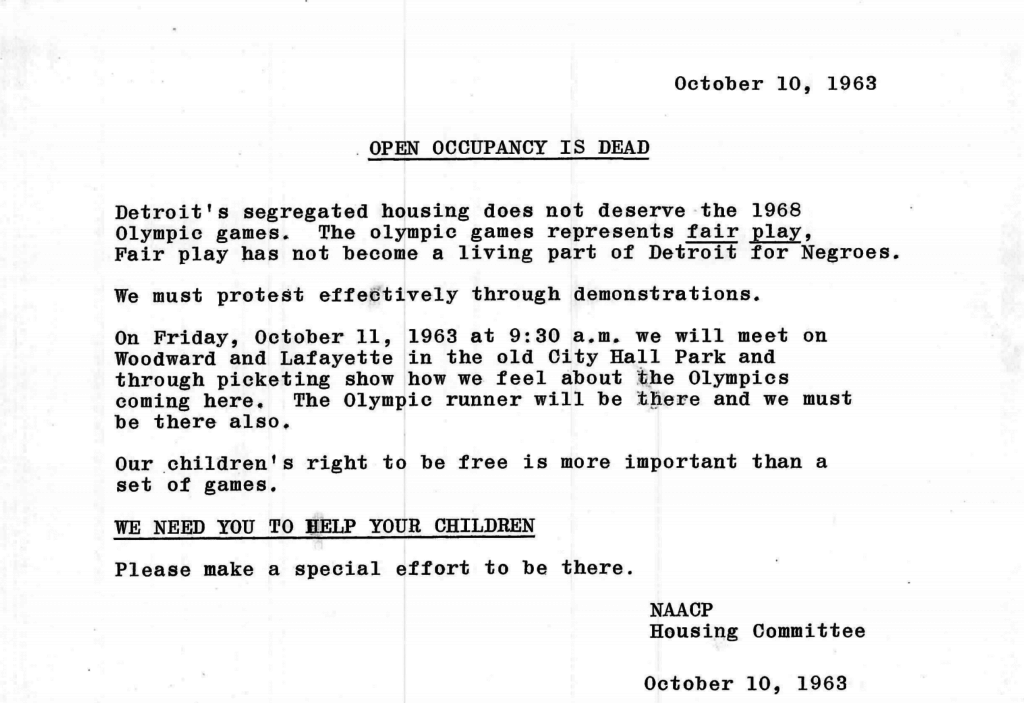

The most visible protest activity for open housing took place in 1963 during a ceremony that was part of Detroit’s bid to host the Olympics in 1968. The NAACP, CORE (Congress on Racial Equality), and the Trade Union Leadership Council protested the event with picket signs, seeing the event as an opportunity to embarrass the city into open housing laws on the world stage. These groups were upstaged by Uhuru, a group of young revolutionary nationalists, arguing that Detroit’s opposition to open housing made it undeserving of the Olympics. In contrast to the pickets of CORE and the NAACP, Uhuru booed the national anthem. When black track star Hayes Jones took the podium, Uhuru member General Baker took his picket sign, swung it at Jones and admonished him. “We’ve been running from the white man too long,” yelled Baker. In the wake of the demonstration several members of Uhuru were arrested for disturbing the peace.

While the results of this activity were mixed in Detroit’s suburbs, these protests did succeed in opening up exclusive neighborhoods like Boston-Edison and Arden Park to Detroit’s black elite and in opening up neighborhoods like Conant Gardens and Grixdale Park to other black professionals. However, these protests for open housing did little to improve the housing situation for Detroit’s poor blacks and blacks who rented. While the movement of whites to the suburbs created opportunities for black home ownership in new neighborhoods, for those who could not afford home ownership the housing crisis was extraordinary.

