Police Brutality and STRESS

In the minds of many black Detroiters, police brutality was worse after the Rebellion than it was before. Within two months of the Rebellion, black Detroiters increasingly began to believe that the police were taking revenge for the Rebellion out on everyday average black Detroiters. Newspapers widely reported that police were joining the Nationl Rifle Association (NRA) in droves and purchasing carbines in case another outbreak occurred. Newspapers also reported that the Detroit Police and Fireman’s Association for Public Safety was a sponsoring organization of several white self-defense rallies held in Northwest Detroit and in Detroit suburbs. By October 1967, these developments made many black Detroiters believe that the police were planning to place them in concentration camps.

A little more than a month after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Detroit police exploded on Detroiters who participated in the Poor People’s Campaign. In coordination with local organizers, the national movement came to Detroit in May of 1968 on its way to set up an encampment in Washington, D.C. While the Cavanagh administration welcomed the demonstration and march, the Detroit Police Department felt differently.

Gathering outside Cobo Hall for a permitted march and demonstration, marchers were charged at by Detroit police officers and beaten. Samuel J. Dennis, who was a field representative of the United States Department of Justice reported, “I saw police officers ride horses into a crowd which I judged to be under control. In addition, I saw officers strike individuals in that crowd with night sticks.” An additional observer from the justice department confirmed Dennis’s statements, “The actions of the horsemen on the crowd were, in my judgment, uncalled for. The crowd was just standing there observing, walking in and walking out. I observed no provocation on the part of marchers, marshals, or the crowd for officers to behave in that manner.” Because the police acted with no provocation, many black Detroiters believed that the police planned their attack on the demonstration in advance.

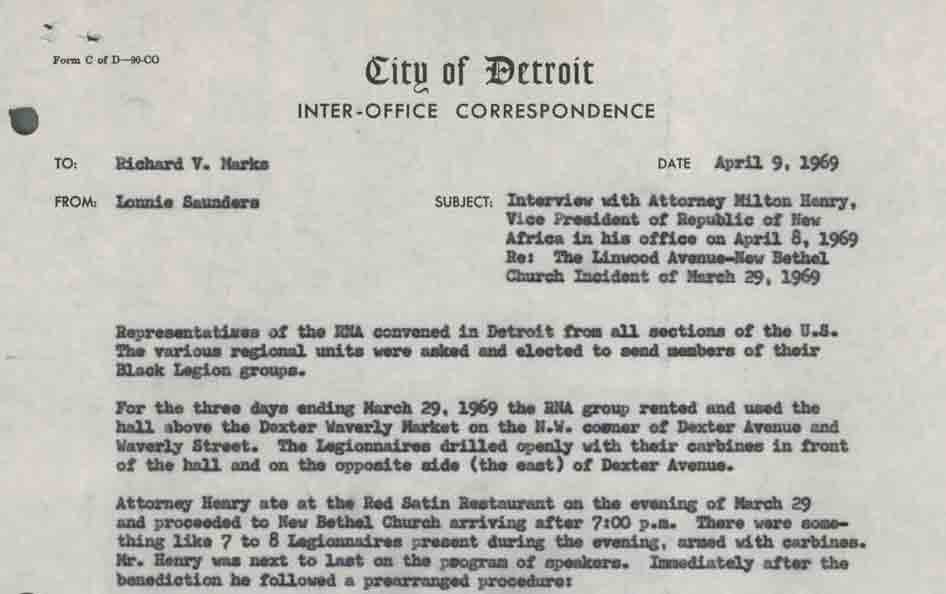

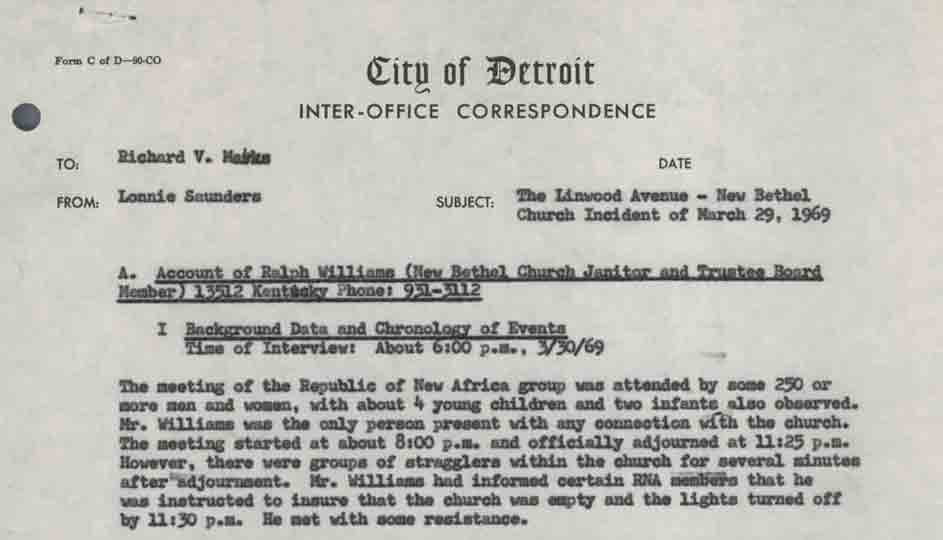

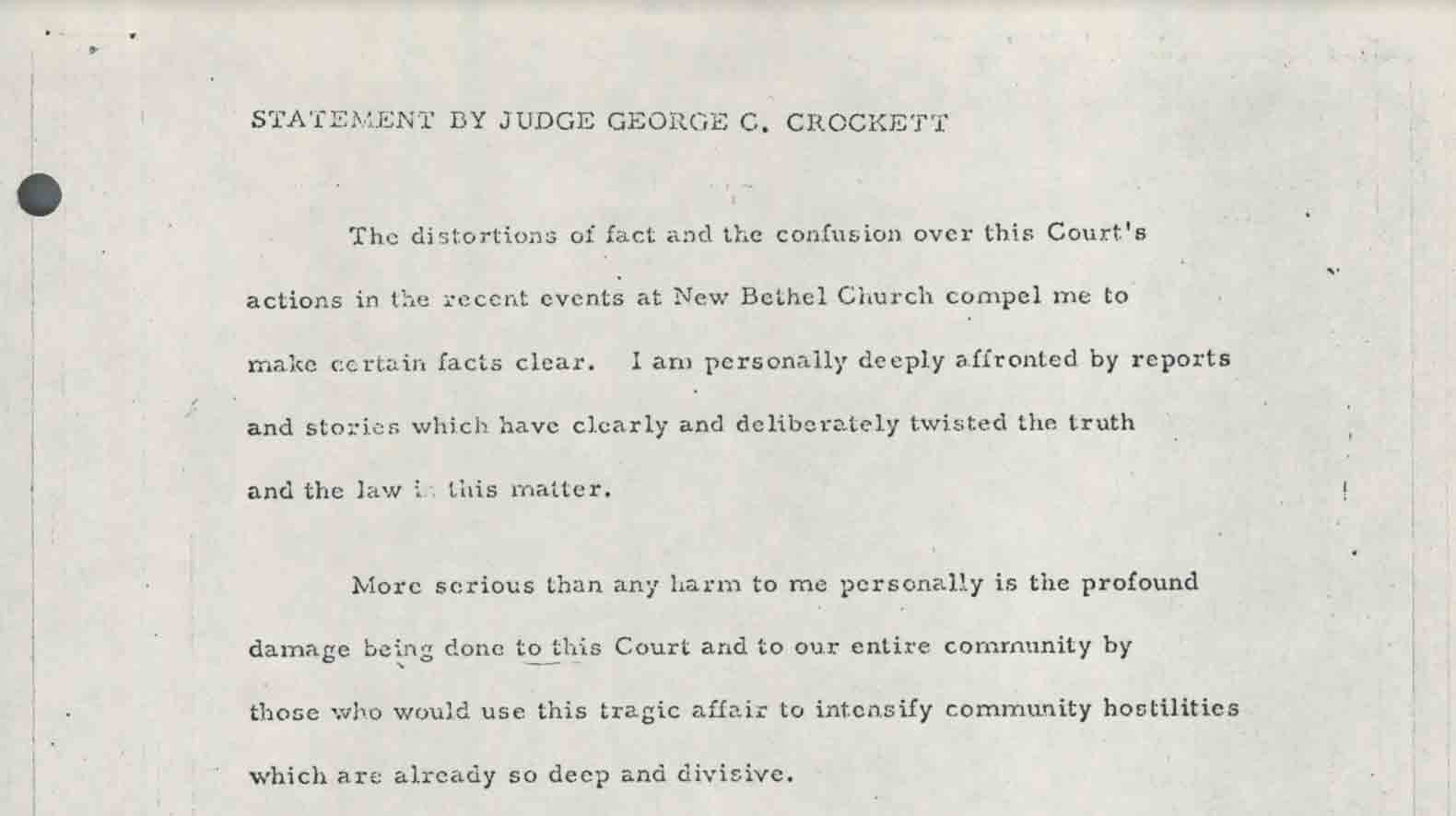

Less than a year later, the police again attacked an organized protest gathering in ways that further fueled suspicion they were actively taking revenge on blacks for rebelling. In March of 1969, the Republic of New Afrika (RNA) gathered to celebrate it’s one-year anniversary at New Bethel Church on the city’s West Side and, in response the threat of police brutality, the meeting itself was protected by armed members of the RNA. Following the meeting of approximately 200 people, a Detroit Police Department squad car pulled up to RNA security forces. Two officers, Michael Czapski and Richard Worobec got out of the car and in the confrontation that followed, Czapski was killed, Worobec was injured, and four civilians were injured. As police flooded the surrounding area, they began firing indiscriminately and rounded up over 150 civilians. RNA leader Brother Giadi (Milton Henry), who had left the meeting before the shootout, contacted State Representative James Del Rio about the chaos, and Del Rio contacted George Crockett, a black judge.

Crockett arose from bed, went to police headquarters, and found complete chaos when he got there. Although the police had rounded up more than 150 people and not taken a list of their names, they had questioned, fingerprinted, and administered nitrate tests to all 150 to see if they had fired a gun. Denied their right to legal counsel, Judge Crockett, set up court right there in the station. After Crockett demanded that all those held captive be freed or formally arrested and charged, the police called in Wayne County Prosecutor William Callahan. When Callahan promised that all irregular police procedures would be abandoned Crockett adjourned court and went home. The next day all but a few of those rounded up were set free without charges.

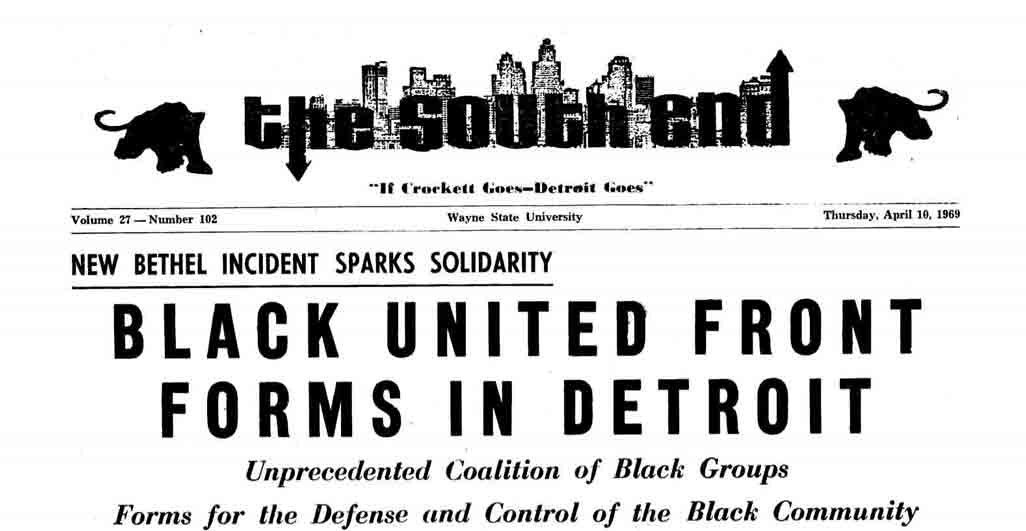

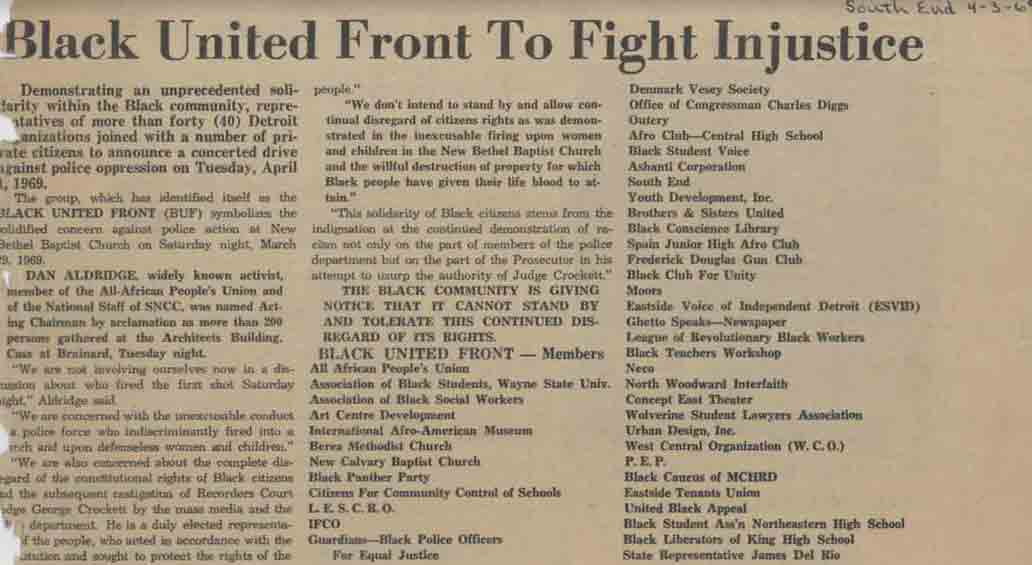

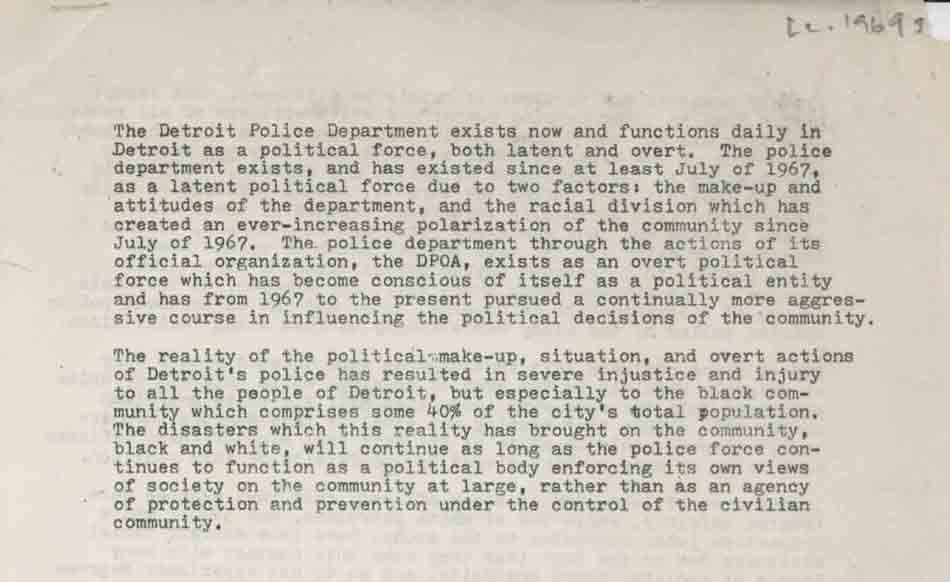

In the weeks that followed, Detroit was embroiled with tension between the police and black activists. Appalled that a black judge would interfere in their racist practices, the Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA) organized a campaign to get Crockett removed from the bench. Their main complaint was that Crockett was acting out of solidarity with black people rather than following the law. Conservative politicians responded by ordering a full investigation into Crockett’s fitness to stay on the bench. Black activists responded by formally creating a Black United Front (BUF), made up of 60 black organizations. While the DPOA took out a full-page ad in the Detroit News, the BUF organized a demonstration in support of Crockett, drawing upwards of 3,000 people. The Detroit Commission on Community Relations issued a report favorable to Judge Crockett and the controversy eventually came to rest.

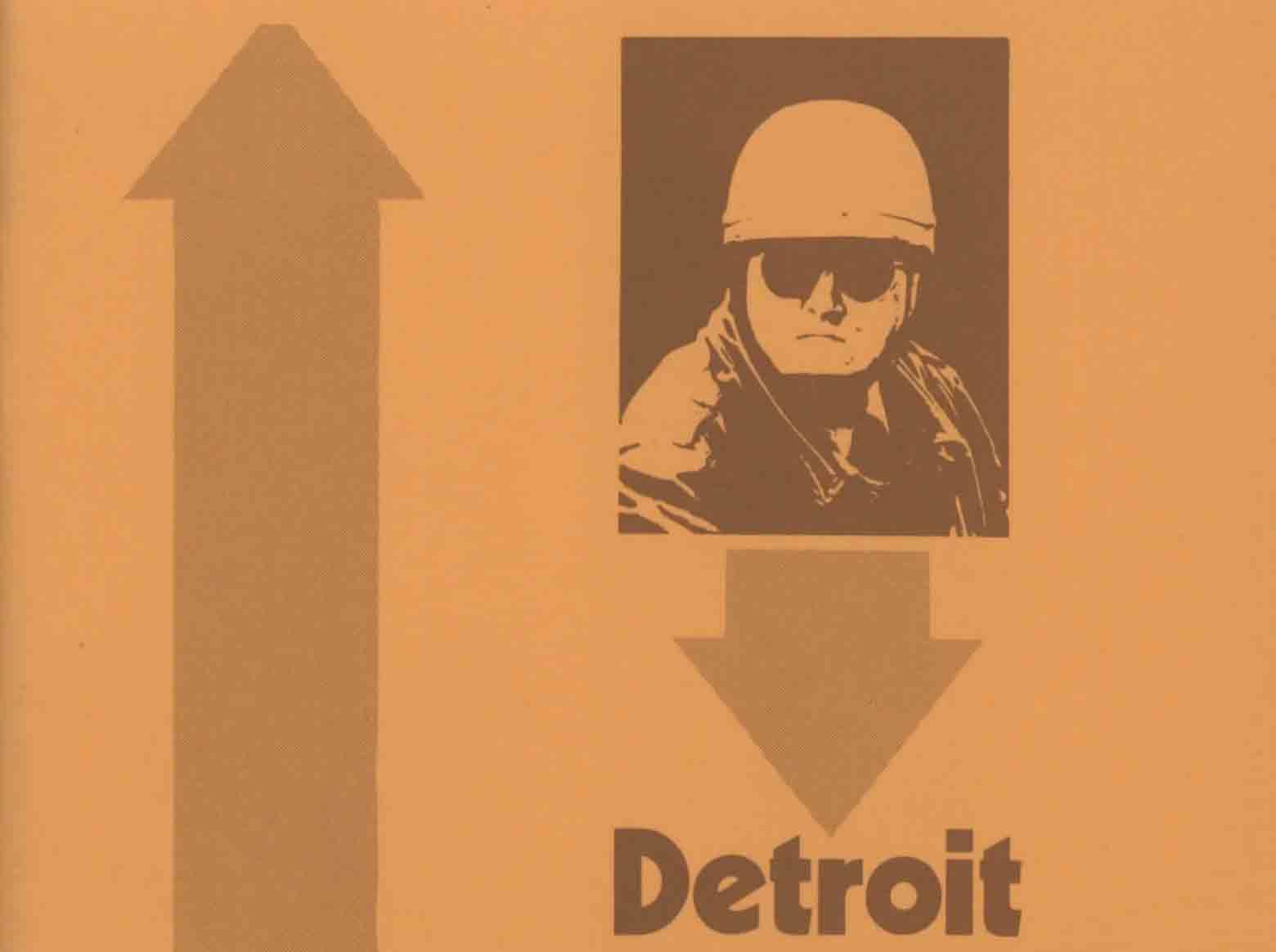

Despite Crockett’s intervention and the activism of black Detroiters, police brutality continued to climb after the Rebellion and by 1971 the police in Detroit killed more civilians than police in any other city. Most of these killings were the product of a program of the Detroit Police Department called STRESS, or Stop the Robberies Enjoy Safe Streets. STRESS was the product of the promise Mayor Gibbs made to his white constituents to restore “law and order” after the Rebellion. STRESS often employed a decoy tactic in an attempt to catch would be robbers. One STRESS officer would act as an easy target of a robbery while two officers hiding nearby would jump out and arrest would be robbers. Not only a police tactic of questionable legality, it also resulted in the deaths of ten suspects in the first nine months on 1971, nine of whom were black. By September 1973, STRESS officers killed twenty-two suspects, 95 percent of which died in decoy operations.

Black Detroiters organized against STRESS almost as soon as it emerged. In September 1971, more than 5,000 demonstrated against it, demanding that it be abolished. Similar demonstrations occurred until the mayoral election of Coleman Young who abolished the program.

References

Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, Boston, South End Press, 1998

Heather Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City, Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2001

Clips from 2018 interviews with veteran Detroit activists Elliott Hall and JoAnn Watson, in which they discuss police brutality and community responses to STRESS. –Videography: 248 Pencils

Mayor Jerome Cavanagh is confronted by protestors during the Poor People\’s Campaign in Detroit in March 1968. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clips from 2018 interviews with veteran Detroit activists Frank Joyce, JoAnn Watson, Dan Aldridge, and Elliott Hall, in which they discuss the \”New Bethel incident,\” an infamous shoot-out between the Detroit Police Department and the Republic of New Africa in 1969. –Videography: 248 Pencils

The South End, vol 27, no 102, April 10, 1969. This edition features coverage of the New Bethel Incident, formation of the Black United Front, and an analysis of racist media coverage of the incident. –Credit: Files of David Goldberg

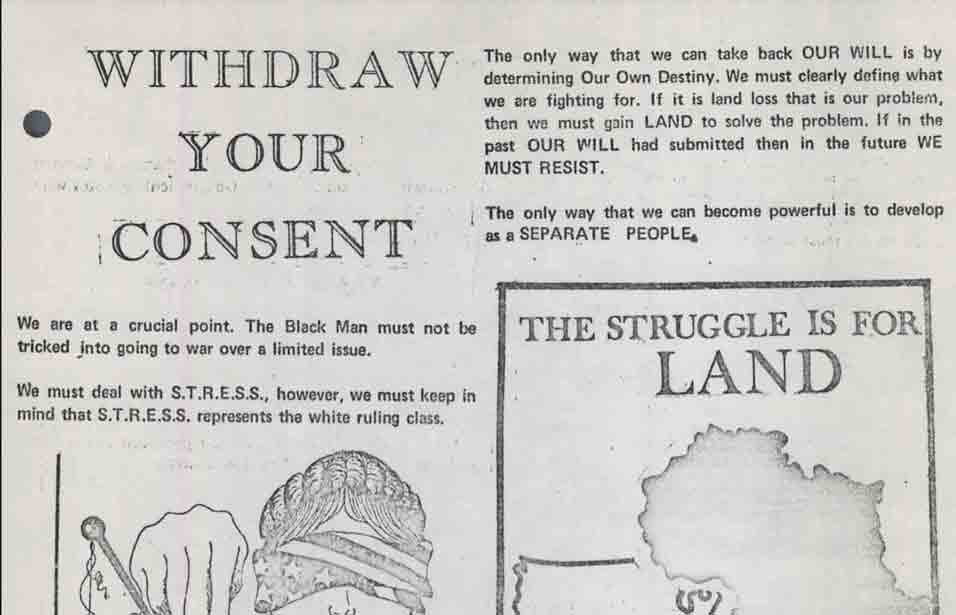

Pamphlet, \”Detroit Under STRESS,\” published by From the Ground Up, 1973. From the Ground Up, a White political organization, believed the STRESS program intimidated the Black community and perpetuated the existing power structures and racial divisions. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

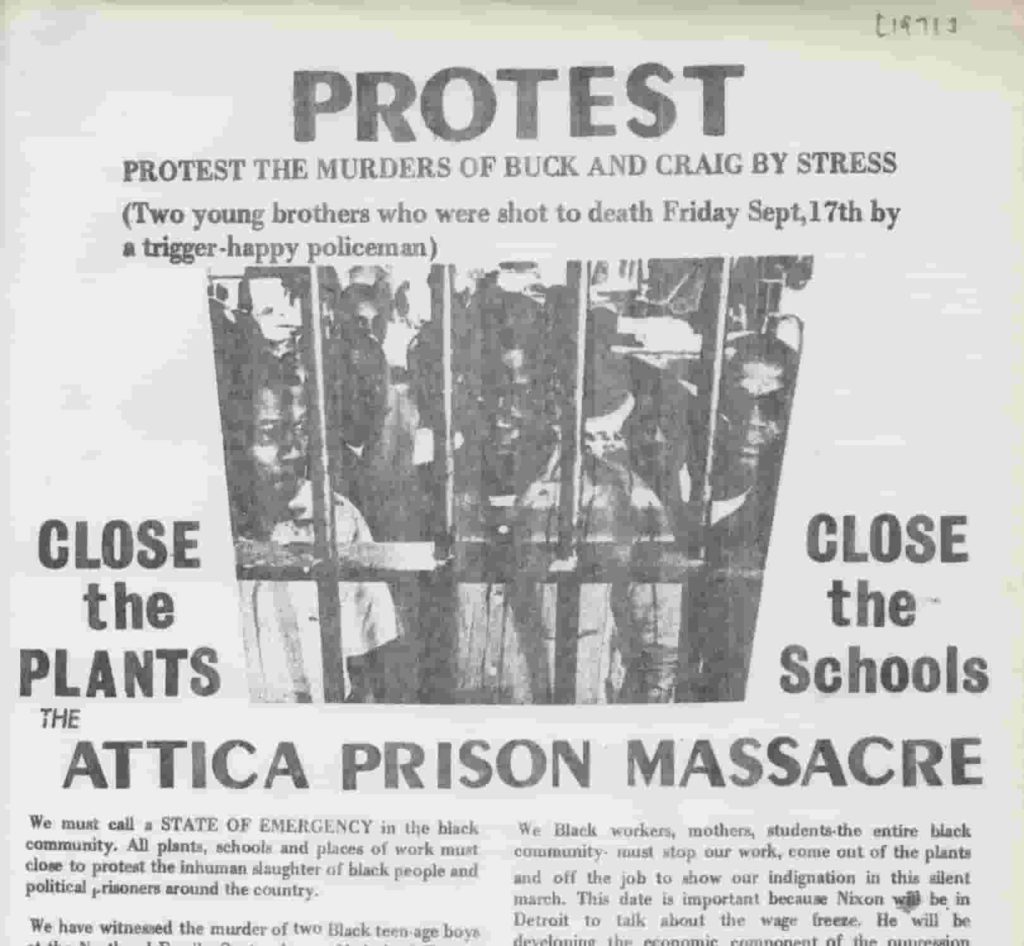

Five thousand gather in downtown Detroit on September 23, 1971 to protest the killing of two Black teenagers, Craig Mitchell and Ricardo Buck, by STRESS officer Richard Worobec. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Explore The Archives

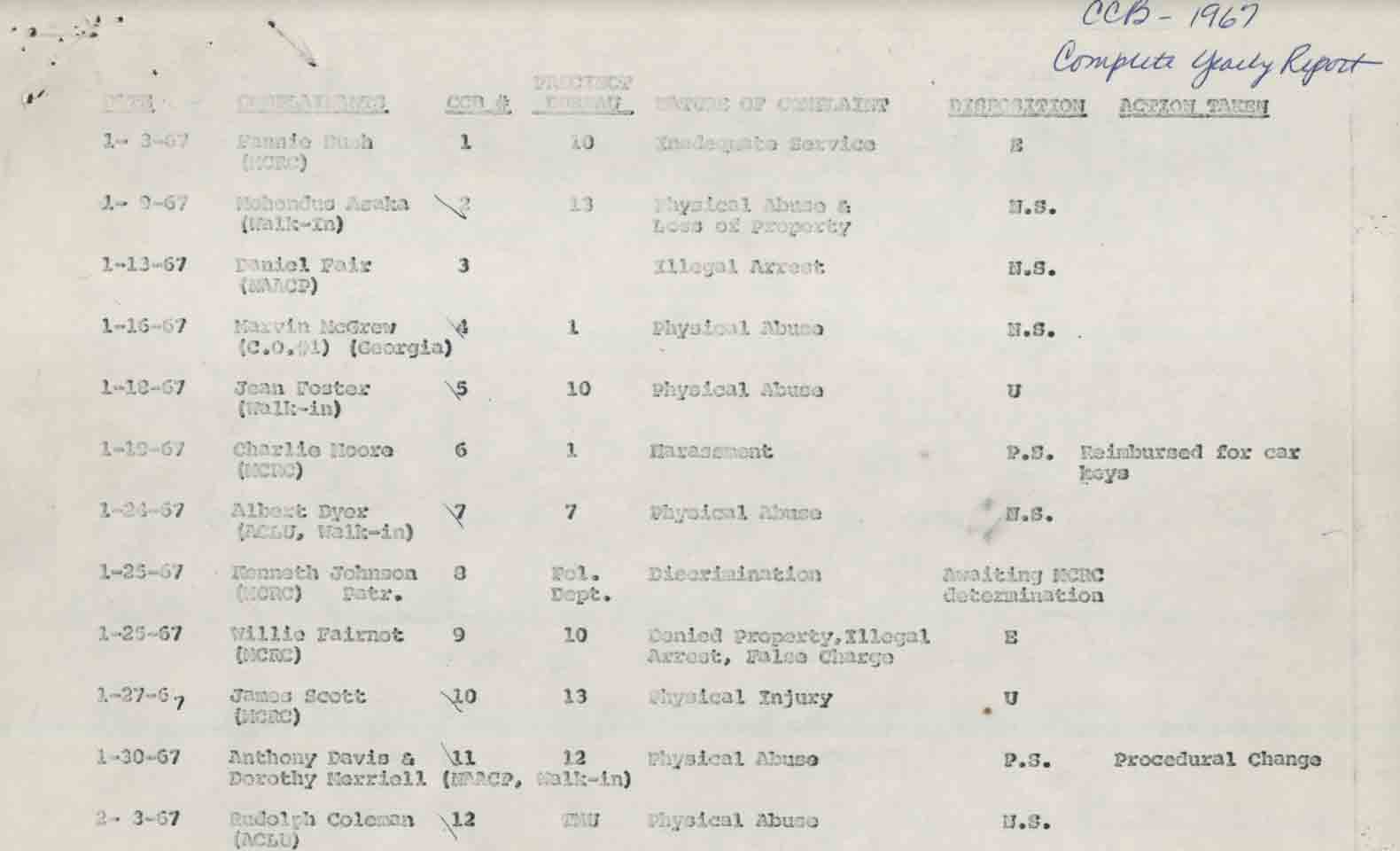

According to the complete yearly report from the Detroit Police Department\’s Citizen Complaint Bureau for 1967, few substantive actions were taken against offending police officers. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

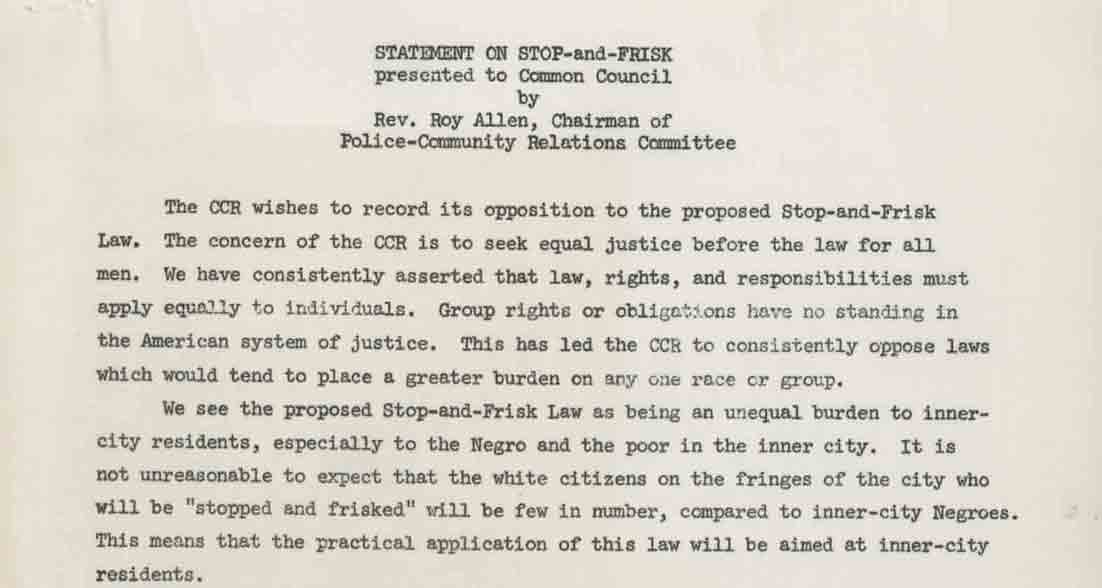

Statement presented to Common Council by Rev. Roy Allen, Chairman of the Police-Community Relations Committee, stating his opposition to a proposed Stop-and-Frisk law (February 28, 1968). –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

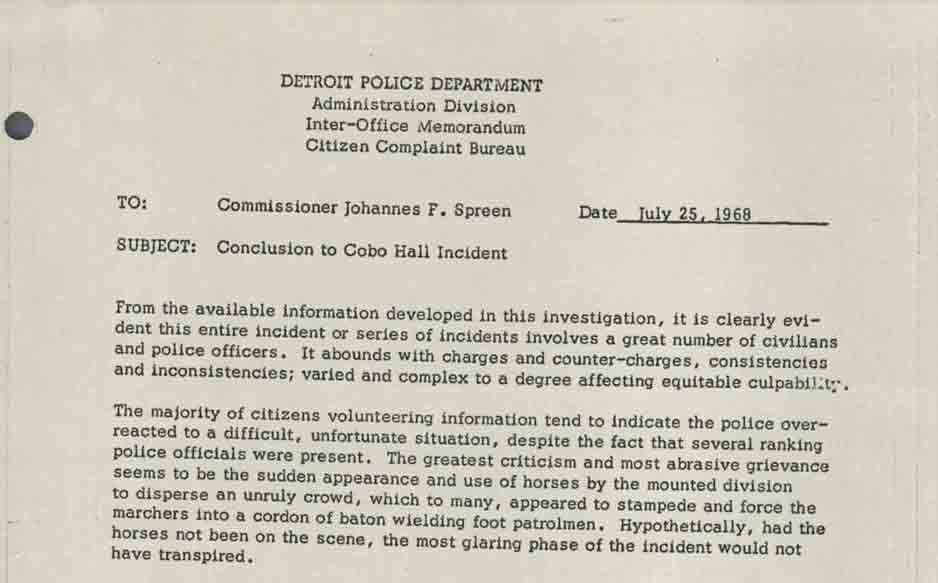

Detroit Police Department memo to Commissioner Johannes F. Spreen, \”Conclusion to Cobo Hall Incident.\” On May 13, 1968, there was an altercation between police and members of the Midwest Caravan PPC. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

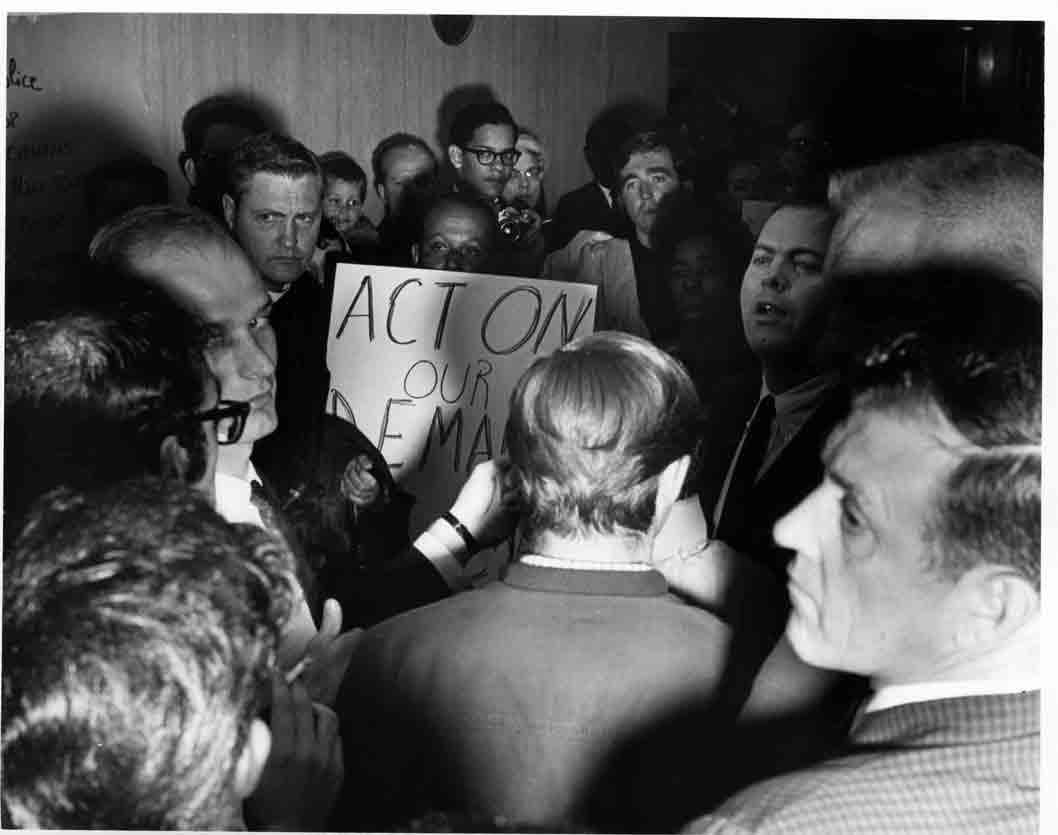

Protestors confront Detroit Mayor Jerome Cavanagh in the late 1960s. This photo was likely taken during protests over police brutality at the 1968 Poor People\’s Campaign in Detroit.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

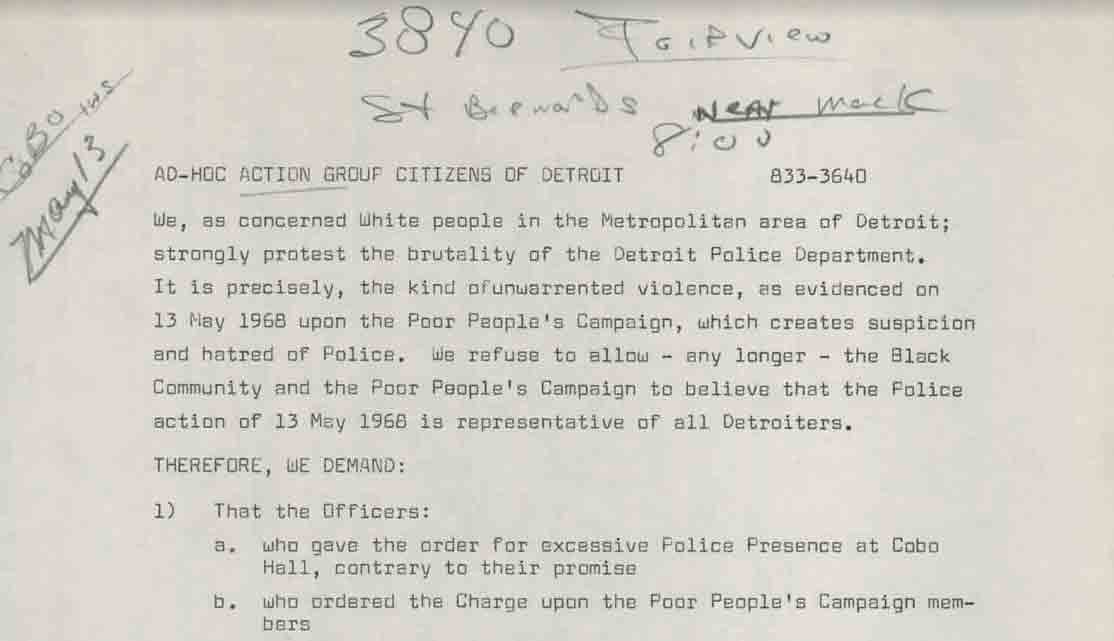

List of demands of the Ad-Hoc Action Group Citizens of Detroit, a group of White citizens protesting police brutality (May 1968). –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

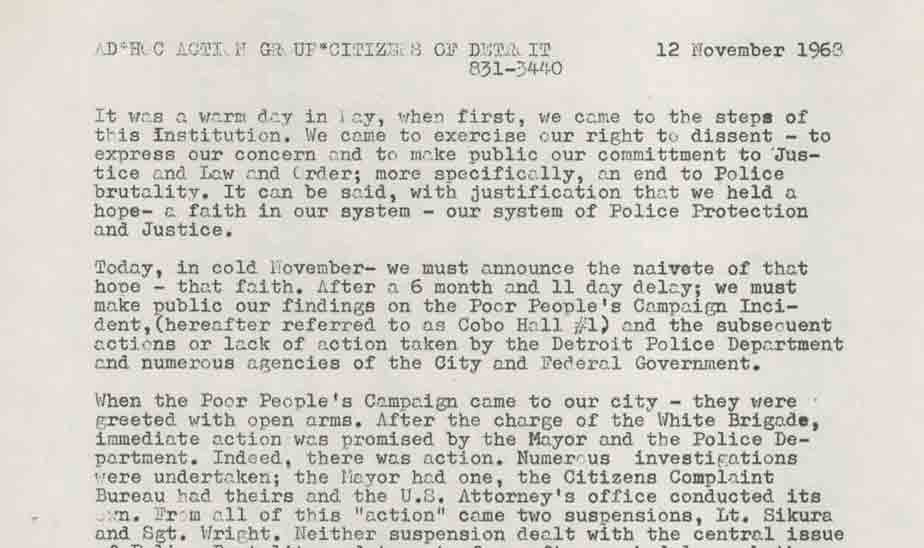

Statement of the Ad-Hoc Action Group Citizens of Detroit on police incidents at Cobo Hall, issued November 12, 1968. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

