Part 3: New Directions in Black Politics

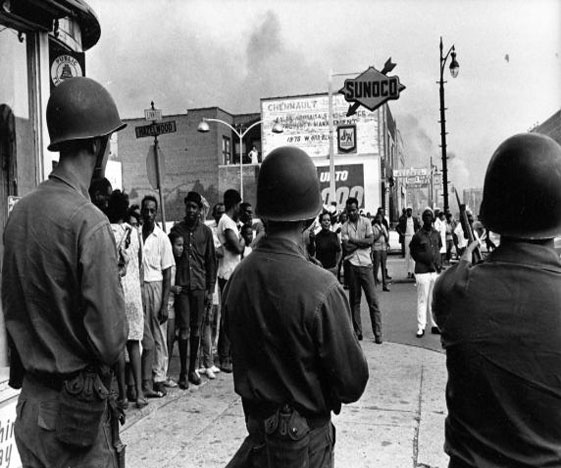

On the first Sunday following the 1967 Detroit Rebellion, Rev. Albert Cleage told his congregation that the rebellion had created an opportunity for black people. Cleage believed the time was right for black people to assume economic and social control over their communities–and political control of the city. He concluded his sermon by saying, “But this whole thing means that either the white folks downtown understand that the whole mood has changed; that we are going to be free. We are going to be free and that they have to do certain things, and if they realize that, that’s going to save a whole lot of trouble. If they don’t realize that, there’s going to be a whole lot more trouble.”

As Cleage and members of Central Congregation prayed to harness black Detroit’s power, the city’s leadership was trying to prevent more destruction. “I have got to talk to different leaders from now on,” Mayor Cavanagh declared, because the black civil rights leadership he relied on, “didn’t even know the people in the streets.”

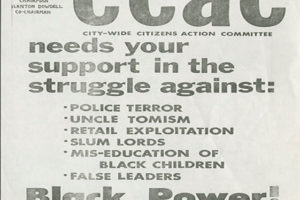

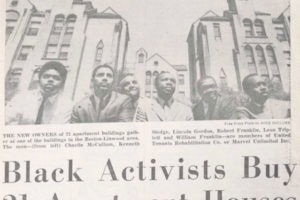

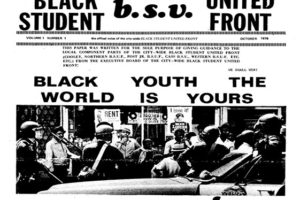

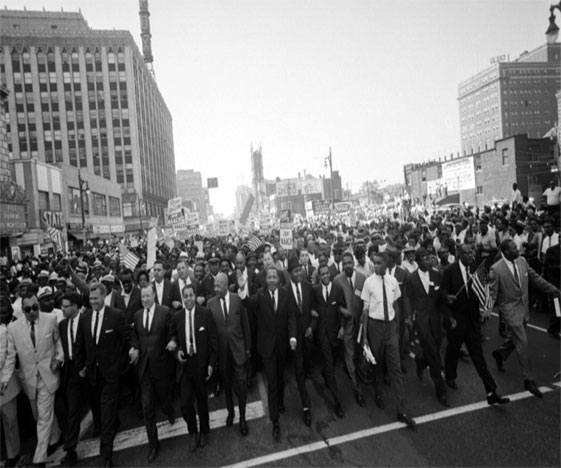

Sensing a shift in power relations between blacks and the city’s business and political class, Detroit’s Black Power leadership began experimenting with all kinds of strategies and tactics to take advantage of this shift and achieve political control over the city–culminating in the election of the city’s first black Mayor, Coleman A. Young, in 1974.

Learn about these strategies and tactics applied to various struggles for self-determination, economic justice, human rights, and political power during this era. What can the successes and shortcomings of these histories teach us about similar struggles being waged today?