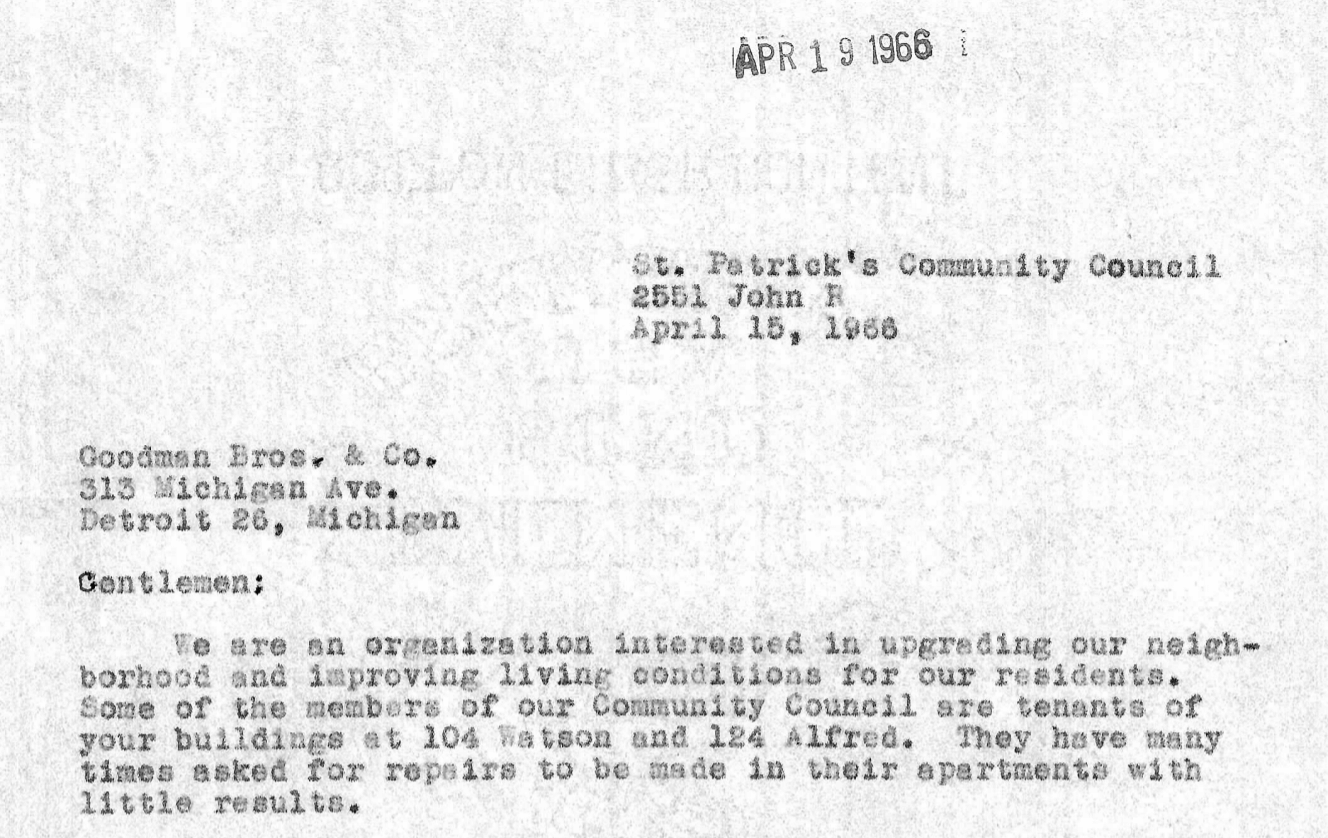

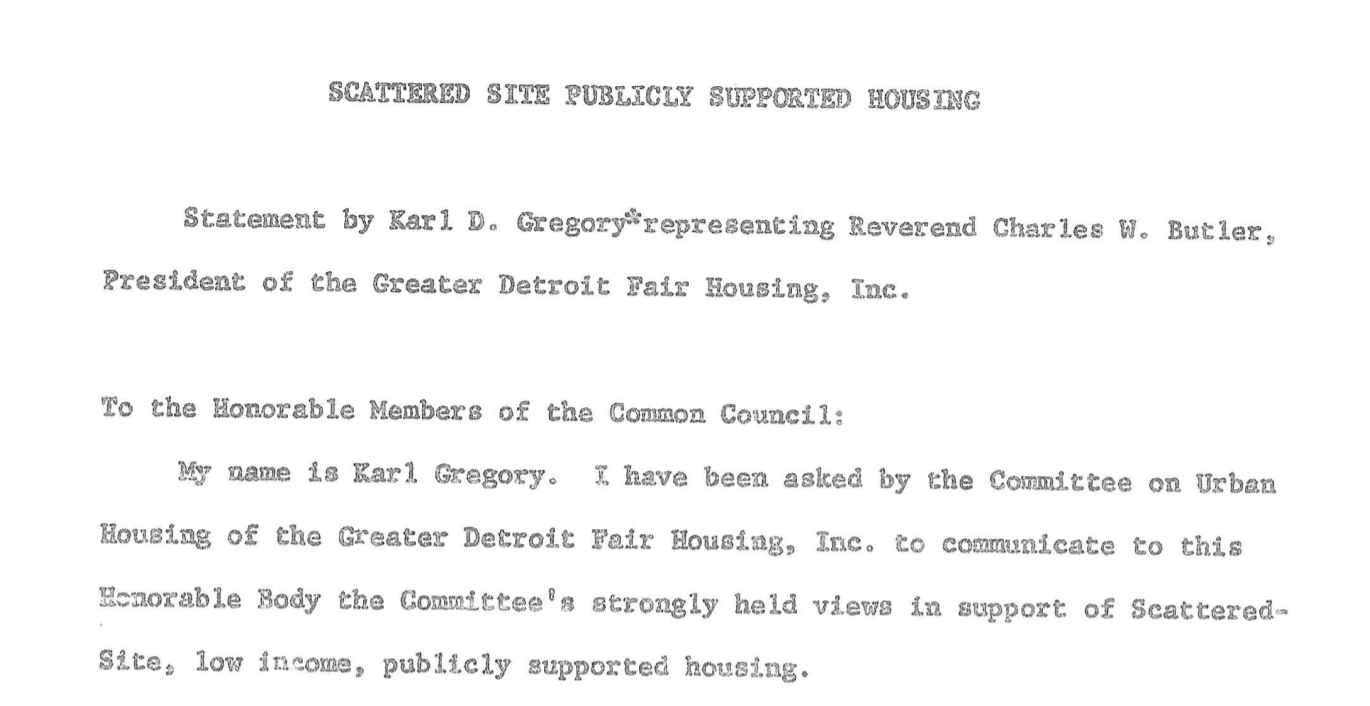

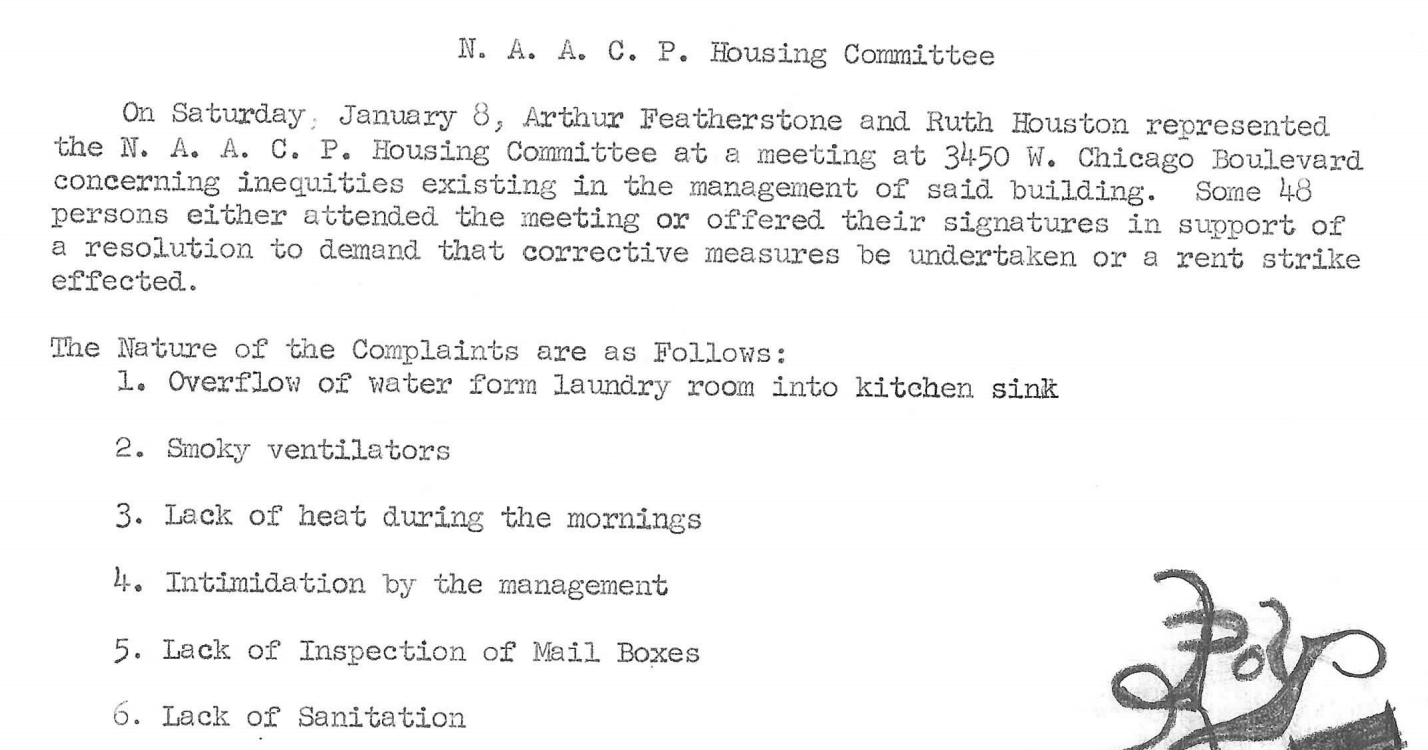

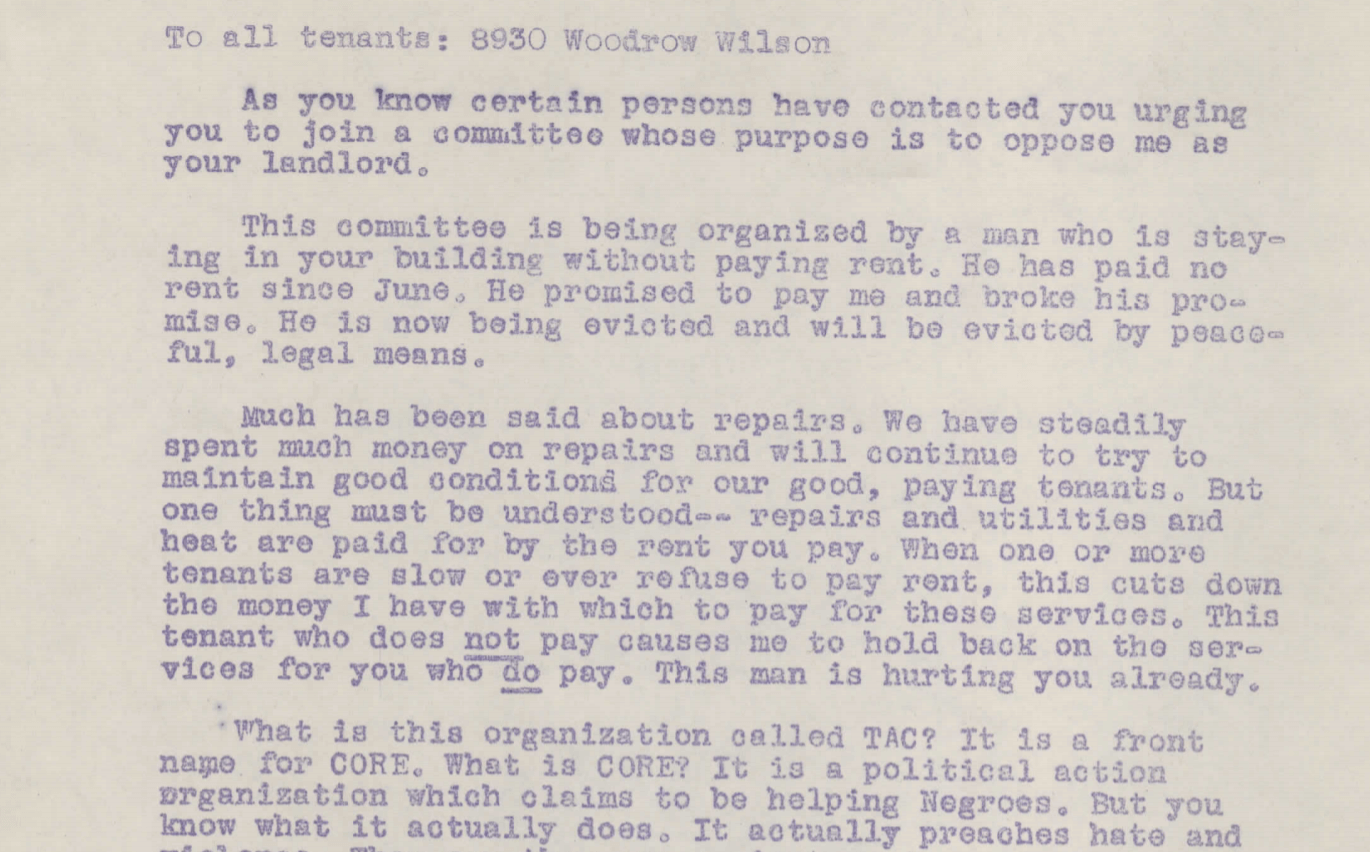

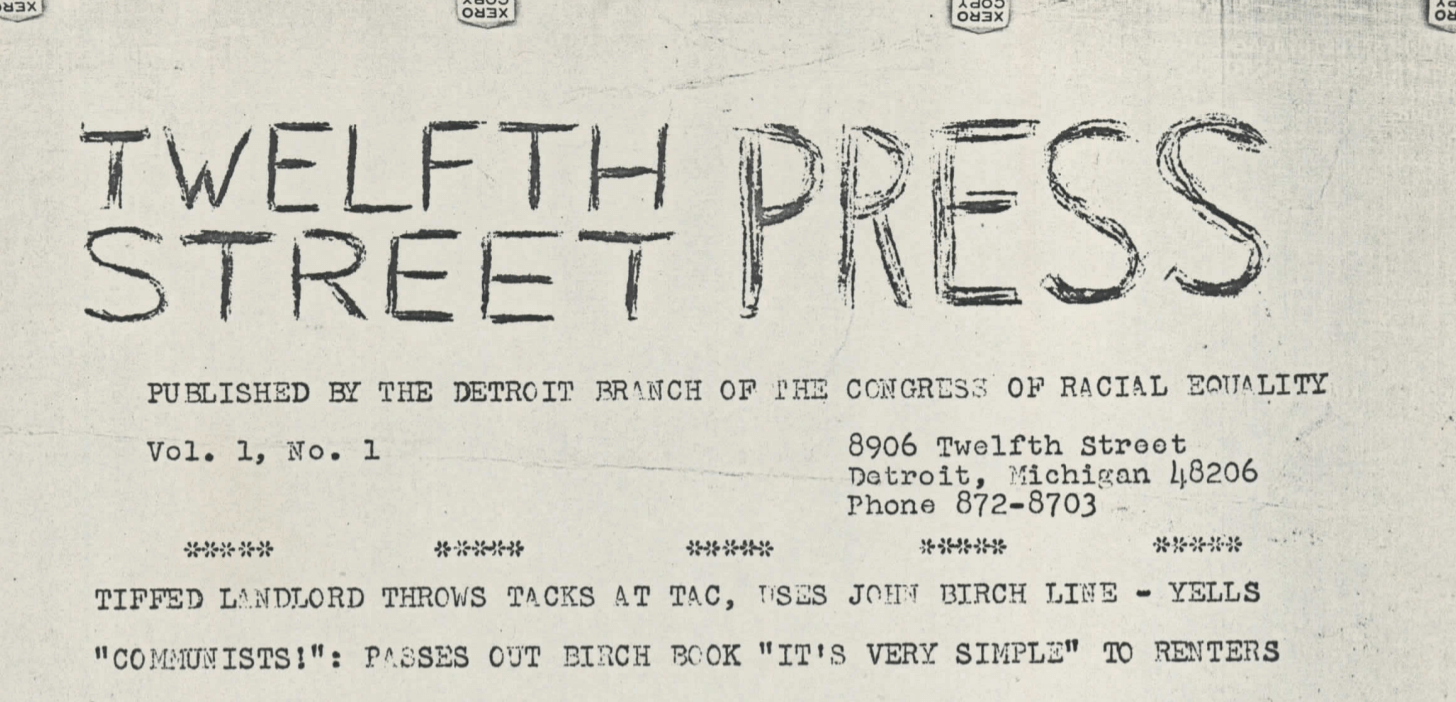

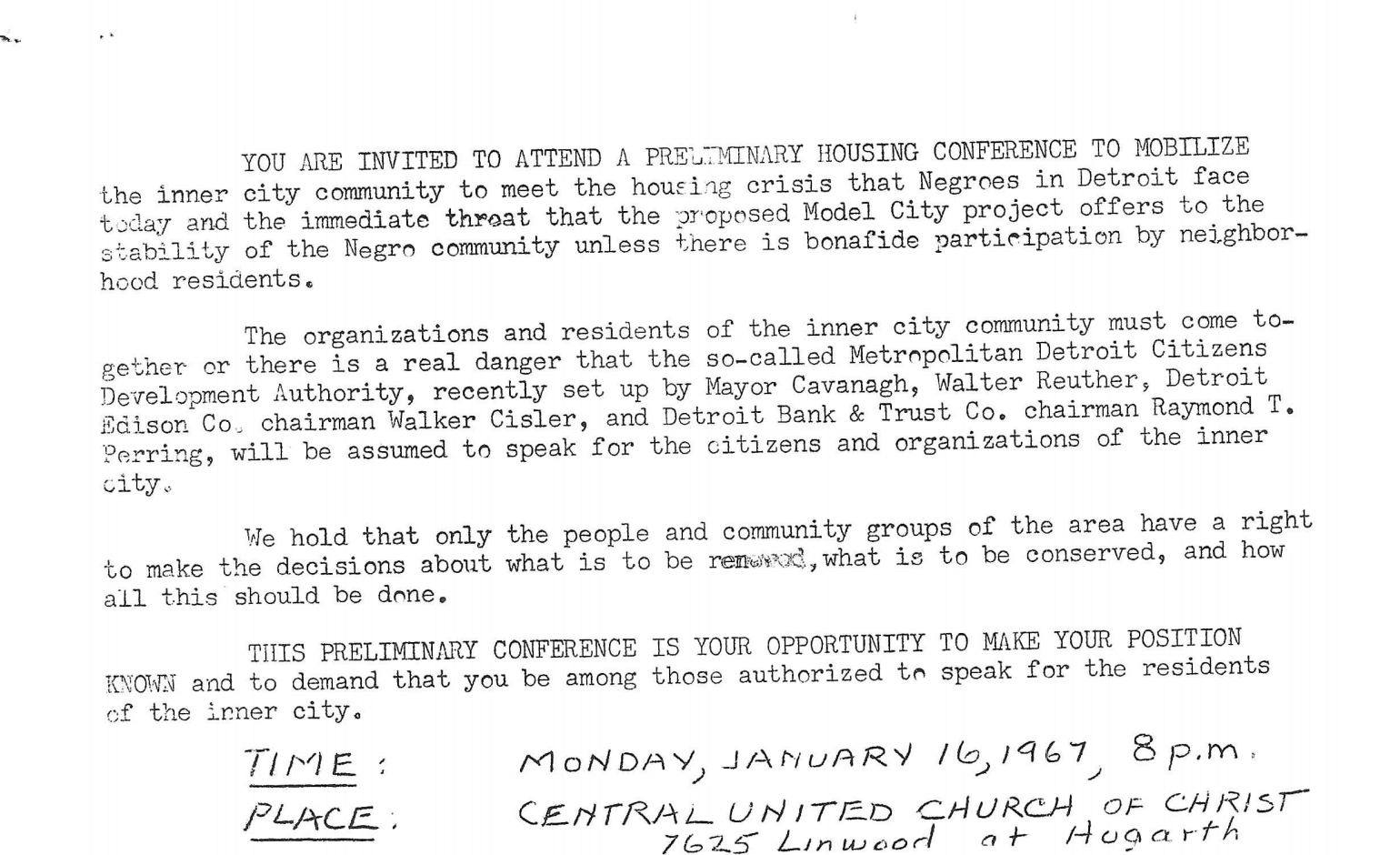

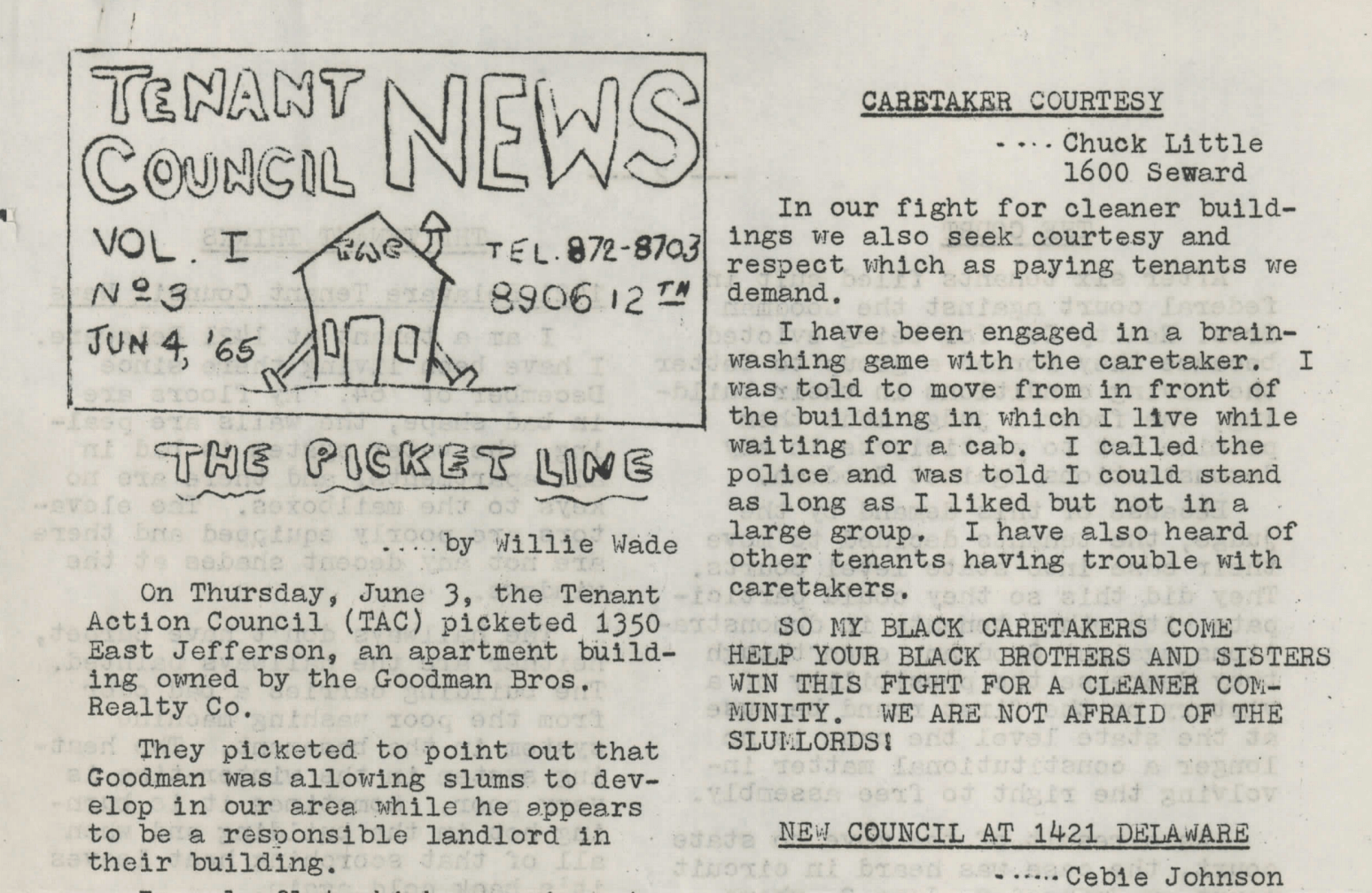

Understanding that the plight of the black poor was vastly different from those who might benefit from open housing, CORE and the NAACP also began to organize tenants’ rights campaigns. CORE created a community housing and planning review board made up of tenants in poor neighborhoods who protested in demand of affordable housing. By 1964, CORE and the NAACP had organized more than fifty tenants’ rights groups in apartment buildings on the West Side, empowering poor black Detroiters to solve their own problems with housing. That summer, they created an umbrella group called the Tenants’ Action Council (TAC) to coordinate the activities of these tenant led groups. With support from TAC, these groups organized rent strikes, picketed the suburban homes of absentee landlords and the construction sites of their other businesses, filed lawsuits against slumlords, and fought evictions.

Although these tenants’ rights groups won moderate reforms from the city including liens placed on properties where a landlord’s negligence endangered infants, overall conditions in apartment housing for poor black Detroiters changed very little and remained a source of tension up until the 1967 Detroit Rebellion and after.

References

David M.P. Freund, Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2010

David Goldberg, “Detroit’s Radical,” Jacobin, may 27, 2014

David Goldberg, “From Landless to Landlords: Black Power, Black Capitalism, and the Co-optation of Detroit’s Tenants’ Rights Movement, 1964-69,” The Business of Black Power, edited by Laura Warren Hill, Rochester, University of Rochester, 2012

Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1996

Clips from 2018 interviews with Detroit attorney Elliott Hall and former City Councilwoman JoAnn Watson, in which they explain how freeway construction and urban renewal programs have impacted the city of Detroit. — Videography: 248 Pencils

Some residents posted signs like this on their home to send a message to blockbusting realtors. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

NAACP Flyer, “Fight Housing Segregation,” 1962. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Members of the NAACP picket the apartment building at 4762 Second Street for discriminative housing practices. At right is Jackson (Jackie) Vaughn, III. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Tenant Council News, vol. 1, no. 3 (June 4, 1965). The Tenant Action Council picketed multiple properties to advocate for better living conditions. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives