Jobs and Unemployment

Although Detroit had been thought of as the place where factory workers could become middle class since Henry Ford began paying $5 a day in 1914, during the 1950s the size of Detroit’s factory workforce began to shrink dramatically. The city reached its population peak of just under 2 million in 1953 while the number of workers in manufacturing had already been on the decline for seven years. Hardest hit by this loss of jobs were black workers.

Beginning in 1953 technological and geographic changes in the auto industry began to decimate the city’s workforce and economy. Autoworkers had incredible power to stop factories from running and because they had gone on more strikes in the early 1950s than at any prior time, corporations began to relocate factories and introduce computers to them so that workers had less power. At Ford’s River Rouge plant, the largest employer of black people in the Detroit area from the 1910s-1950s, automation resulted in the workforce shrinking from 85,000 in 1945, to 54,000 in 1954, to only 30,000 in 1960. Between 1951 and 1953 Ford eliminated 4,185 jobs with automation. Automation enabled Ford to produce 154 engine blocks in one hour with only 41 workers compared to the 117 workers they needed before automation. The power of workers was also decreased by factory relocations. So many factories were relocated from Detroit during the 1950s that by 1960 the percentage of all automotive industry employment located in Michigan had fallen to 40 percent from 56 percent just ten years prior.

While all workers were negatively impacted by these changes black workers were hit the hardest. In 1960, the total percentage of white people out of work across Detroit was 5.8 percent while the percentage of black people out of work was 15.9. In the auto industry alone, 5.8 percent of whites were out of work compared to 19.7 percent of blacks. Because white workers’ racism resulted in the exclusion of black people from auto work until the 1940s, black workers had less seniority than whites and were therefore victimized by technological and geographically related layoffs more than whites. Since automation worked to eliminate massive numbers of entry-level jobs, massive numbers of young black people were prevented from getting that first job, like their fathers had, which provided them with valuable experience to secure better jobs down the road. Consequently, automation and decentralization worked to simply make it impossible for a large number of black young people to get jobs.

This situation changed temporarily in 1963 when the Vietnam War spurred demand for Chrysler products. Because Chrysler could not afford to automate and decentralize as Ford and General Motors had, its plants were still primarily located in Detroit and still utilized old technology. By 1963 it was the largest employer in Detroit and hired a massive number of black workers in 1963. Using old technology and trying to keep up with the automation enabled increase of production at Ford and General Motors, newly hired black workers at Chrysler found themselves the victims of what they called “niggermation.” Without relying on automation to keep up with the profits of Ford and General Motors, Chrysler forced its workers, most of whom were black, to produce as quickly as the automated factories of their competitors. Not coincidentally, this wave of black workers hired in 1963 became the base of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers after the 1967 Detroit Rebellion.

