Electoral Politics

Beginning in the 1950s, black Detroiters increasingly began to participate in electoral politics with inconsistent results. Because the city had at-large elections to city council rather than ward or district-based elections, the residential segregation of blacks did not result in political power at the municipal level. However, because residential segregation did give them the political power to elect black politicians at the state level, between 1946 and 1962, eight blacks won election to the Michigan State legislature. In 1954, thanks to a coalition of liberal labor and civil rights organizations, Charles Diggs Jr. was elected to Congress from Michigan’s 13th district and re-elected in 1956, 1958.

Learning from the success of Diggs’ strategy, a coalition of liberal labor and civil rights groups organized a campaign to elect Detroit’s first black city council member, William T. Patrick in 1957. Rather than make explicit appeals to black voters on the basis of race, Patrick’s campaign sought ways to make him appealing to white voters. Knowing that the black vote was his, Patrick aligned himself with council member Ed Carey, taking him into Detroit’s black neighborhoods, with Carey doing the same for Patrick. Although Polish whites largely refused to vote for Patrick, his background as a professional and his endorsement by the city’s liberal-labor coalition made him electable to other white voters. He was re-elected multiple times until he resigned in 1963 to work for Bell Telephone.

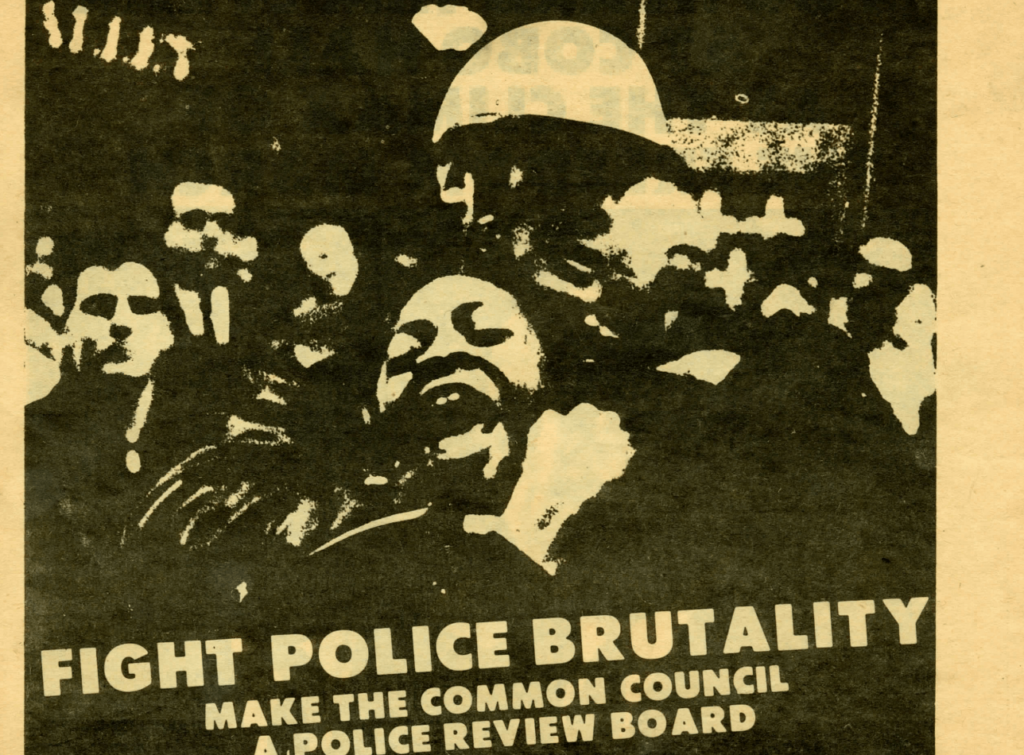

In 1961, black voters were the swing votes that elected Jerome Cavanagh Mayor of the city and demonstrated to black people new evidence of their political power. In the run-up to the 1961 election incumbent Louis Mariani was heavily favored and endorsed by the United Auto Workers. Black Detroiters voiced fierce opposition to Mariani, holding him largely responsible for rampant police brutality in the city. With the Trade Union Leadership Council endorsing Cavanagh, black people gained access to an organizational structure to organize a campaign they called “Phouie on Louie,” which was as much a campaign against Mariani as it was for Cavanagh. Cavanagh beat Mariani by more than 50,000 votes and promised to black Detroiters a black police commissioner and speedy integration throughout the city. While Cavanagh made good on some of his promises, he implemented integration slower than most blacks believed he should and because they now believed in their own electoral power, many turned increasingly toward independent black politics and away from liberal cross-race political coalitions.

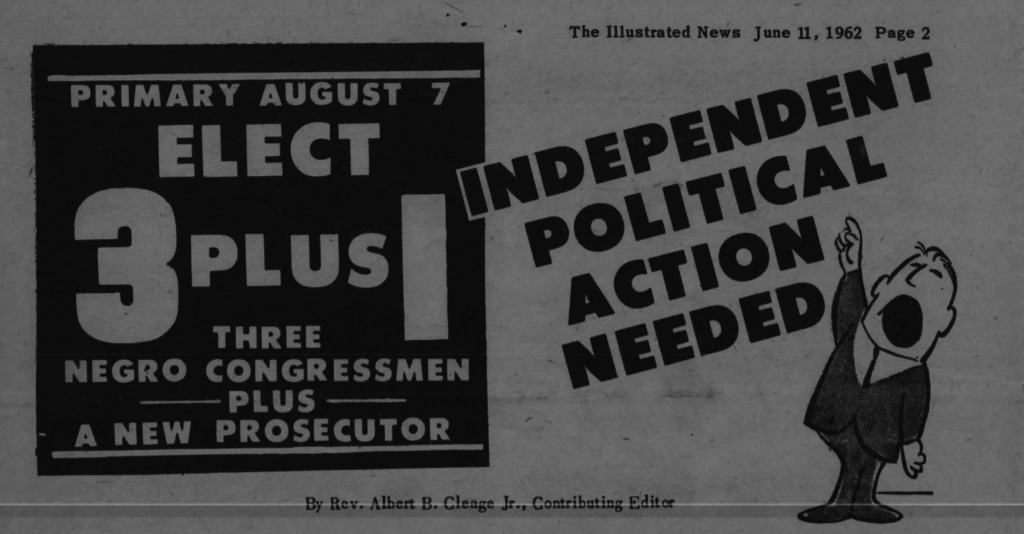

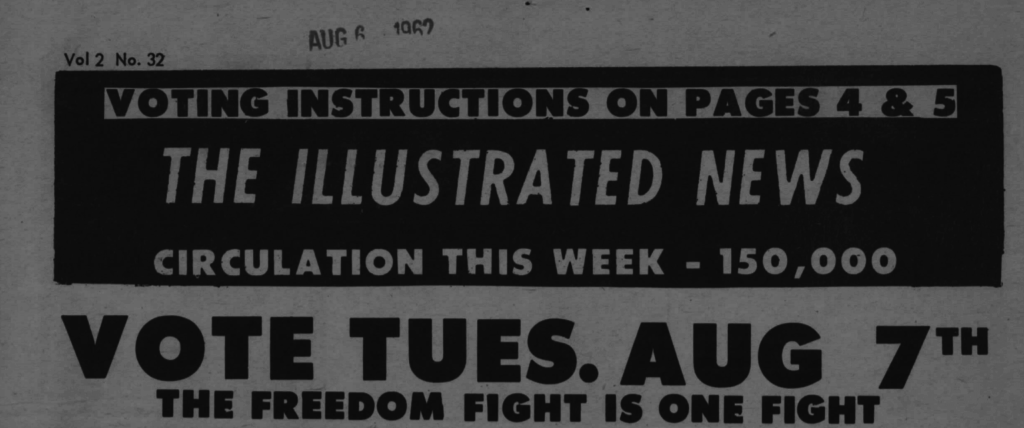

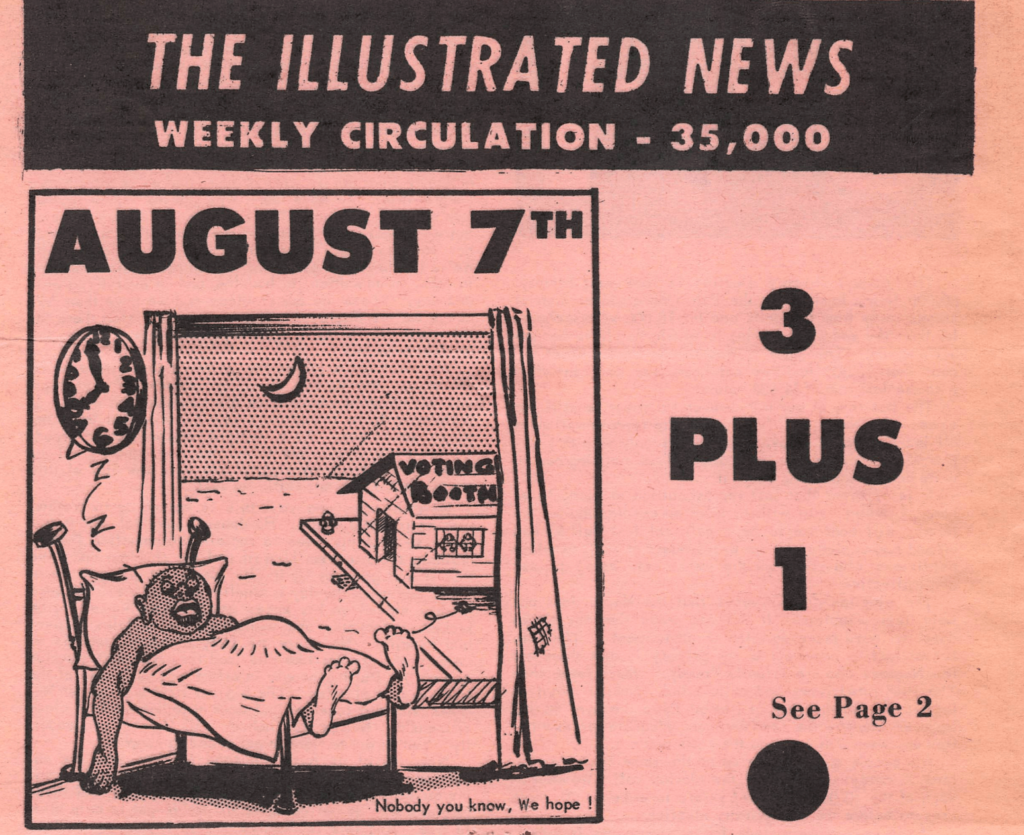

Rev. Albert Cleage is the best symbol of black Detroiter’s turn towards independent black electoral politics. In 1962, Cleage organized a campaign to elect three black congressmen and one prosecutor with the slogan, “Elect 3 Plus 1.” The goal to elect three black congress people did not come from a whim. After careful and thoughtful study of how Detroit’s black population had grown and how racial segregation had forced it to concentrate in three districts, Cleage perceived a realistic opportunity to elect three black people to Congress. The campaign took on increased urgency because both Republicans and Democrats were aligned in support of House Bill 88, to gerrymander the black majority in the 11th, 13th, and 15th districts all into the 13th district, which Diggs had represented since 1954. When blacks and whites alike accused Cleage’s campaign to elect only blacks to Congress as racist, Cleage replied “this is not racism this is democracy.” As 35% of Detroit, Cleage campaigned that black people were entitled to 35% of political positions related to the city and could secure that if they did not allow labor or liberal candidates to split their vote.