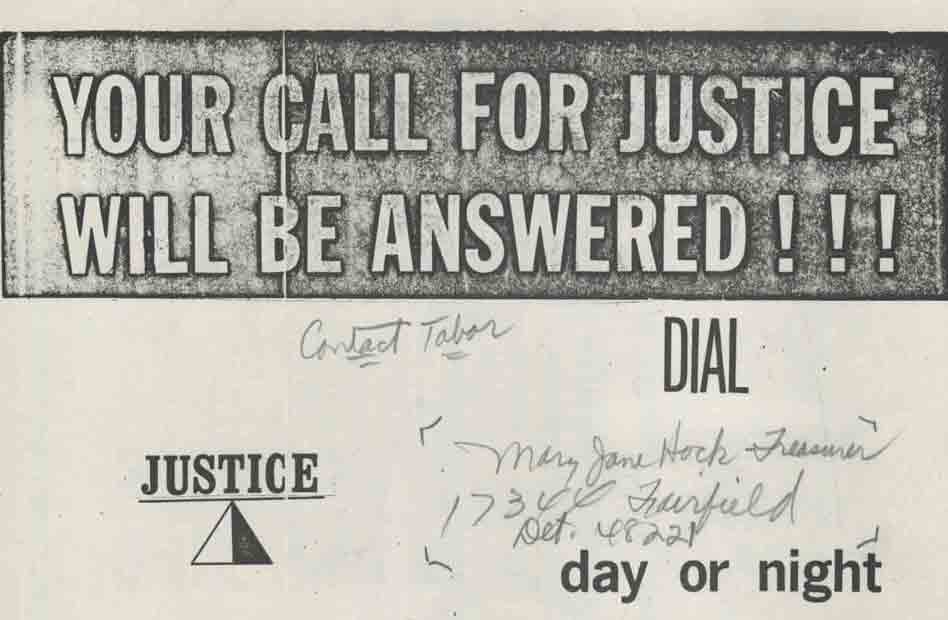

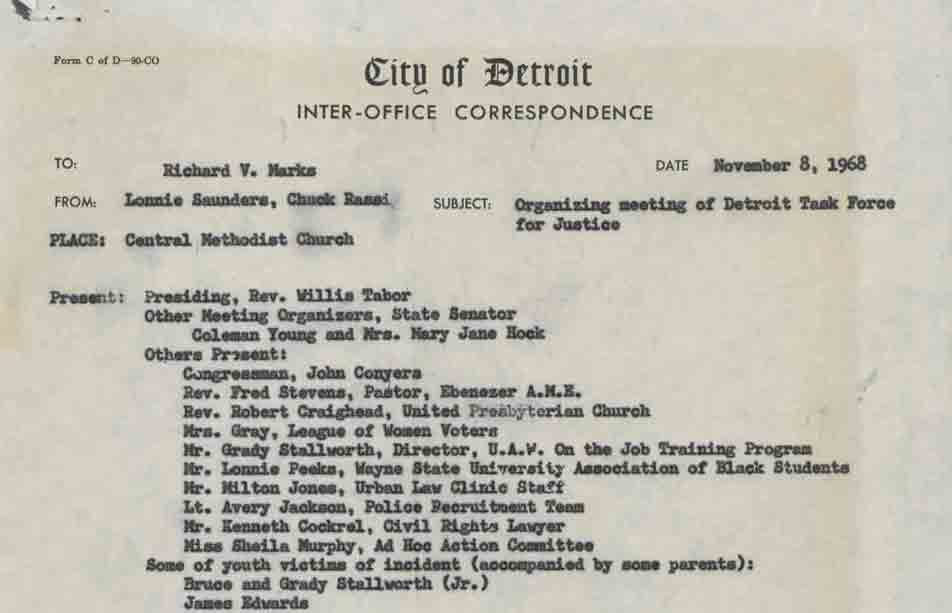

Detroit Task Force for Justice flyer and statement of purpose. The Task Force provided legal assistance for those mistreated by police (November 1968). –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A message from Police Commissioner Patrick V. Murphy to Detroit Police officers on fatalities in the line of duty. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

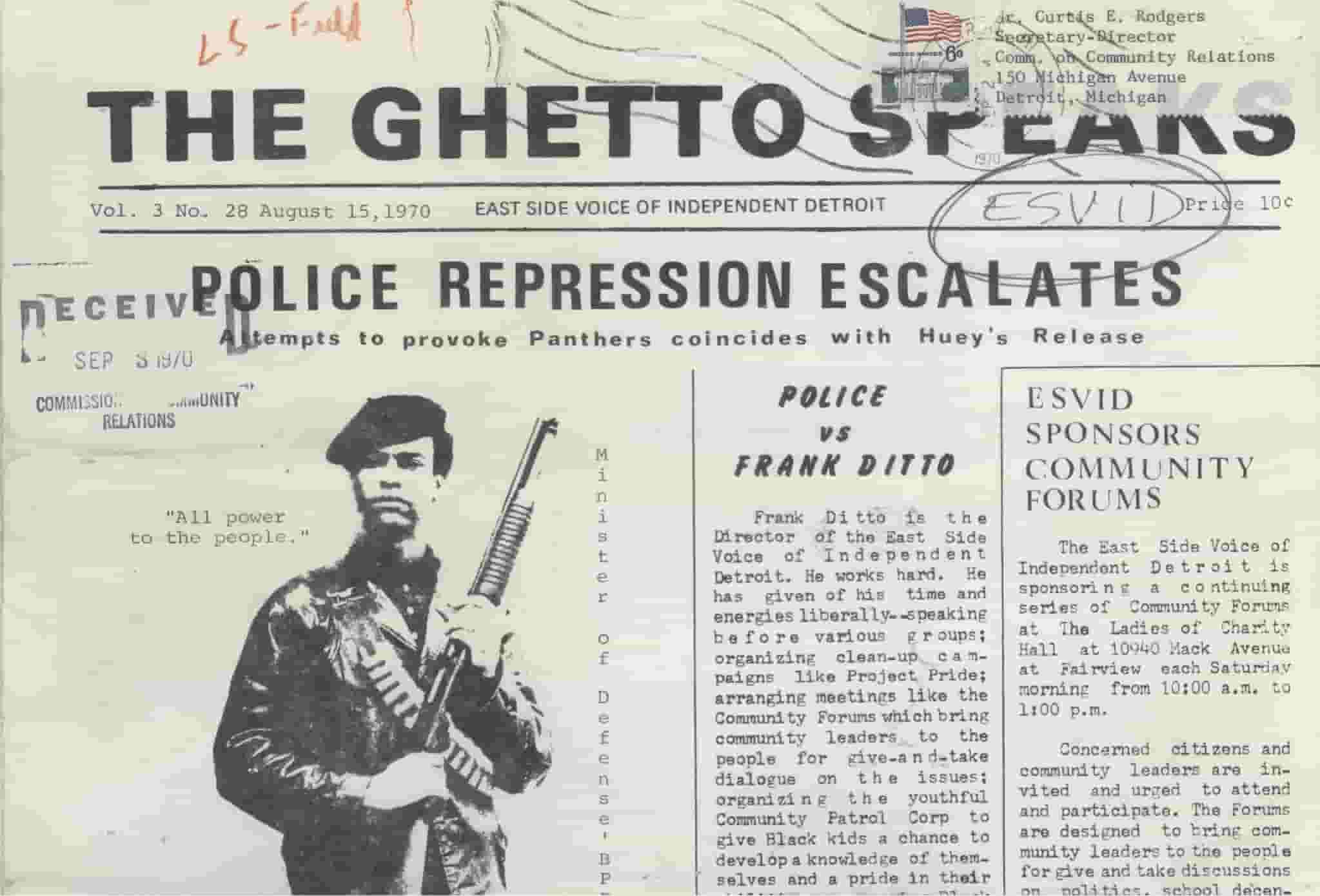

The Ghetto Speaks: East Side Voice of Independent Detroit, vol. 3, no. 28 (August 15, 1970). Headline on the police repression of the Black Panther Party. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

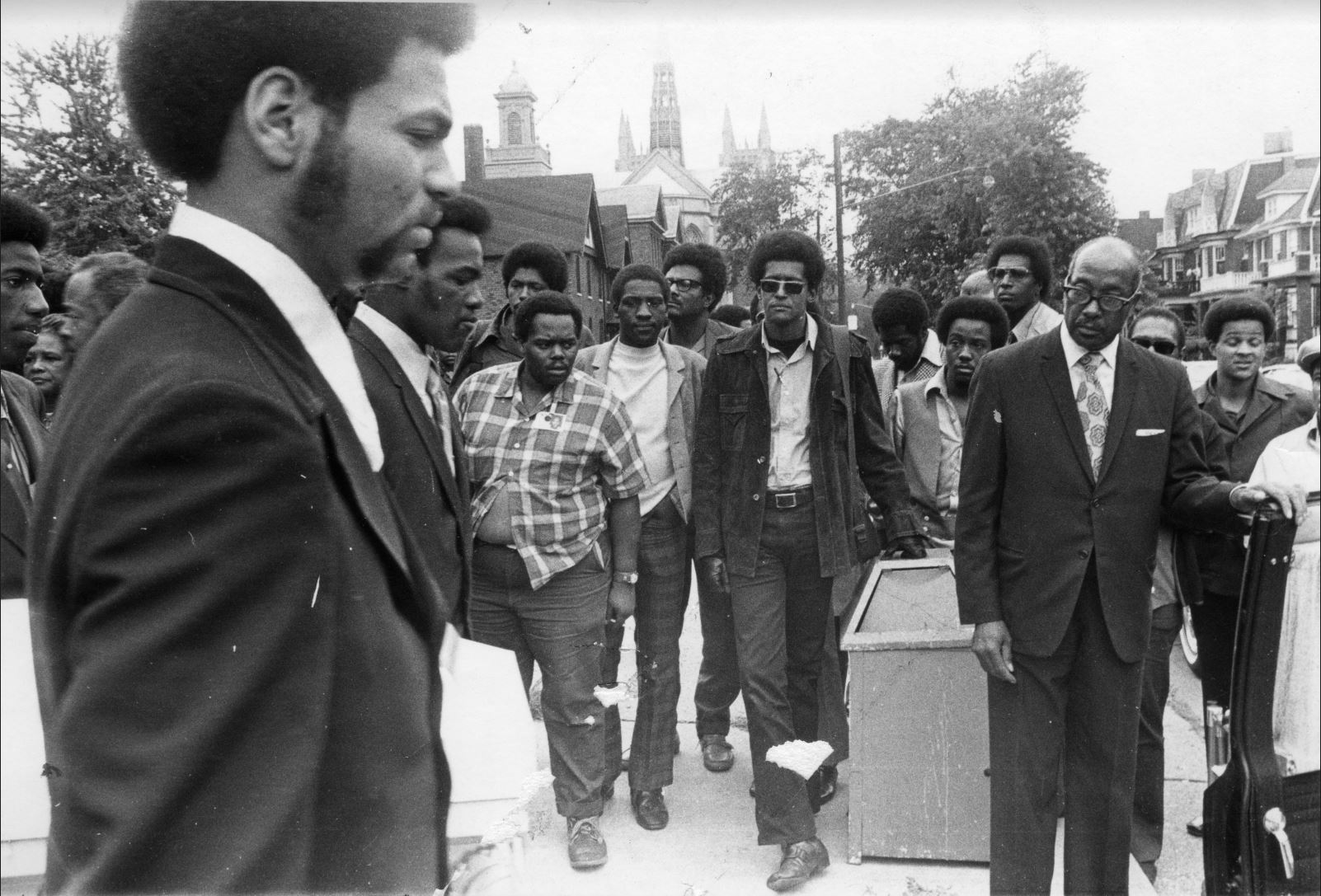

Ken Cockrel (center), Mike Hamlin (behind Cockrel\’s right shoulder), and others watch as 14-year-old Craig Mitchell\’s casket is carried to a hearst. Mitchell and 15-year-old Ricardo Buck were killed by STRESS officer Richard Worobec in September 1971. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

On September 23, 1971, several community organizations (including the Labor Defense Coalition, the Black Workers Congress, and others) sponsored a silent march to protest the murder of Black people and political prisoners. The march coincided with a visit from President Nixon. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

A memo to the Commission on Community Relations (CCR) from the Police-Community Relations Committee and Staff on the Detroit Police Department\’s STRESS Program (October 2, 1971). The program, Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets, began that previous January. Many community groups were opposed to the program, particularly after the killing of Black citizens by STRESS officers. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Attorney Kenneth Cockrel addresses the audience at an Anti-STRESS (Stop the Robberies and Enjoy Safe Streets) event in Detroit. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Memo to the Commission on Community Relations, \”Changes in the Detroit Police Department\’s STRESS Program,\” (March 22, 1972). After criticism and a large number of citizen fatalities, Police Commissioner John F. Nichols announced stricter testing and supervision of officers. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

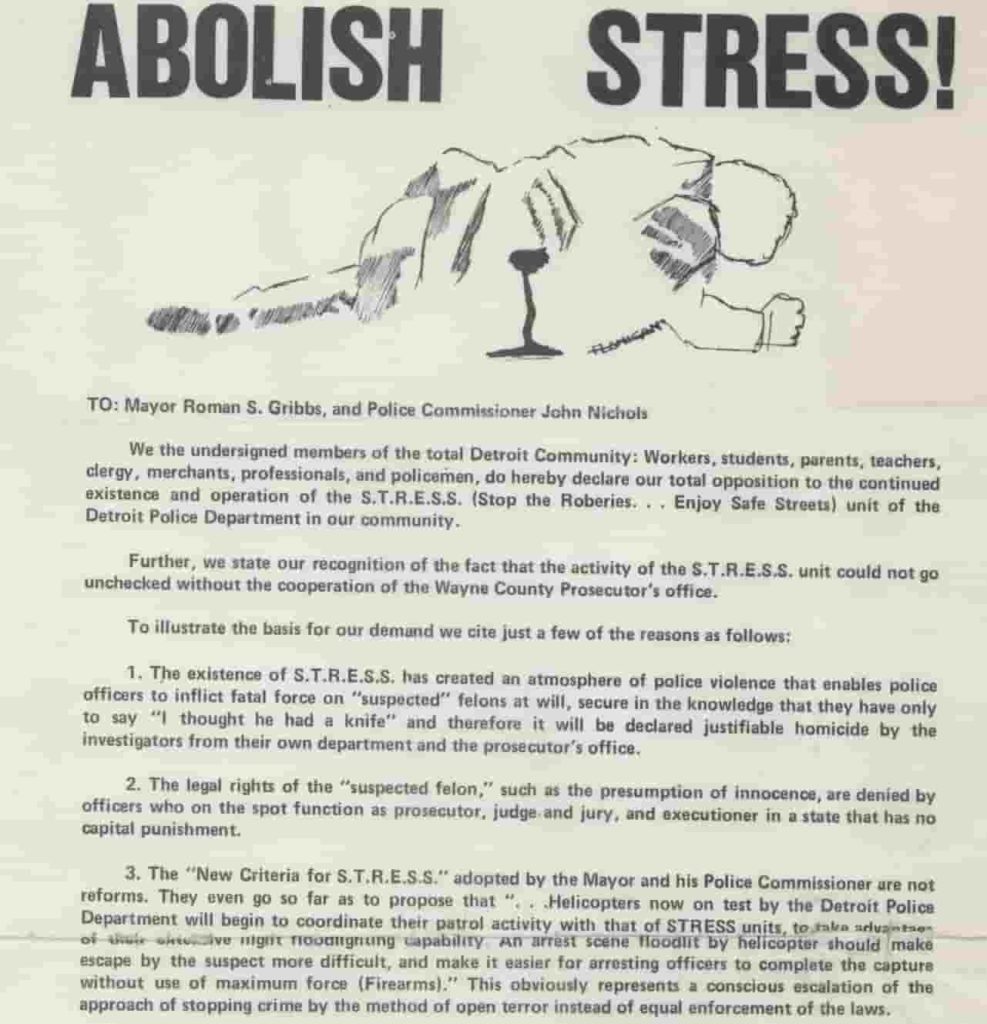

Petition from the Labor Defense Coalition demanding the immediate elimination of the STRESS program, 1972. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Women of From the Ground Up demand the abolishment of STRESS after the murder of Joan Davis. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

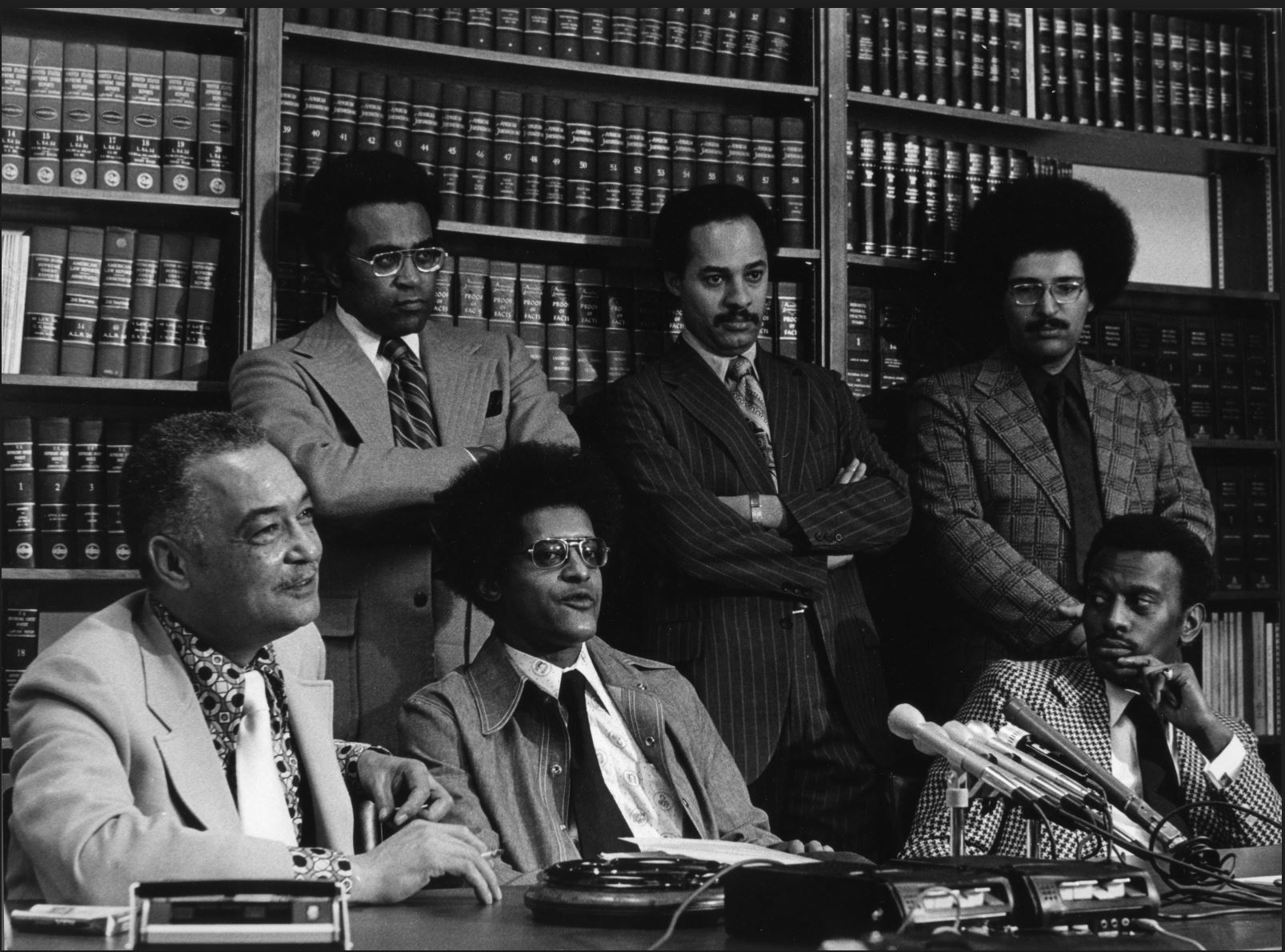

Ken Cockrel (center) speaks at a press conference in the early 1970s demanding the abolition of STRESS. Cockrel played a leading role in organizing efforts to resist and dismantle STRESS, which propelled Coleman A. Young to become mayor in 1973.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Coleman A. Young and Ken Cockrel at a press conference in the early 1970s. STRESS was one of the central issues of the 1973 mayoral campaign won by Coleman A. Young. Young ran on a promise to dismantle STRESS, which he kept once he got into office.–Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

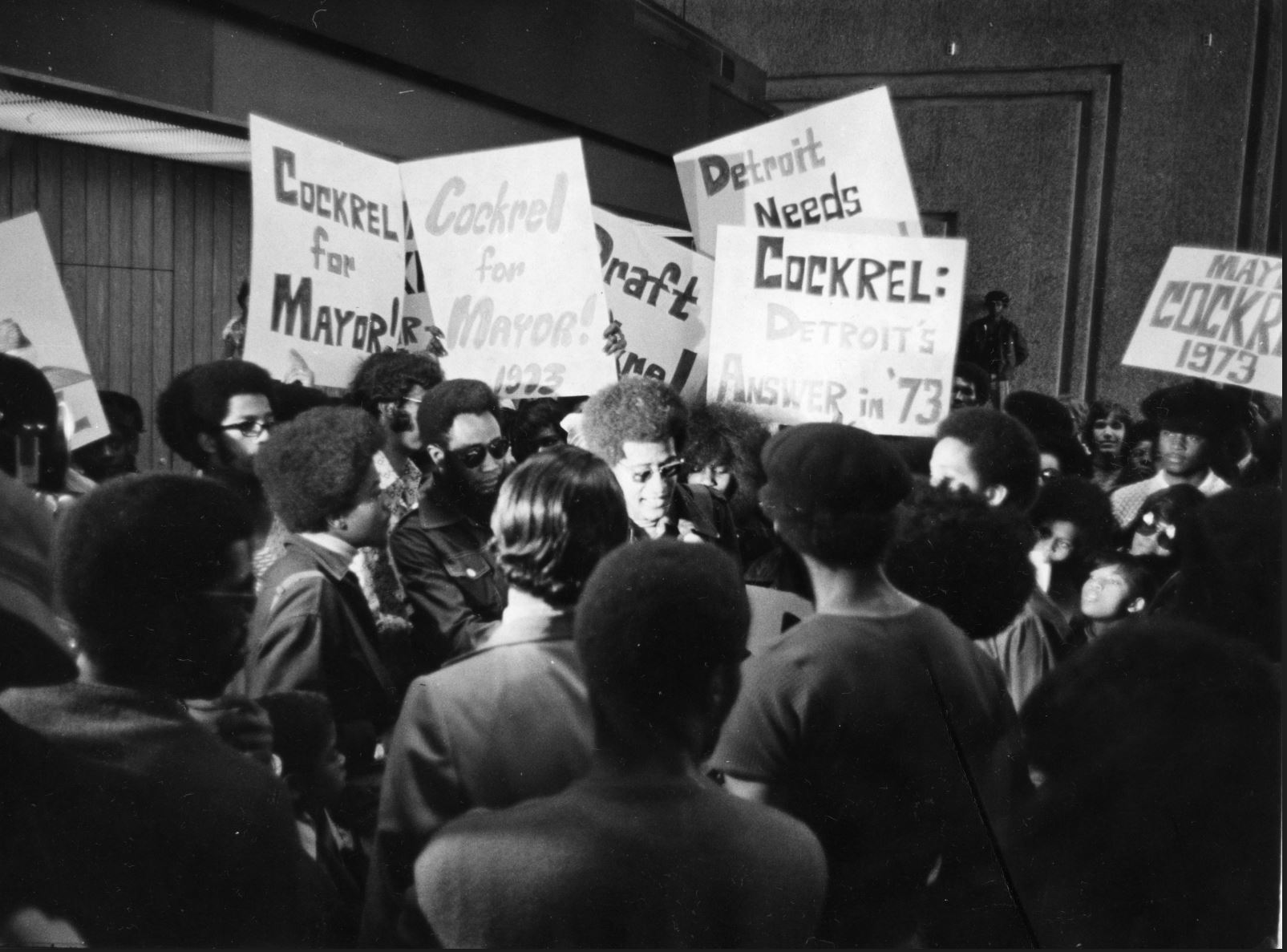

Ken Cockrel at a rally to support a potential campaign for the 1973 mayoral election. Cockrel\’s fierce opposition to STRESS and steadfast legal defense of Black citizens charged with STRESS-related crimes made him one of Detroit\’s leading political figures. Cockrel eventually left the election to Coleman A. Young, however, who became the first African American mayor of Detroit. -Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Statement by Judge George C. Crockett following the New Bethel Church incident, 1969. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.