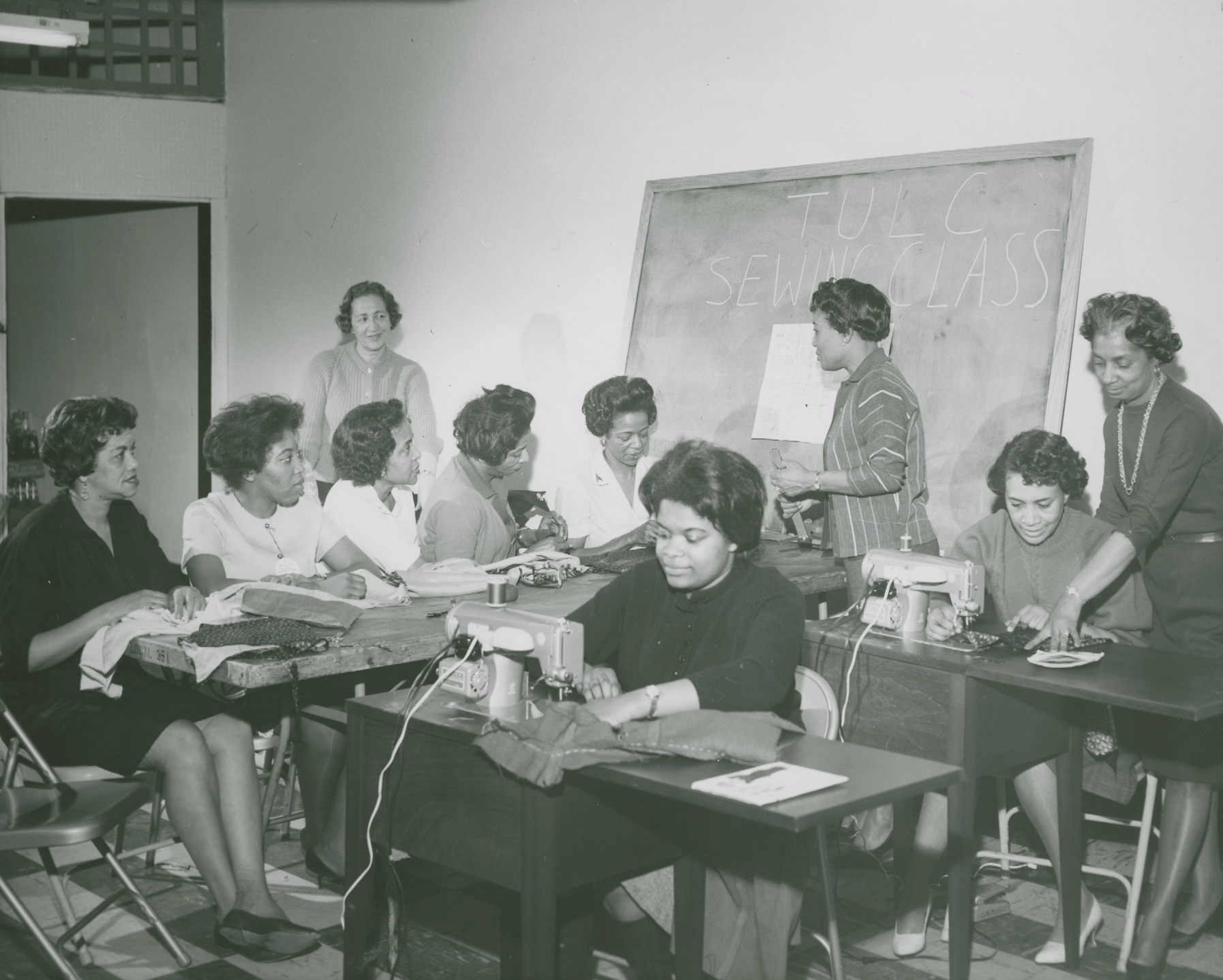

Outside the auto industry, especially in the construction trades, black workers also encountered tremendous discrimination. In 1963, the Trades Union Leadership Council (TULC), led by Horace Sheffield and founded in 1957 to address the particular needs of black workers, filed a complaint with the federal government and the Michigan Civil Rights Commission (MCRC) that local 58 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers was practicing racial discrimination in its federally funded apprenticeship program. Although the MCRC had no legal authority to take action, the federal government issued an injunction against the local resulting in the suspension of the program.

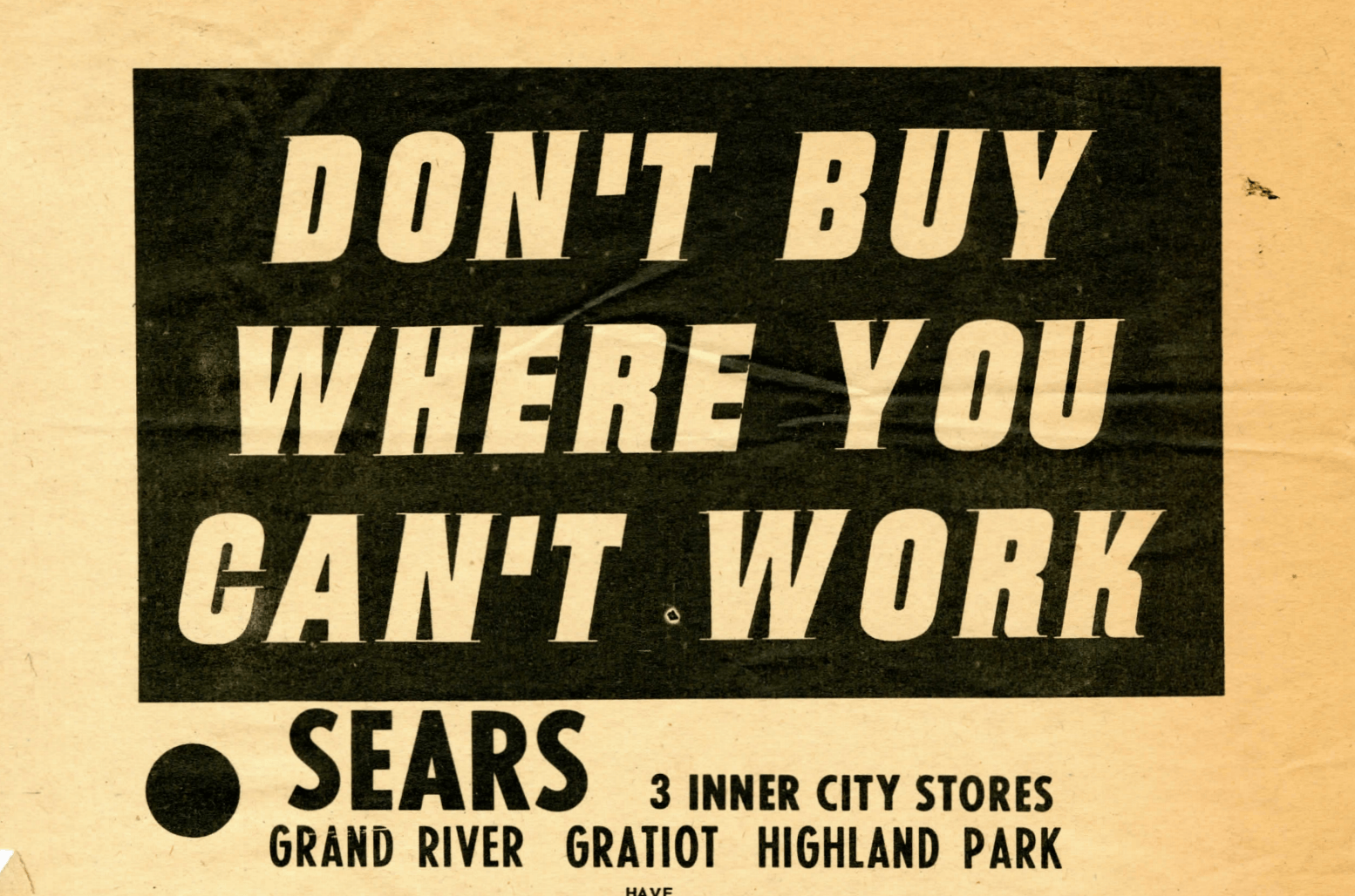

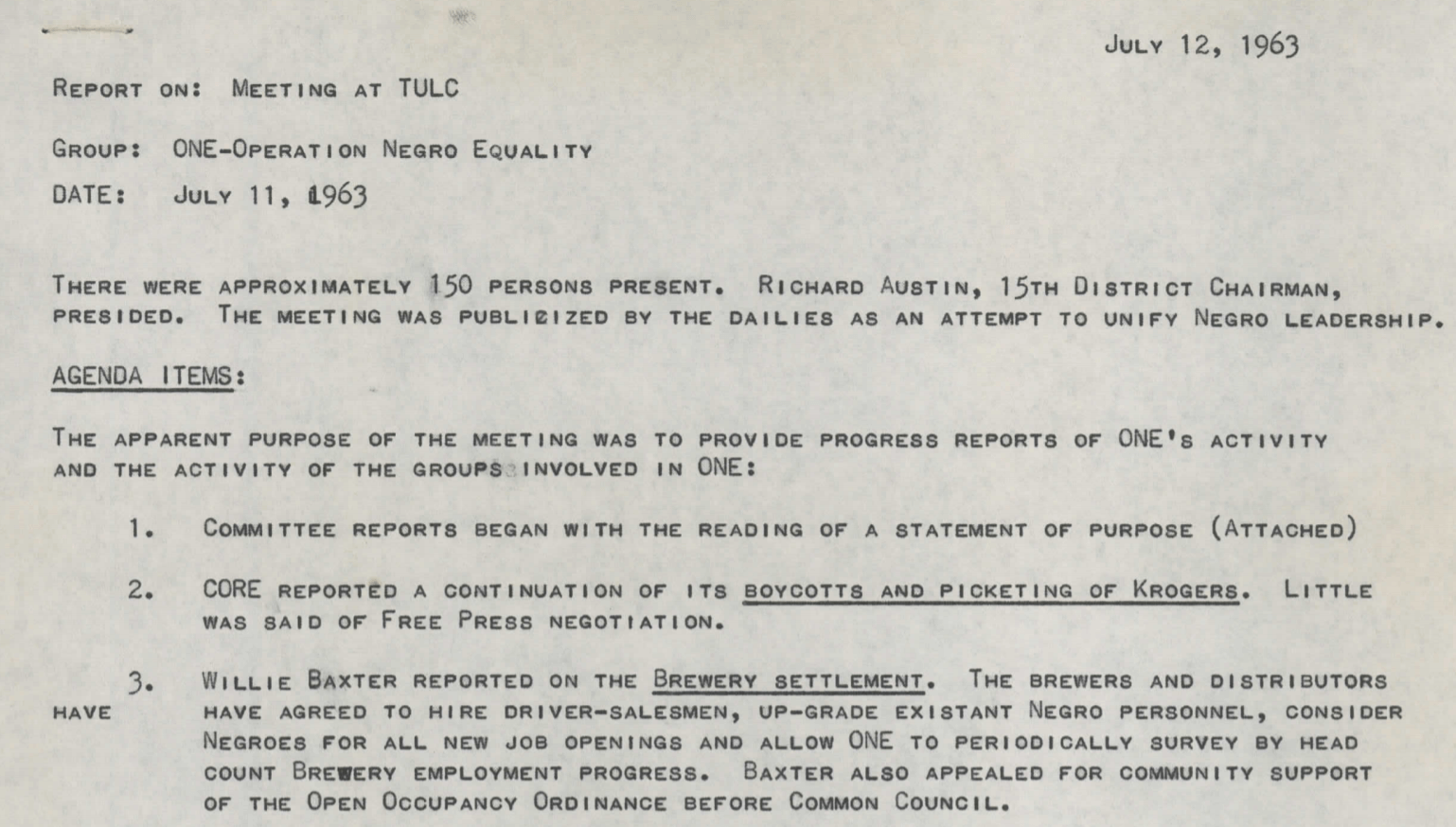

TULC understood the apprenticeship program discrimination as a symptom of much larger pattern of racial discrimination faced by black workers in construction and in the building trades. In an attempt to combat this larger pattern, they formed, along with GOAL, Uhuru, SNCC, CORE, the NAACP, and the Detroit Council on Human Rights, an umbrella organization called Operation Negro Equality (ONE). By threatening to picket construction job sites if both employers and unions did not commit themselves to immediate equality, ONE forced Mayor Cavanagh to intervene and negotiate between the TULC and the Detroit Building Trades Council. Cavanagh’s intervention lifted the injunction on the IBEW apprenticeship program and required employers to pledge to create racial equality in hiring.

Despite the Mayor’s intervention, apprenticeships were still hard to come by for blacks. Continuing their commitment to black trades workers, TULC began its own training program in 1966. While they succeeded in recruiting black workers to take union administered tests for various trades, very few blacks passed the initial screening and even fewer were able to survive the low paying three-to-five-year period of training required of the trades. By the time of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, it was clear to the leadership of TULC that creating black trades workers required a structural solution, in addition to increased training for black workers.

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, Boston, South End Press, 1998

David Goldberg, “Community Control of Construction, Independent Unionism, and the ‘Short Black Power Movement in Detroit,” Black Power at Work: Community Control, Affirmative Action, and the Construction Industry, Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2010

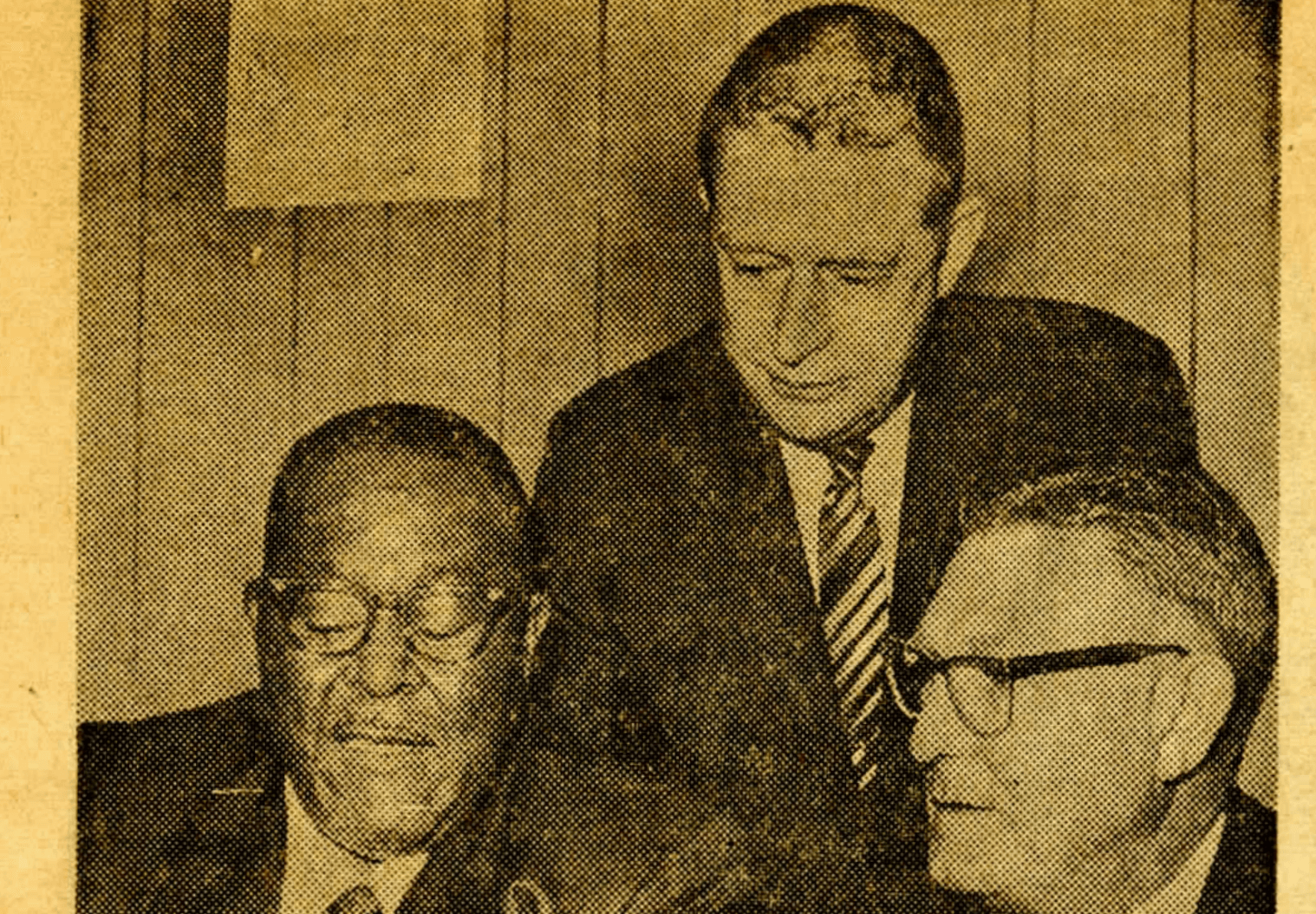

Detroit labor leaders Roy Reuther, Horace Sheffield, Walter Reuther, and Lillian Hatcher pose for a photo with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1957. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Clips from 2018 interviews with Charles Ezra Ferrell and Elliott Hall, in which they discuss the relationships between Black workers, organized labor, and the Civil Rights Movement in Detroit. — Videography: 248 Pencils

Clip from a 1988 interview with Detroit activist Ron Scott, in which he describes what life was like for Black workers at the Ford Rouge Plant in the 1950s-60s. — Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

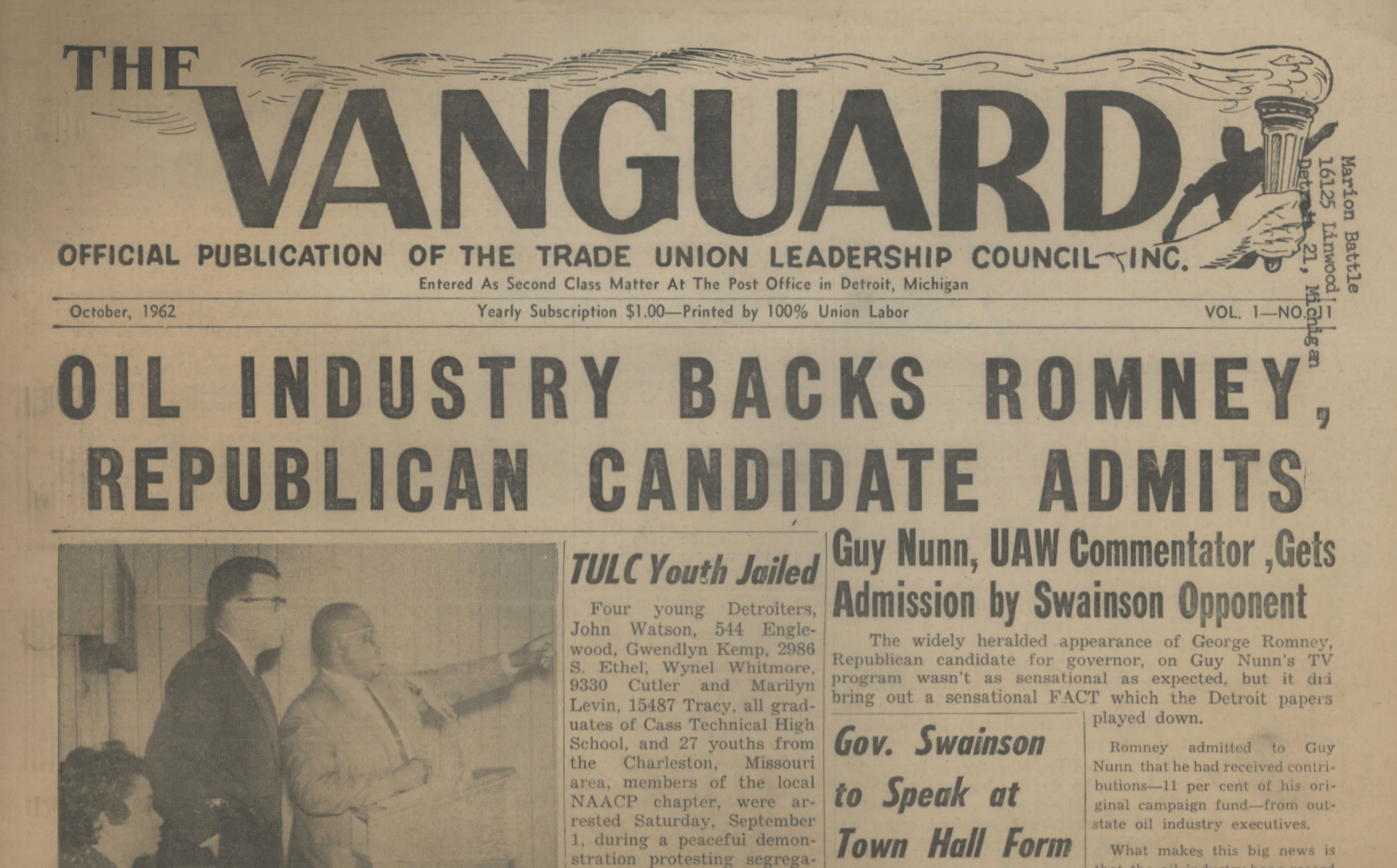

The Vanguard, vol. 1, no. 11, October 1962, official publication of the Trade Union Leadership Council. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Minutes of Operation Negro Equality (ONE)’s July 11, 1963 meeting. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A group of Black women participate in a TULC sewing class, one of many training programs organized by TULC to train Black workers in skilled trades. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives

Report “Employment and Income By Age, Sex, Color and Residence” in the Detroit Metropolitan area, prepared by the Detroit Commission on Community Relations, May 1963. — Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University