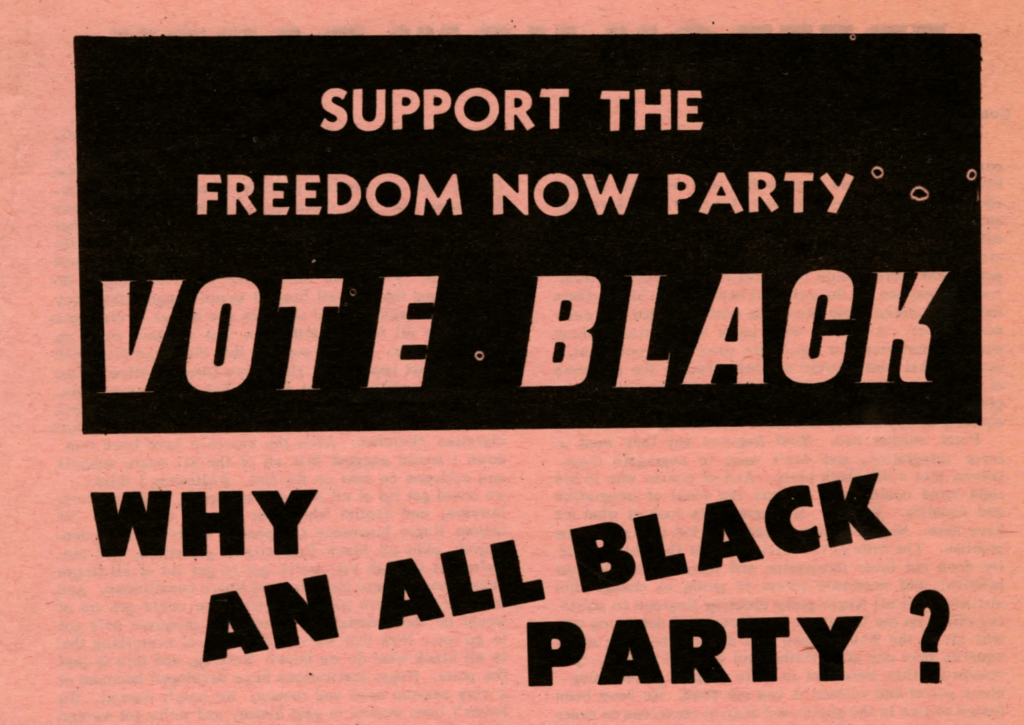

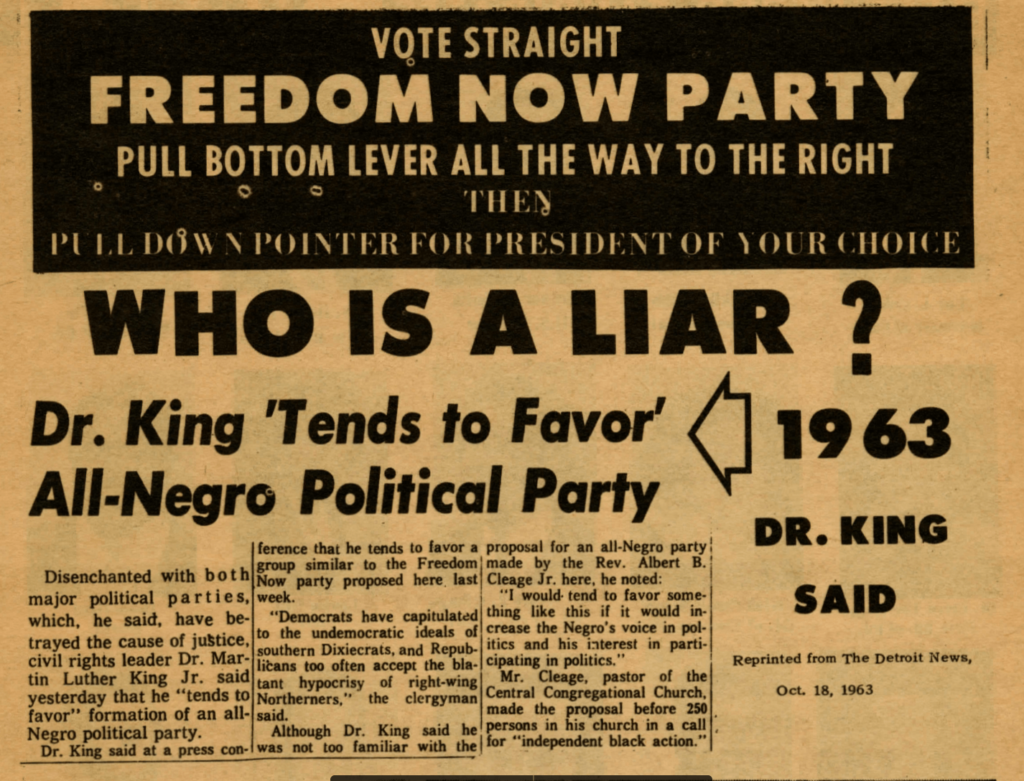

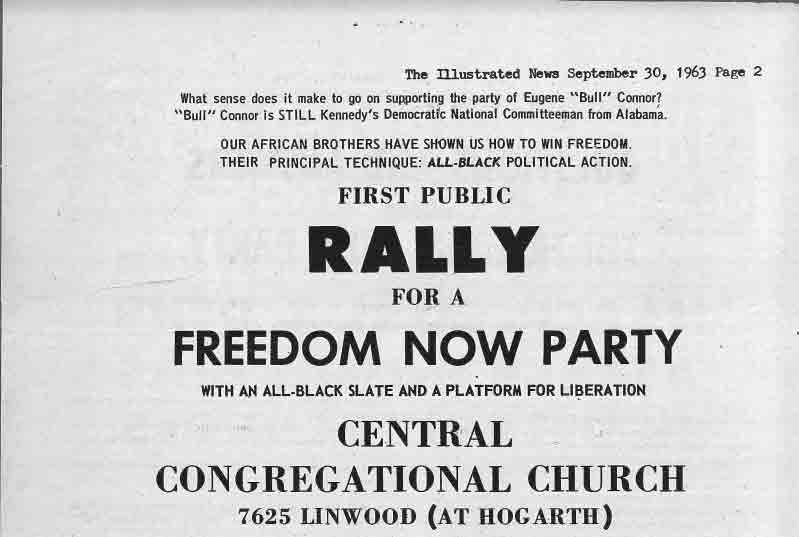

Although they lost the 3 plus 1 more campaign in 1962, in 1964, Cleage played a major role in organizing the Michigan branch of the Freedom Now Party (FNP), a national all-black political party. Building on the 3 plus 1 campaign and the election of Mayor Cavanagh, the FNP stressed that because black votes had carried white candidates, “the Negro holds the balance of power” in elections. Based on this power, the FNP maintained that if black people broke with the Democratic Party and created their own agenda, they could get one of the major parties to accept it by promising to withhold their votes until one party endorsed it. This way, the FNP campaigned, black people could exercise the power needed to hold politicians from each party accountable to the promises they made to black voters.

Due to the excellent organizing by black Detroiters, the FNP got on statewide ballots in Michigan and ran an entire slate of 39 candidates, all of whom were black with the exception of Chinese-American Grace Lee Boggs. On election night early returns reported that the FNP had received 40,000 votes, which would have secured them a place on the ballot in future elections. However, in the morning the official vote count was proclaimed to be less than 10,000. Some FNP members and candidates suspected that their votes had been stolen while others believed the early returns were just a reporting error.

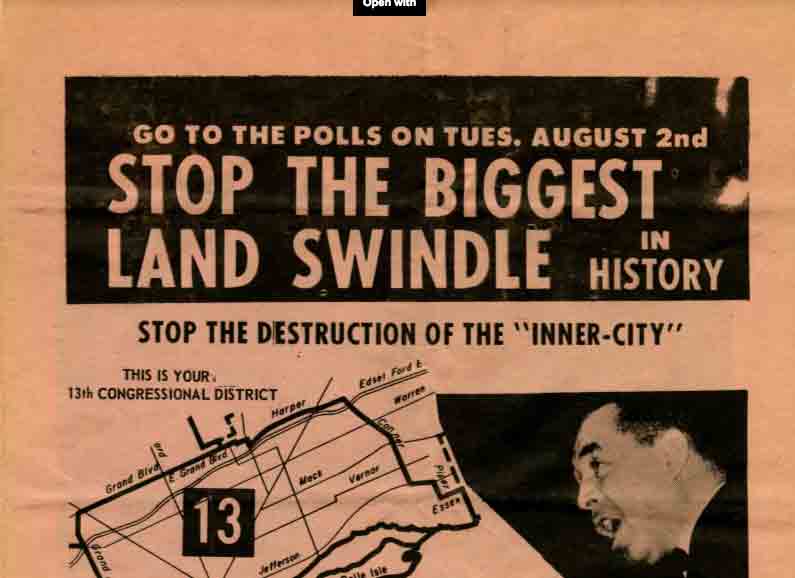

In 1966, Cleage ran for office once again as Democratic congressman in the 13th District. His campaign was part of a two-person slate, including Kenny Cockerell, who ran for State Representative in the 11th District. Cleage ran on a platform to stop urban renewal, calling it “The Biggest Land Swindle in History.” Although Cleage and Cockerell lost the campaign, Cockerell would become a city council member in the 1970s and Cleage was instrumental in organizing an entirely black slate of candidates after the 1967 Rebellion that played a role in getting Coleman A. Young elected as the first black mayor of Detroit in 1973.

References

Matthew Birkhold, Theory and Practice: Organic Intellectuals and Revolutionary Ideas in Detroit’s Black Power Movement, Binghamton University, Doctoral Dissertation, 2016

Angela Dillard, Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2009

Illustrated News, accessible at http://findingeliza.com

Clip from a 1988 interview with Congressman John Conyers, in which he describes how police brutality in Detroit influenced the 1961 Mayoral election of Jerome Cavanagh. –Credit: Henry Hampton Collection, Washington University Libraries

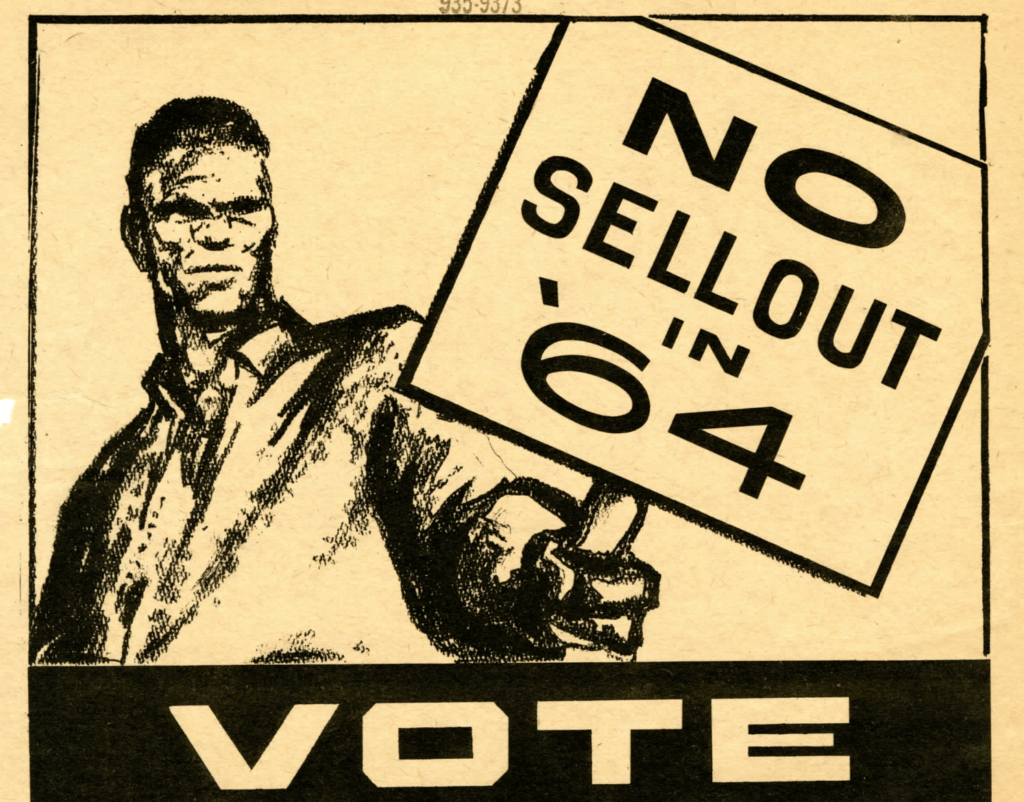

Call to elect “three Negro congressmen plus a new prosecutor.” Illustrated News, Vol. 2, No. 31, July 30, 1962. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

“Questions and Answers About the Freedom Now Party” by LaMar Barron, Acting Chairman of the Michigan Committee for a Freedom Now Party. Vol. 3, No. 20, September 30, 1963. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

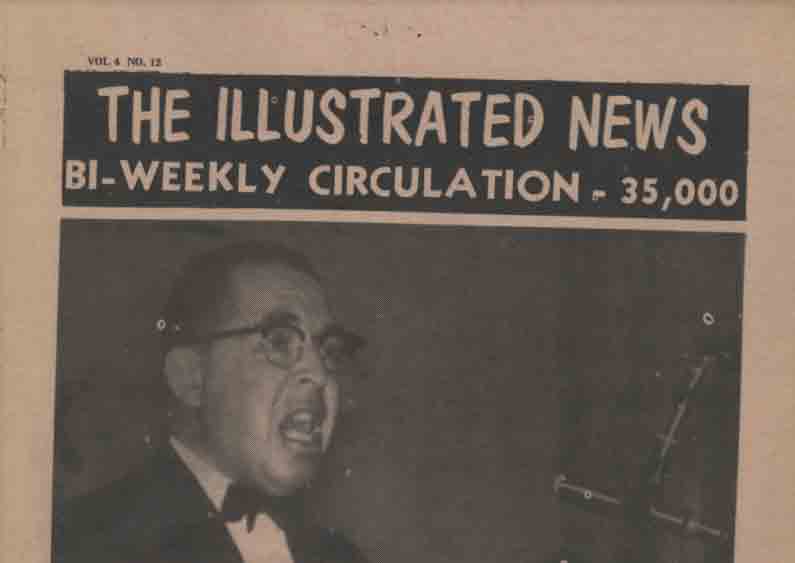

In 1964, the Reverend Albert B. Cleage, Jr. ran for Michigan governor under the Freedom Now Party. Illustrated News, Vol. 4, No. 12, September 28, 1964. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

In 1965, the Reverend Albert B. Cleage, Jr. ran for Detroit’s Common Council. He campaigned on a promise to fight police brutality and stop the destruction of the inner-city through urban renewal. “Stop the Biggest Land Swindle in History. Stop the Destruction of the ‘Inner-City.'” –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives