Tenant Organizing

and Community Control of Housing

A significant movement for community control of housing emerged in Detroit after the Rebellion, related in part to the City-wide Citizen Action Committee’s (CCAC) demand that the black community have control over post-Rebellion reconstruction. In the fall of 1967, the leadership of the CCAC developed a proposal for economic development measures that could lead reconstruction efforts. Their plan called for the creation of a back owned bank that could handle money made available for renewal projects, an Inner City Business Improvement Forum, a non-profit black business incubator, and a black housing and land development company that would buy out slumlords, rehabilitate slum housing using black construction firms, and turn the housing into co-ops. Despite constant protest by the CCAC and other black groups, the New Detroit Committee began awarding reconstruction contracts to white companies without consulting the CCAC or any other black groups. From the NDC’s decisions, CCAC leadership concluded that their protests would not be enough to gain community control of reconstruction and formed the Federation for Self-Determination (FSD) to lobby money for its reconstruction plan.

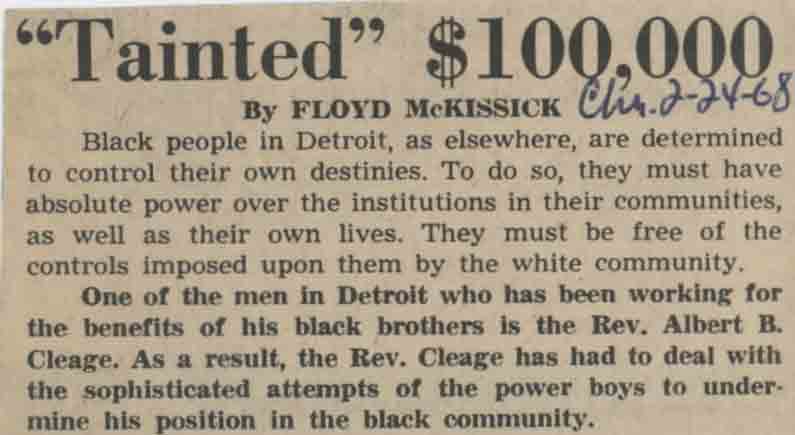

The FSD received $85,000 from Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization and $100,000 from the New Detroit Committee for its reconstruction plan. However, the money given to the FSD by the NDC stipulated that they could not participate in political activity so they turned the $100,000 down. In response, Joseph Hudson, chair of the NDC, requested a meeting with Karl Gregory who served as the liaison between the NDC and the FSD. From that meeting Karl Gregory developed a relationship with the NDC that allowed him to secure funding for the Inner City Business Improvement Forum and the CCAC housing reconstruction plan after the Federation for Self-Determination split in 1968.

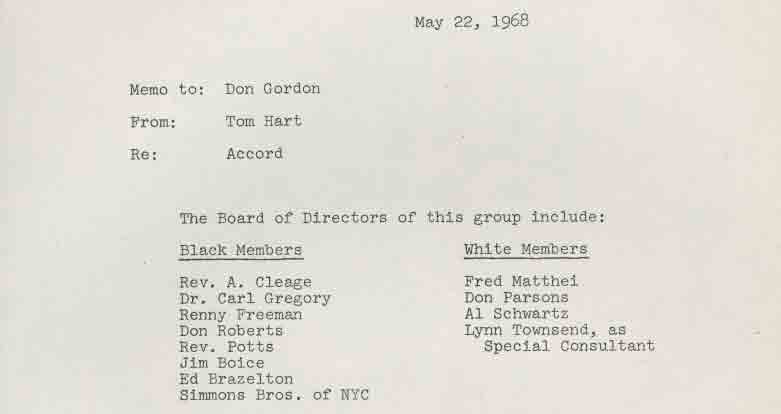

With help from the New Detroit Committee, Karl Gregory formed Accord, Inc in 1969 to implement the CCAC’s plan for housing reconstruction and Rev. Cleage served as a board member. Accord was a corporation organized to make a profit, and sought to do so by rehabilitating apartments with black contractors, organize tenants into cooperatives, and then transfer ownership to them.

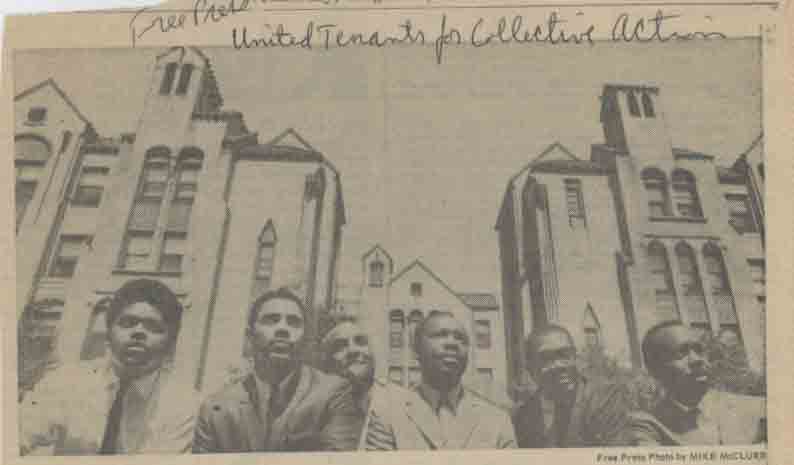

Another approach to community control of housing emerged from the work of Fred Lyles and United Tenants for Collective Action (UTCA). When Linden Management Company told tenants just a month after the Rebellion it was going to raise the rent for apartments in a building that badly needed a new furnace, roof, locks, plumbing, and electrical work, Fred Lyles organized a rent strike in the building. Calling themselves United Tenants for Collective Action, they protested the rent increase and demanded that Linden make needed repairs. Although Linden agreed to make the repairs, instead of actually making them they tried to evict Lyles. Represented in court by lawyers from Community Legal Services and Neighborhood legal Services, Lyles stayed in his apartment.

The publicity generated by Lyles court appearance and the successful rent strike made it possible for UTCA to expand their work. Partnering with the West Central Organization and the Trade Union Leadership Council, and receiving favorable coverage from the Michigan Chronicle and the Inner City Voice, within a year UTCA was successfully organizing tenants in multiple buildings. Once UTCA organized a building, they asked tenants if they wanted begin a rent strike. Most answered yes and UTCA supported tenants in navigating the legal process of withholding rent.

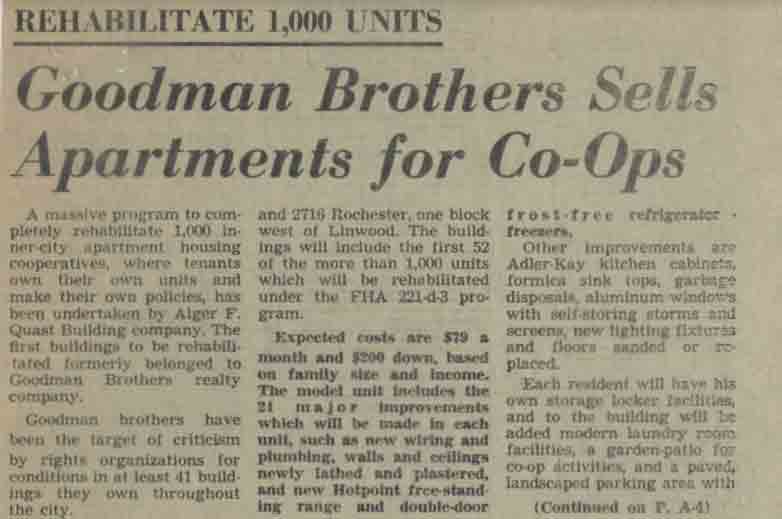

UTCAs rent strike strategy proved so successful that by spring 1968, they had formed six tenant’s councils, all in buildings owned by notorious slumlord, Goodman Brothers Management. When all six councils went on strike at the same time, it crippled Goodman Brothers, who initially responded by threatening the strikers and their leader. Not fazed by Goodman Brothers’ threats, Lyles and UTCA maintained their position throughout the summer while successfully organizing additional Goodman Brothers buildings.

In response to this growing pressure, Goodman Brothers offered to turn over control of seventeen buildings near Twelfth Street to United Tenants for Collective Action. While UTCA would not outright own the buildings, they would receive 75 percent of the rent and have the option to purchase them from Goodman Brothers outright. Seeing the turnover as an opportunity to provide decent housing to low-income blacks and to facilitate collective ownership and community control over housing, Lyles agreed to Goodman Brothers’ terms and the buildings were turned over to UTCA.

UTCA formed United Tenants for Collective Management (UTCM) to oversee the transition. Like Accord, Inc., UTCM sought to work only with black contractors and construction companies as a means to spur black economic development. Both UTCM and Accord, Inc. intended to hire Urban Design and Development Group (UDDG), a black owned architectural and design firm with links to NAACP tenant organizers. With these design plans, both organizations planned to contract black construction firms who would hire black workers from a newly formed black all trades union, United Construction Trades Local 124. After construction was finished, tenants organized into co-ops were to be put in charge of the management of buildings. As historian David Goldberg has pointed out, “this approach represented a coordinated attempt by Detroit’s Black power movement to secure jobs as well as local control of the post-rebellion rebuilding process.”

Despite this well conceived plan, within a few years both Accord, Inc., and UTCM were plagued with problems. The problems began when some white members of Detroit’s construction unions protested the use of workers from United Construction Trades Local 124 for rehabilitation projects, going so far as the completely sabotage one of Accord’s projects. Delaying construction by pouring cement into plumbing stacks, these white union members caused chaos throughout the whole chain of black owned businesses that were a part of the black power movement’s attempt to create community controlled housing. Within two years, Accord was bankrupt. UTCM met an equally unfortunate fate when Fred Lyles was shot and paralyzed, forcing a leadership change that was not equipped to principally deal with the kinds of problems that plagued Accord and within just a few years UTCM abandoned its goal of collective ownership and working with black contractors and subcontractors.

References

David Goldberg, “Community Control of Construction, Independent Unionism, and the ‘Short Black Power Movement in Detroit,” Black Power at Work: Community Control, Affirmative Action, and the Construction Industry, Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2010

In the wake of the Rebellion, Richard B. Henry and Henry L. King of the Malcolm X Society produced this proposal for a co-operative redevelopment plan in August 1967. —Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

The Inner-City Business Improvement Forum (ICBIF) was a non-profit organization dedicated to Black economic independence. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Press release announcing the formation of Accord, Inc., June 11, 1968. The release contains statements from Chairman Karl Gregory, along with information on the Board of Directors. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Statement from United Tenants for Collective Action on the origins, history, and actions of the organization, 1970. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

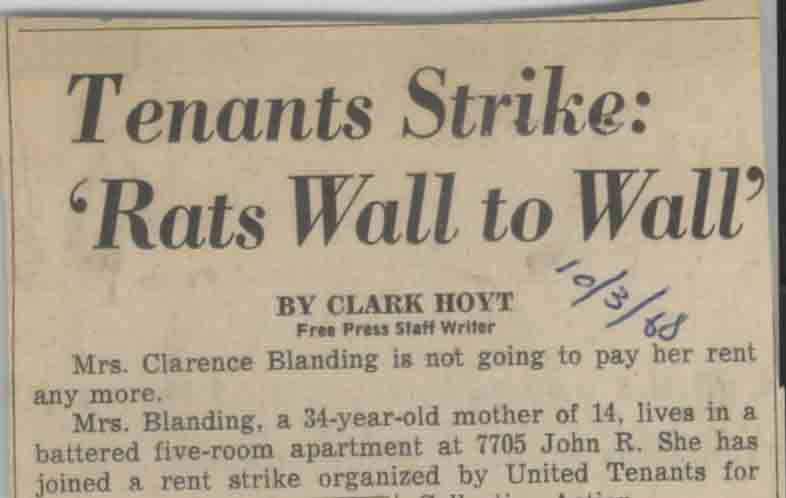

Detroit Free Press article by Clark Hoyt, October 3, 1968. \”Tenants Strike: \’Rats Wall to Wall.\’\” Tenants in 15 buildings went on strike, refusing to pay rent for apartments with unfit living conditions. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Published as \”the voice of Detroit\’s Black revolution,\” Sauti included stories on union movements, government spending and poverty, and anti-Vietnam war effort. This edition includes coverage of the sabotage of UCT Local 124. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Explore The Archives

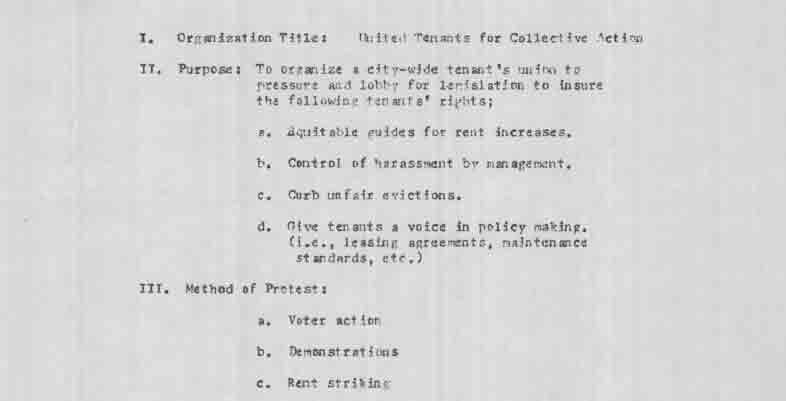

Statement issued by the UTCA outlining the organization\’s purpose, methods of protest, and organizational structure. The document offers important insight into the structure, ideologies, and visions for the organization. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

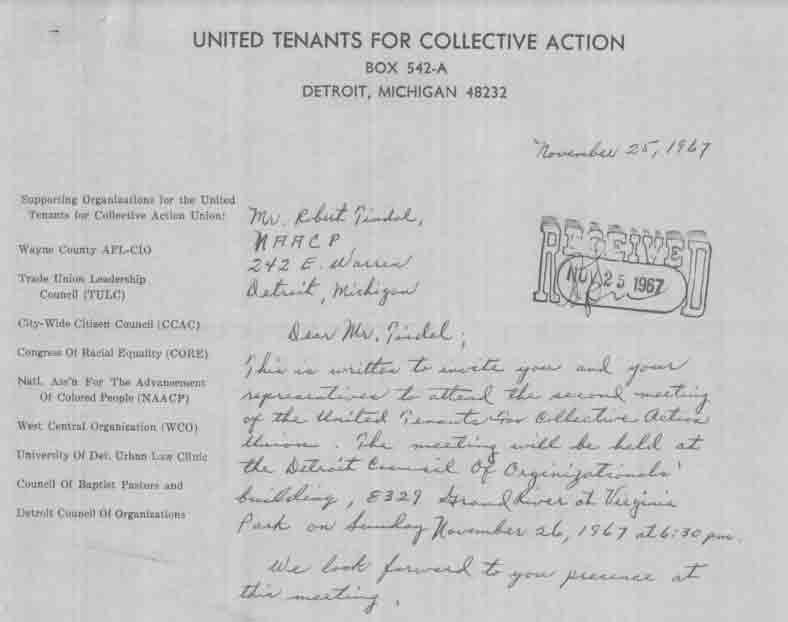

Letter from UTCA Chairman Fred Lyles to Robert Tindal of the Detroit NAACP, November 25, 1967. The letter was an invitation for Tindal to attend the second meeting of the UTCA, and the letterhead indicates various organizations in Detroit that supported the UTCA. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Statement from UTCA president Kenneth Sledge on the United Tenants Rehabilitation Co. Inc. The statement illustrates demands for community control of housing and redevelopment in Detroit following the 1967 Rebellion. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Clipping, \”\’Tainted\’ $100,000\” (February 24, 1968). The Rev. Albert B. Cleage turned down the offer of $100,000 from the newly-created New Detroit Committee, citing restrictive conditions. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Memo from Tom Hart to Don Gordon on Accord, Inc.\’s Board of Directors, May 22, 1968. The memo reflects racial and personal tensions over leadership and control of the organization. –Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.