Education

and the Black Student Movement

Following the 1967 Rebellion, Detroit’s public schools fell into increasing chaos. Excited about the possibility of participating in revolutionary guerilla warfare, so many black youth in Detroit were dropping out of school that fall to become guerilla fighters that Rev. Cleage used his Michigan Chronicle column to council black youth to stay in school. Although those who dropped out were a minority of students, the Rebellion still had an impact on all students, leading many to bring revolutionary energy with them to the classroom. Knudsen Jr. High on Detroit’s east side closed several times that Fall amidst a belief that a riot between black and white students was inevitable. Before the 1967 Rebellion, many black Detroiters had already believed that the school board was hopelessly racist. Feeling empowered after the Rebellion, black Detroiters increasingly began to see community control of schools as the way to resolve this chaos and provide students with a decent education.

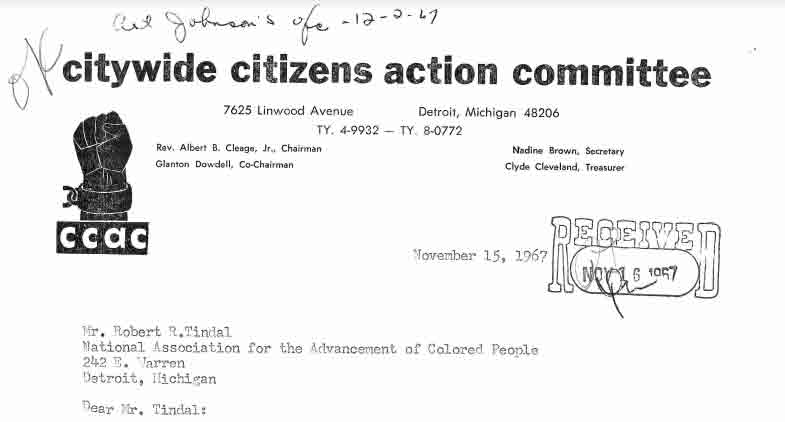

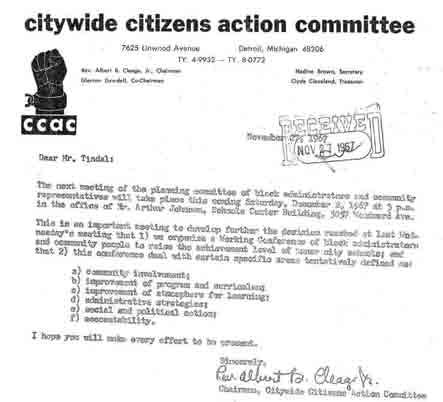

The movement for community control of schools in Detroit was made up of several organizations all sharing the same basic goal of transferring power to control schools over to Black Detroiters. The first to gain a following after the Rebellion was Citizens for Community Control of Schools (CCCS). CCCS organized rallies and developed relationships with activists from the Ocean Hill-Brownsville struggle for community control of schools in Brooklyn, NY and with activists from the community control of schools movement in Washington D.C. Highly influenced by successes in those two cities, CCCS believed that the solution to gaps in skills between black and white students, and to overly harsh punishments for black students, was to transfer decision making authority to numerous local community boards made up of students, parents, teachers, and other community members elected at a neighborhood level. CCCS’s plan for community control involved organizing these boards and securing for them the power to budget, hire, and set standards of accountability for all school administrators. CCCS launched an educational campaign around their program with assistance from the Michigan Chronicle and organized sit-ins, pickets, and other direct-action tactics. They also launched a magazine called Foresight, edited by Grace Lee Boggs, and were closely connected to the Black Teachers Workshop.

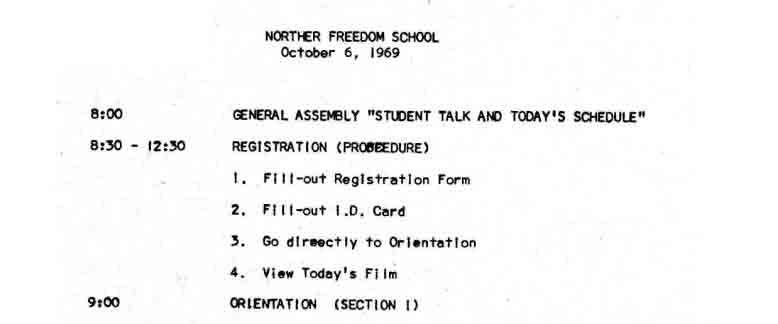

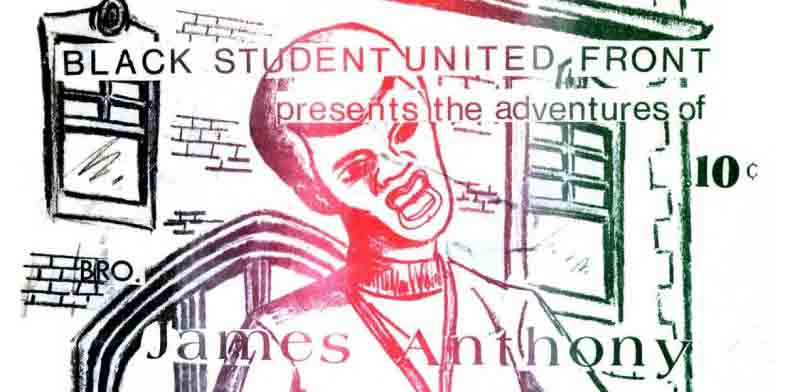

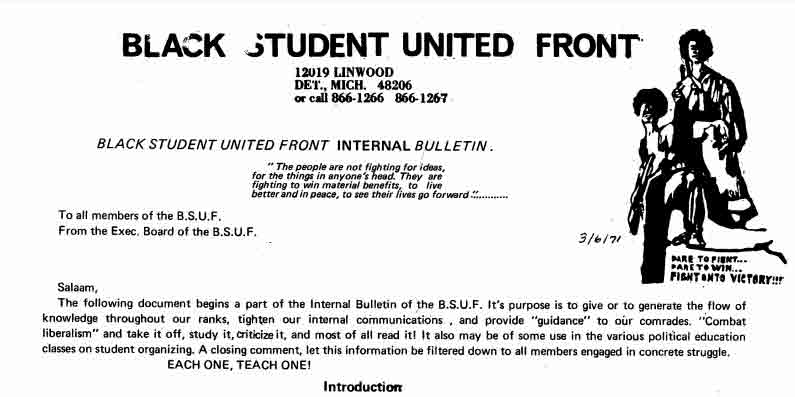

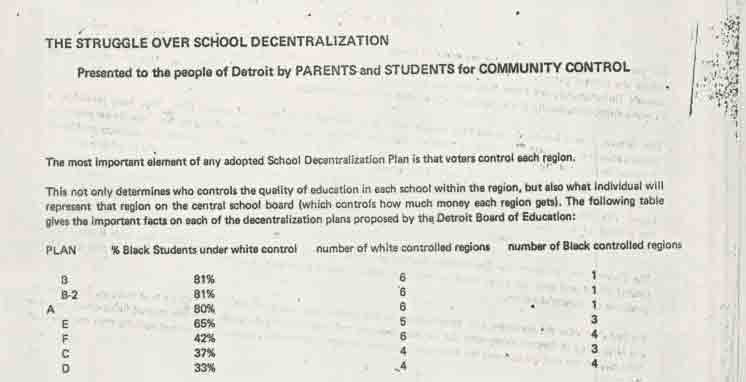

The West Central Organization (WCO) was another organization that was important to the local movement for community control of schools. In support of then Senator Coleman A. Young, who authored a bill for the for school decentralization in 1969, WCO undertook a study mapping out all the possible combinations of Detroit High School districts to figure out which would create the maximum measure of racial sympathy between students and school boards. To present this research WCO organized a five-day conference in 1969 that resulted in a plan for decentralizing the school district known as “the Black Plan,” as well as several recommendations regarding educational philosophy, racism in schools, curriculum, teachers’ rights and responsibilities and the rights of parents and students. The WCO conference also resulted in the creation of an umbrella group called Parents and Students for Community Control (PASCC), consisting of twenty organizations, including the WCO and the Black Student United Front (BSUF). PASCC held hundreds of rallies and meetings and made regular radio and television appearances. The BSUF organized in twenty-two schools, published a newspaper, wrote a comic book, and served as a youth wing for the League of Revolutionary Black Workers.

Another organization for community control of schools made up of students was Students for Justice, which over time evolved into the All-African Peoples Union (AAPU). Students for Justice was committed to direct-action to satisfy their demands for more black content in school curriculum, elimination of the district’s tracking system, and more black administrators for black schools. Students for Justice, working with unorganized parents in support of community control, led a walkout and boycott of two Detroit high schools over their demand for black administrators. In both cases the Detroit School Board yielded decision-making power over hiring principals to the student and parents groups.

Despite these victories, Students for Justice—and their advisor Dan Aldridge—saw that the community control of schools movement needed to better understand and develop a vision for the kind of education community control of schools they wanted. As Aldridge told a group of principals about the student led actions that resulted in students hiring new principals, “The disruptions did not keep the kids from continuing to lose their desire to learn. They were not interested in learning of any kind.” Despite the victories they produced, Aldridge believed, “Disruption tactics failed because no programs were developed to replace the disrupted programs.” Students for Justice therefore evolved into AAPU and began to focus on developing programs for schools and for the general direction of education.

AAPU developed a program called “Education to Govern,” which argued that community control of schools was only a partial solution to black students’ educational problems if it did not also entail a radically different vision of the purpose of education. Greatly influenced by James and Grace Lee Boggs, AAPU argued that because automation was quickly eliminating the need for black factory workers, the community control of schools movement needed to develop curriculum for black students that would give them the skills needed to transform the entire country, the economy, and themselves, rather than prepare them for work. To implement this program, AAPU as well as the Committee for Political Development began to attend meeting for community control of schools to organize people already involved in the movement around their “Education to Govern” program.

These groups all remained active in the movement for community control of schools until at least 1971, when the Detroit School District was decentralized into regions, each consisting of 25,000-50,000 students, and each having their own school board, from which one member would serve on a city-wide central school board.

References

Stanley J. Berkowitz, An Analysis of the relationship Between the Detroit Community Control of Schools Movement and the 1971 Decentralization of Detroit Public Schools, Wayne State University, Doctoral Dissertation, 1973

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Clip from a 2018 interview with veteran Detroit activist Helen Moore, in which she discusses educational activism in Detroit and her organization, Black Parents for Quality Education, in the late 1960s. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Pamphlet, Citizens for Community Control of Schools. The CCCS advocated for community control of schools. In order to promote a positive outcome for Black children, they recommended shifting power away from a centralized board to a local community board. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Parents and Students for Community Control presented \”The Black Plan\” for Black control of Black schools (1970). –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

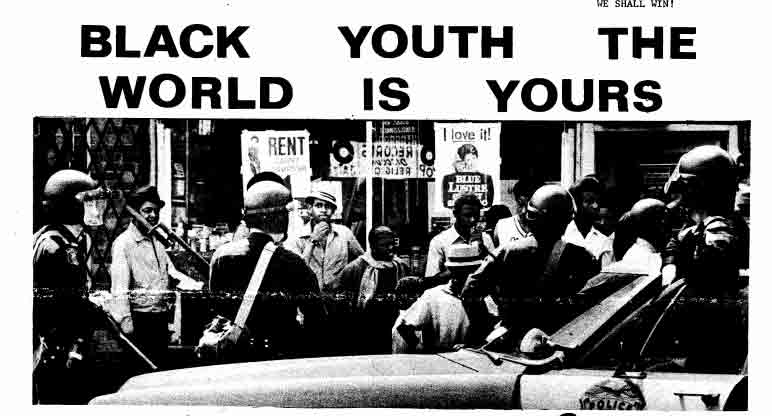

The first edition of Black Student Voice, the official newspaper of the city-wide Black Student United Front, published in October 1970. –Credit: Files of David Goldberg

Clip from a 2018 interview with veteran Detroit activist Dan Aldridge, in which he discusses the All African Peoples Union and educational activism in Detroit in the late 1960s. –Videography: 248 Pencils

\”Education to Govern,\” first published by the All-African Peoples Union in April 1971. The pamphlet includes articles from Dan Aldridge and Grace Lee Boggs, along with \”Education to Govern: A Program for Learning Now!\” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives

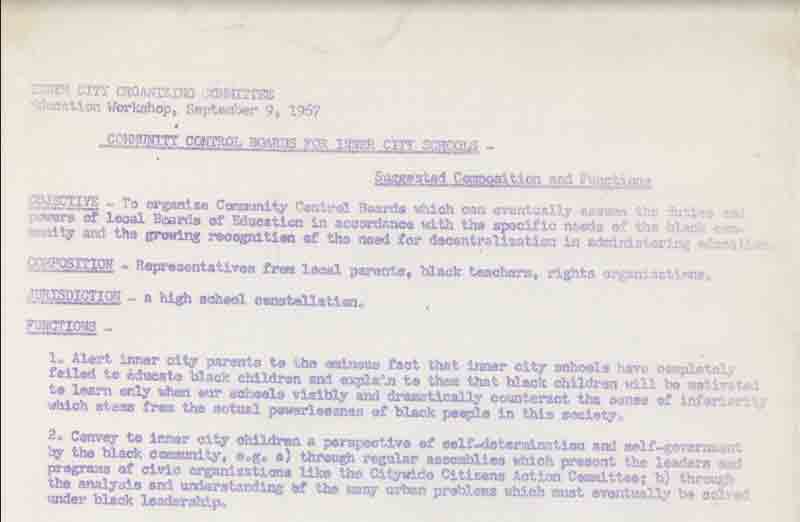

In their Education Workshop of September 9, 1967, the Inner City Organizing Committee suggested the creation of Community Control Boards. The objective of these boards was to assume the duties and powers of local Boards of Education in accordance with the specific needs of the Black community. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

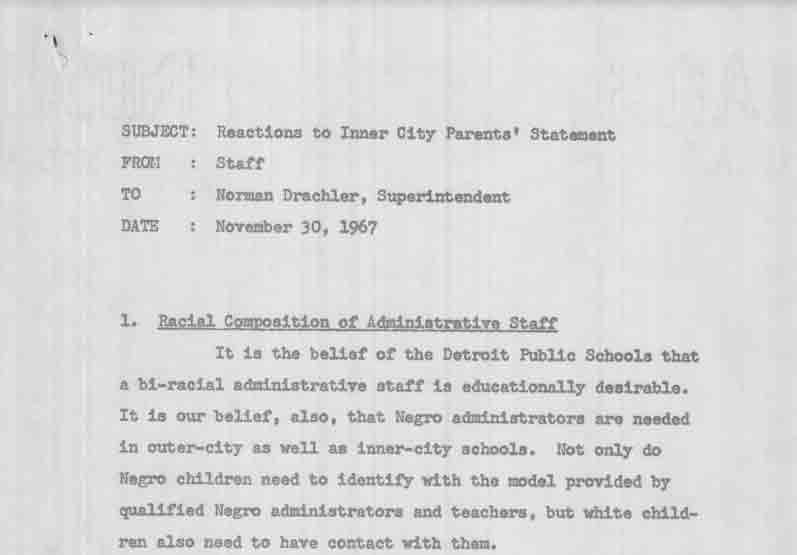

\”Reactions to Inner City Parents\’ Statement,\” memo to Detroit Public Schools Superintendent Norman Drachler, November 30, 1967. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Unmarked newsclipping, \”Serious Business\” by Dan Aldridge, on community control of schools.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.